This story is free to read because readers choose to support LAist. If you find value in independent local reporting, make a donation to power our newsroom today.

For the first time, you can look up serious use of force and police misconduct incidents in California.

LAist, KQED and other California newsrooms, together with police accountability advocates, have published a database that houses thousands of once-confidential records gathered from the state’s nearly 700 law enforcement and oversight agencies.

- Jump straight to: How to use the police records database yourself

The free database, first published last week, has been in the works for seven years. It contains files for almost 12,000 cases, promises to give anyone — including attorneys, victims of police violence, journalists and law enforcement hiring officials — insight into police shootings and officers’ past behavior. LAist is making if available to readers on on website now.

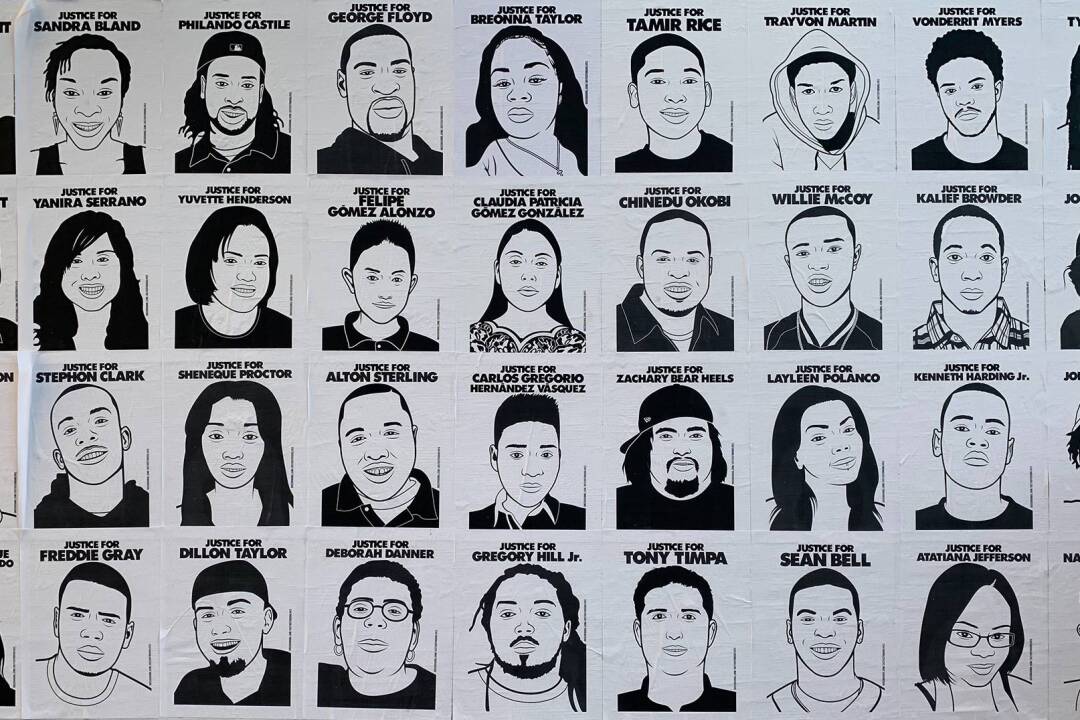

Cephus Johnson, whose nephew Oscar Grant was fatally shot in the back by a BART police officer in Oakland in the early morning hours of Jan. 1, 2009, knows firsthand just how important this database will be to other families who’ve lost people to police violence.

“ For impacted families, the first question is: ‘What happened?’” he said.

They can now find details of what happened to their loved ones and how the police investigated it — or what they overlooked — without having to deal with the often frustrating process of trying to obtain the records themselves.

Getting those answers, Johnson said, “is the beginning of part of the healing process.”

Click here to search the database.

Shedding light on secret records

For decades, misconduct and use-of-force records for California law enforcement officers were among the most difficult to obtain. That began to change in 2018 with the passage of Senate Bill 1421, the “Right to Know” Act, which came about with the help of Johnson and other police accountability advocates.

The law unsealed records for incidents in which officers fired a gun or used force resulting in serious injury or death, and for officers who were found to have been dishonest or committed sexual assault. In 2021, the passage of another bill expanded the law to include cases of officer discrimination, excessive force and wrongful arrests or searches.

But the new laws were just the beginning of the fight to pry open the black box of police accountability — which continues today. Agencies often slow-walk or refuse to provide records, and have even destroyed them. LAist, KQED and other outlets have sued multiple agencies, including the state attorney general, in order to force compliance.

Faced with these obstacles — and the difficulty of navigating California’s disparate law enforcement agencies, including 58 sheriff’s departments, hundreds of police departments, transit authorities and the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation — LAist co-founded The California Reporting Project, a collaborative of more than 30 news outlets which is now led by Big Local News at Stanford University, the UC Berkeley Investigative Reporting Program and the Berkeley Institute of Data Science.

“We knew from the start that this information needed to be available to the public,” KQED Editor-in-Chief Ethan Toven-Lindsey said. “Police misconduct records shouldn’t be locked away in filing cabinets where only a few people can see them.”

Eventually, The California Reporting Project joined forces with the Police Records Access Project, a transparency coalition which includes the ACLU, the Innocence Project, Stanford and UC Berkeley. In 2023, Gov. Gavin Newsom allocated $6.7 million for the effort.

Jumana Musa, director of the Fourth Amendment Center at the National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers (NACDL), said her organization joined the collaborative because justice requires transparency.

“This information gets hidden, it gets buried, it is not accessible,” she said. While Musa will use the database to help defend her clients, she said there’s an even more acute need for law enforcement agencies get familiar with the tool: “to ensure that you’re not gonna hire people and give them a weapon and give them a badge when that person has been known to be problematic [or] dangerous.”

The California Police Chiefs Association did not respond to request for comment.

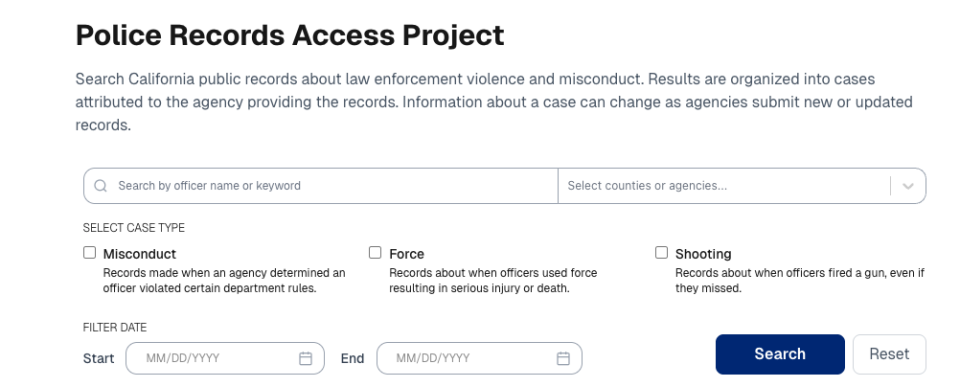

How can I use the database?

The nearly 12,000 cases make up about 1.5 million pages at the time of publication — but there are several ways to search and use the database.

Three categories divide the cases: use of force, shootings and misconduct. There is a range of document types, from investigative reports to interview transcripts and incident summaries.

There is no cost for using the tool, and you won’t be asked to provide any information to search these records.

Lisa Pickoff-White, co-founder and research director of The California Reporting Project, said it’s helpful to take some time to understand the kinds of cases and records in the database before drawing any conclusions.

You can do keyword searches, filter your search by date or the agency that provided the records — for example, the Los Angeles County Sheriff, the Los Angeles Police Department.

Pickoff-White suggests starting simply. “Search for things like ‘taser’ or ‘canine.’ Or search for an officer’s name. Then review the records to see if you’ve found cases where they used force or violated policy.” But remember: just because an officer’s name is in the database, it doesn’t necessarily mean they were involved in misconduct or use of force.

The “About” page explains the type of records, methodology and the limitations of the database. If you find information in the database that you don’t think should be public, you can also submit a request to remove it.

Keep in mind this database is a living thing and is far from complete — the people maintaining it are adding new records as they receive them.

Who is this database for?

Victims of police violence and their families

The records in the database, Cephus Johnson said, can give families like his who have experienced police violence a clearer picture of what took place, and help them “determine how they will get justice for their loved one.”

But Johnson advises families to use the tool with a great deal of care because sometimes the records can contain examples of callous police behavior, negligence or descriptions of graphic injuries.

“On top of the mourning, you’re angry, you got many emotions that you gotta really deal with,” he said.

Johnson suggests that certain family members — say, the grieving mother of someone killed by police — might be better served if a relative or friend reviews the records.

“There’s got to be some caretaking,” he said, “because we know sometimes you’re gonna hear things that you just can’t believe these officers would do.”

Researchers

“This kind of data is necessary for even basic forms of independent oversight,” said Tarak Shah, a data scientist who helped manage the Police Records Access Project.

Shah said he’s excited about the database’s potential to contribute to criminal justice research. He’s spoken to researchers interested in how police killings get classified by independent medical examiners vs. coroners, who are under the purview of the local sheriff.

“As a researcher, you might have questions about whether it’s possible to do unbiased investigations in those scenarios,” he said. Those cause-of-death determinations can mean the difference between a criminal investigation of a law enforcement officer and a death essentially going unexamined.

Other research areas could include the intersection of mental health and law enforcement, the role drug and alcohol impairment can play in some police encounters and a better understanding of what consequences officers face for misconduct — ranging from casual misogyny and racism to excessive force.

Shah said the depth and complexity of the investigative files have been both the “strength and the main challenge of this project.” The database contains incredibly granular information about officer behaviors and key incidents, but the records are not neatly organized into structured data like you might see in a spreadsheet.

He said the database would not be possible without the latest advancements in AI and large language models, which they used to help categorize and sort the records, and to identify and redact sensitive information.

Lawyers

Police officers’ credibility is fundamental to the criminal justice system; when officers take the stand, their word often determines the outcome of a case. Attorneys can now look up officers who’ve been dishonest or biased — key information for juries assessing the truth of their testimony.

“To me, the primary use is to impeach officers on the stand or to be able to properly defend the client, with full knowledge of who it [is] they’re dealing with,” said Musa, the attorney with NACDL.

In 2019, in one of the first cases unsealed by the new transparency law, KQED uncovered the story of a Rio Vista police officer who had lied on official documents. As a result, the Solano County District Attorney dropped criminal charges against a woman who a police dog had mauled.

Civil rights attorneys who often look for evidence of patterns and practices within departments to substantiate their clients’ claims could also find useful information in the database.

Journalists

“The one thing that moves the needle when it comes to getting accountability in the criminal legal system is investigative journalism,” said Barry Scheck, co-founder of the Innocence Project. “If you can expose people that are systematically breaking the law or not playing by the rules or harming people they should be protecting — when you get those stories, that’s when things change.”

An LAist investigation last year reported that nearly a third of LAPD shootings since 2017 involved a person in a mental health crisis, despite years of promises that the department was working to deescalate those encounters.

Around the state, members of the collaborative:

- Succeeded in forcing the city of Richmond to release records revealing 73 police dog bites

- Identified 70 Los Angeles Sheriff’s deputies with a range of previously undisclosed transgressions on their records

- Unveiled records that showed how a Sutter County sheriff’s deputy used his position to coerce women into having sex with him on duty.

Taken together, press coverage has helped move the needle on police reform in California. In 2020, state lawmakers passed a law requiring the state attorney general to investigate all police shootings in which the subject was not armed.

In 2022, they passed a police decertification law, putting in place a mechanism to strip officers who’ve committed egregious misconduct of their badges. This year, the Legislature is considering a number of additional transparency and oversight measures.

Have you found this database useful?

We want to hear who you are, how you’re using this database and why. Please tell us a bit about yourself, your work and what brought you to the database.