With our free press under threat and federal funding for public media gone, your support matters more than ever. Help keep the LAist newsroom strong, become a monthly member or increase your support today.

LA's Special Education Teachers Are Speaking Out About Contract Shortcomings

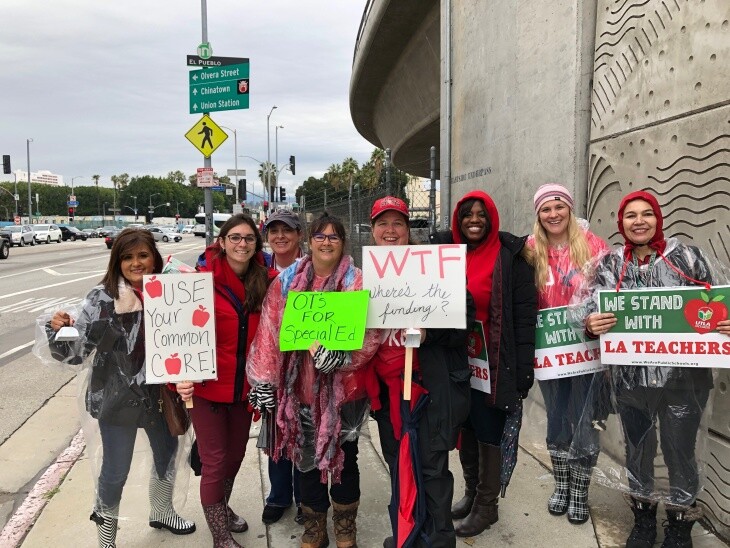

Eighty-one percent of Los Angeles teachers voted for the contract that ended their strike earlier this month. But there's still a lot of concern coming from one group: special-ed teachers.

They say sections of the L.A. Unified School District contract related to their needs --and, by extension, the needs of their students -- haven't been significantly changed in decades.

One major issue is class size, which didn't budge for special-ed classrooms during the recent negotiations.

"VOTING NO!!," one teacher posted on Facebook last week. "The SPED protocols are virtually unchanged!! Many of these teachers are taking to social media to voice concerns.

Amber Schwindler teaches a special education class for autistic students at Germaine Street Elementary School in the San Fernando Valley.

She met with LAist after a long school day this week. To demonstrate one of the many challenges of her job, she pulled out a laminated math worksheet she'd made using velcro numbers and the equation two plus zero. It might look like a simple addition equation, she said, but for her students, it's not.

"Every kid has an individualized need... there's 17 steps in order to tie your shoe... and people don't think of this task analysis... That's a lot for 10 kids."

"It's also a lot of occupational therapy," she said. "Because to un-velcro and to velcro the pieces is hard for some of our kids -- to scan, find the right number is hard. When I say we're doing addition,we're doing addition, and OT, and speech, and everything -- all at one time."

Roughly 73,000 LAUSD students are served in special education, making the district one of the highest special education populations in the country. According to LAUSD, it spent an average of $20,689 dollars per special-ed student last year; that's about $8,000 more per pupil compared to general education students.

But to teachers who are unhappy with the new contract, the extra money doesn't mean much if class sizes remain too big.

If you think teaching a larger-than-average general-population class is difficult, Schwindler said, imagine how difficult it must be in a special-ed setting, where even tasks some might say are simple become complicated.

"Every kid has an individualized need," she said. For example, "there's 17 steps in order to tie your shoe. First, you have to put your sock on, then you put your shoe on, then you have to loosen it... and people don't think of this task analysis all the time."

Planning for every action item, every schedule change, every transition, every student at every part of the day, she added -- "That's a lot for 10 kids."

While a class of 10 might sound reasonable, she said, it can quickly become unmanageable.

And Schwindler's frustration is that not much has changed for these students in nearly four decades.

The shortage of knowledge, she explained, meant solutions were tough to agree on.As Gloria Martinez, elementary vice president of the teacher's union, told LAist, "It's astounding." Garcia said part of the problem is a lack of accurate data. No one knows exactly what's going on in special-ed classrooms.

"We couldn't start negotiating class size numbers with numbers that we weren't sure of ourselves," she said. "There were some schools that were reporting a 400 percent student special-ed population. That's not possible."

Even though special-ed class sizes was difficult to negotiate on, there was a bright spot: the new contract calls for a joint task force to study teacher caseloads to improve the results of the next bargaining session.

"For the last 37 years we didn't have a starting point," she said. "At least now, the information that we get will be more regular and consistent."

The new contract states that special-ed class size could grow to as many as 12 students, in which case the district, knowing that it's pushed the envelope, is required to remedy the situation.

One potential remedy is to add extra adult supervisors, but Schwindler doesn't see that as a solution.

"Okay, well, now I have 12 kids, and I have five adults that I have to manage," she explains. "So really, that's 17 bodies, that's 17 personalities. It's no longer a small learning environment."

LAUSD declined our interview request, but sent a statement explaining that the new contract stipulates the creation of a committee to study the workloads and caseloads of special-education teachers and explore ways to make assignments more equitable. The committee will also make recommendations for ensuring that students receive appropriate services and provide strategies to better integrate students with disabilities into the general education classroom.

The statement also notes that LAUSD remains committed to pursuing additional funding so that more options become available to special-education teachers.

The district already secured a five-year, $5 million grant that will help Los Angeles Unified recruit credentialed special-education teachers that they say will continue to support students with special needs.

For teachers like Schwindler, that funding can't come soon enough.

At LAist, we believe in journalism without censorship and the right of a free press to speak truth to those in power. Our hard-hitting watchdog reporting on local government, climate, and the ongoing housing and homelessness crisis is trustworthy, independent and freely accessible to everyone thanks to the support of readers like you.

But the game has changed: Congress voted to eliminate funding for public media across the country. Here at LAist that means a loss of $1.7 million in our budget every year. We want to assure you that despite growing threats to free press and free speech, LAist will remain a voice you know and trust. Speaking frankly, the amount of reader support we receive will help determine how strong of a newsroom we are going forward to cover the important news in our community.

We’re asking you to stand up for independent reporting that will not be silenced. With more individuals like you supporting this public service, we can continue to provide essential coverage for Southern Californians that you can’t find anywhere else. Become a monthly member today to help sustain this mission.

Thank you for your generous support and belief in the value of independent news.

-

What do stairs have to do with California’s housing crisis? More than you might think, says this Culver City councilmember.

-

Yes, it's controversial, but let me explain.

-

Doctors say administrator directives allow immigration agents to interfere in medical decisions and compromise medical care.

-

The Palisades Fire erupted on Jan. 7 and went on to kill 12 people and destroy more than 6,800 homes and buildings.

-

People moving to Los Angeles are regularly baffled by the region’s refrigerator-less apartments. They’ll soon be a thing of the past.

-

Experts say students shouldn't readily forgo federal aid. But a California-only program may be a good alternative in some cases.