With our free press under threat and federal funding for public media gone, your support matters more than ever. Help keep the LAist newsroom strong, become a monthly member or increase your support today.

Black History Month May Be Over But Sharing Black Stories Is Still A Priority

Our news is free on LAist. To make sure you get our coverage: Sign up for our daily newsletters. To support our non-profit public service journalism: Donate Now.

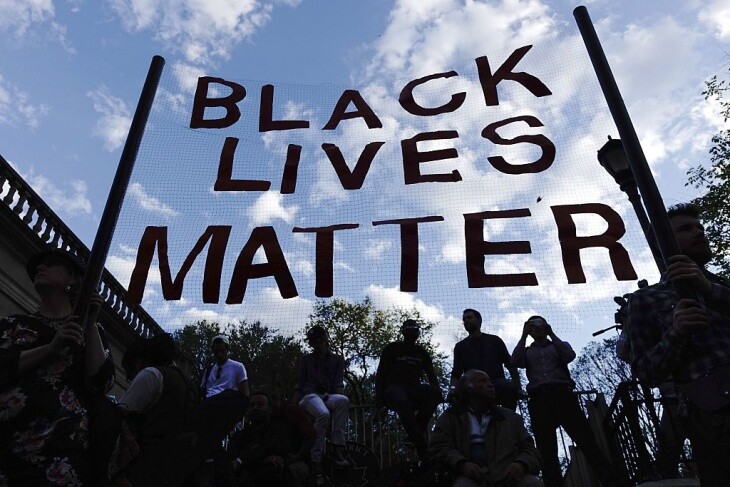

During February, LAist celebrated Black History Month by centering around one question: What does it mean to be Black in L.A? A seemingly simple question, the experiences and stories we shared from BIPOC readers and our colleagues illustrated how society's seismic shift in how we think and talk about race and race-related issues complicates this narrative.

We heard from Black Angelenos from across the city. Some have always called L.A. home while others are recent arrivals. We also continued posting our Racism 101 panelists' responses to questions we received about everything from cultural appropriation to how to show solidarity for BIPOC friends without overwhelming, or even, irritating them. February's Race In LA essayists were all strong Black voices who spoke to a spectrum of experiences, from the police to the pandemic.

We all remember 2020 as a difficult year. The deaths of Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, George Floyd and more sparked protests and tough conversations around race-related issues. While these events heavily influenced how we approached our Black History Month coverage this year, it wasn't our impetus to shift additional editorial focus on Black voices. This work, and our increased transparency in how we cover the Black community pre-dates last summer's unrest.

In 2019, we began planning to launch The 8 Percent on LAist to create an opportunity to go deeper and explore the inextricable ties between L.A. and its Black residents.

An extension of our Race In LA series, The 8 Percent was the springboard for our Black History Month coverage. In all of this content, several themes emerged.

BLACK IDENTITY

Most submissions for On Being Black In LA involved some aspect of one's identity as a Black person. One woman who grew up in the San Fernando Valley said when she was with kids at her Catholic prep school she felt like one person. During summer visits with her dad in inner city St. Louis, she felt like she had to be a different person around neighborhood kids. Code switching became her survival mechanism.

A man who grew up in neighborhoods across the city said he struggled with trying to "fit in a racial box" being too white for the Black kids and too Black for the white kids, all while being viewed as a threat and gang member (though he was neither) by police.

"Being Black in L.A. means I'm part of the 8% of Black people who are still here, fighting for the space that was once a place of refuge for my relatives and ancestors, that became a place that not only terrorized me, but taught me to love who I am, be proud of where I'm from and, ultimately, how to find success in city where it's tough to just survive, let alone thrive. It's a gift and a curse, but what is life without duality?"

Our own reporter, Emily Elena Dugdale, shared what it's like to be Afro Colombian in L.A., which she said largely centers the Latinx experience around Mexican American culture. She explained that there's "so little recognition of the thousands of dark-skinned, Black Latinx folks who are essential to the fabric of this place" and that it makes her feel like she has to "'choose' to fit in a racial box" in one of the world's most diverse cities.

MORE FROM RACE IN LA:

- The 8 Percent: Exploring The Inextricable Ties Between L.A. And Its Black Residents

- Racism 101 on Take Two: How to Be an Ally, Code Switching for Survival, Deconstructing 'Defund the Police', Legacy of Slavery

One woman found it difficult to fit in as both Black and white growing up. She saw few families that looked like hers, and when she did, she felt "at ease." So, she wrote a children's book to help kids today navigate what it means to be biracial.

A Race In LA essayist wrote about her amusing but at times, horrifying experiences with strangers' questions about her appearance. Her mother is white and her father is Black, but she said she people have assumed she was "white, Black, Asian, Hawaiian, Brazilian, French, Mexican, Belizean, Jewish, Moroccan, and many more."

"Whenever I was asked, 'Are you adopted?' or 'Where do you get your color?' or 'What are you?' or 'Where are you from?' I had no idea what people were getting at. So I tended to answer literally, without elaborating, as in 'from here,' which was not the answer people were looking for."

BLACK SPACES & COMMUNITY

We shared uplifting stories about Black people who carved out spaces for themselves in the face of oppression and resistance. That's the story of the gems of South Central's jazz scenein the 1930s and '40s, the Dunbar Hotel and Club Alabam. These establishments helped make South Central, already the epicenter of L.A.'s Black community, the heart of jazz on the West Coast.

Similarly, one of the most heartbreaking stories we shared was from our colleague Velincia Ellis, a longtime financial analyst in our public media organization. She wrote about gentrification's slow creep into her South L.A. neighborhood. "I see older Blacks losing their homes to death or foreclosure and resold to non-Blacks," she said. "And, I wonder: What happened? Where did my people go?"

ANTI-BLACK RACISM

We also took a step back to explore wider issues. Race In LA contributor Brandi Carter examined how today's wealth gap between Black Americans and other racial groups was exacerbated by slavery's legacy. She took a modern view of the broken promise of 40 acres and a mule.We also answered a Racism 101 inquiry, "When will we stop portraying racism as something that primarily happens between white and Black people?" We used Carter's research on reparations to explain how biased legislation like the New Deal and GI Bill helped white people stay ahead of Black people. Our panelists had a lot to unpack.

We heard feelings of overt, explicit bouts of discrimination, marginalization, isolation and racism. Two Racism 101 panelists discussed what it means to move past the "angry Black woman" stereotype and call out tone policing. An ER nurse who has been working on the frontlines of COVID-19 since the pandemic began wrote a wrenching account of having to separate her racial identity from her work in order to cope. As she explained, "It was easier to find solace in my job, easier to be just a nurse, than to be a Black nurse." One man from Long Beach even described his life in L.A. as a "slow burn of anti-Blackness."

We know there's more work to do to continue to hear voices that for too long didn't have a place in many mainstream media organizations.

We want to make sure we honor this comment from a listener and reader about producer Olivia Riçhard's report on April Reign and her #OscarsSoWhite legacy. This new donor told us:

"I have been listening for more than 20 years, but it wasn't until now that I ever felt the need to write a notification. I have been very impressed with KPCC improving reporting on Black communities. So often it feels tokenized or that trauma is the only thing that gets attention or highlighted. I wanted to congratulate you how you chose to handle the current lack of diversity in Hollywood, especially with the confrontation the Golden Globes are having with their lack of representation. It felt timely, imported and nuanced."

HELP US CONTINUE TO TELL BLACK STORIES

At LAist, we believe in journalism without censorship and the right of a free press to speak truth to those in power. Our hard-hitting watchdog reporting on local government, climate, and the ongoing housing and homelessness crisis is trustworthy, independent and freely accessible to everyone thanks to the support of readers like you.

But the game has changed: Congress voted to eliminate funding for public media across the country. Here at LAist that means a loss of $1.7 million in our budget every year. We want to assure you that despite growing threats to free press and free speech, LAist will remain a voice you know and trust. Speaking frankly, the amount of reader support we receive will help determine how strong of a newsroom we are going forward to cover the important news in our community.

We’re asking you to stand up for independent reporting that will not be silenced. With more individuals like you supporting this public service, we can continue to provide essential coverage for Southern Californians that you can’t find anywhere else. Become a monthly member today to help sustain this mission.

Thank you for your generous support and belief in the value of independent news.

-

What do stairs have to do with California’s housing crisis? More than you might think, says this Culver City councilmember.

-

Yes, it's controversial, but let me explain.

-

Doctors say administrator directives allow immigration agents to interfere in medical decisions and compromise medical care.

-

The Palisades Fire erupted on Jan. 7 and went on to kill 12 people and destroy more than 6,800 homes and buildings.

-

People moving to Los Angeles are regularly baffled by the region’s refrigerator-less apartments. They’ll soon be a thing of the past.

-

Experts say students shouldn't readily forgo federal aid. But a California-only program may be a good alternative in some cases.