This story is free to read because readers choose to support LAist. If you find value in independent local reporting, make a donation to power our newsroom today.

This archival content was originally written for and published on KPCC.org. Keep in mind that links and images may no longer work — and references may be outdated.

Remembering Dodger Stadium when it was Chavez Ravine

As the Dodgers gear up for Game 6 of the World Series — once again, on their home turf — it's worth remembering that before Dodger Stadium was a legendary baseball venue, it was known as Chavez Ravine.

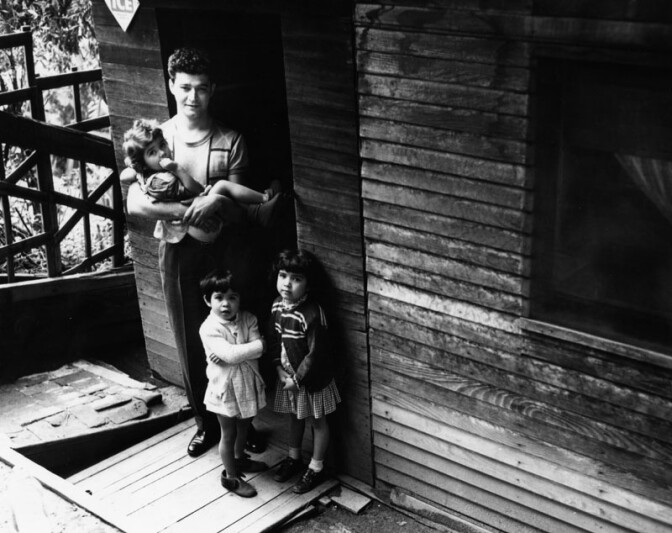

The area was home to generations of families, most of them Mexican-American.

After the Dodgers made the deal to ditch Brooklyn, Los Angeles officials used eminent domain and other political machinations to wrest that land away from its owners.

It was ugly. It was violent. It remains the sort of living history that residents of a city don't like to remember.

Chavez Ravine was named after Julian Chavez, a rancher who served as assistant mayor, city councilman and, eventually, as one of L.A. County's first supervisors. In 1844, he started buying up land in what was known as the Stone Quarry Hills, an area with several separate ravines. Chavez died of a heart attack in 1879, at the age of 69.

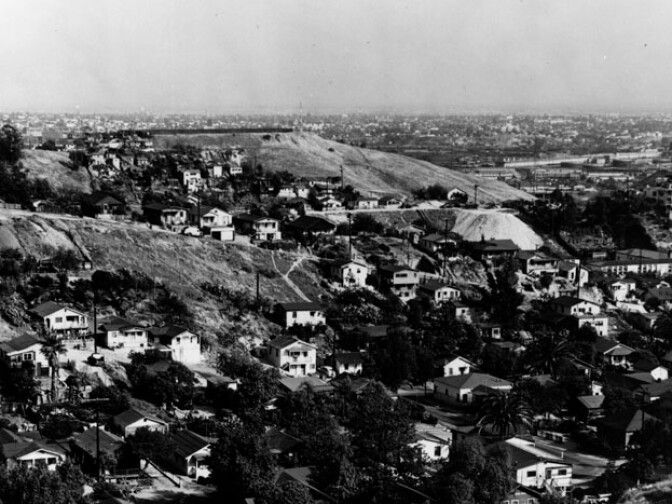

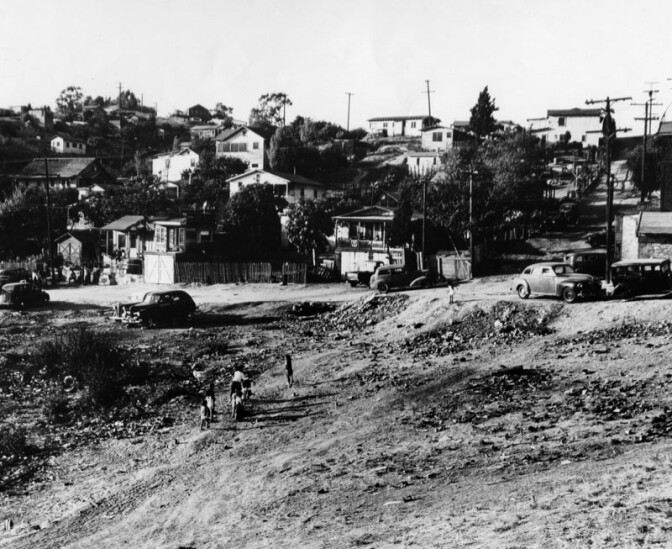

By the early 1900s, semi-rural communities had sprung up on the steep terrain, mostly on the ridges between the neighboring Sulfur and Cemetery ravines.

What eventually came to be called Chavez Ravine encompassed about 315 acres and had three main neighborhoods — Palo Verde, La Loma and Bishop.

It had its own grocery store, church and elementary school. Many residents grew their own food and raised animals such as pigs, goats and turkeys.

Many Mexican-American families, red-lined and prevented from moving into other neighborhoods, established themselves in Chavez Ravine.

Residents of the tight-knit community often left their doors unlocked.

Outsiders often saw the neighborhood as a slum. City officials decided that Chavez Ravine was under-utilized and ripe for redevelopment, kicking off a decade-long battle over the land.

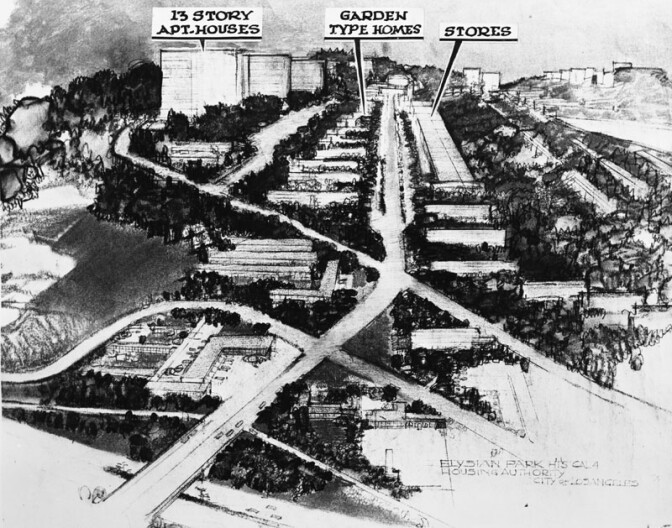

They labeled it "blighted" and came up with a plan for a massive public housing project, known as Elysian Park Heights.

Designed by architects Robert E. Alexander and Richard Neutra and funded in part by federal money, the project would include more than 1,000 units — two dozen 13-story buildings and 160 two-story townhouses — as well as several new schools and playgrounds.

In the early 1950s, the city began trying to convince Chavez Ravine homeowners to sell. Many residents resisted, despite intense pressure.

Developers offered immediate cash payments to residents for their homes. Remaining homeowners were offered less money, worrying residents that they wouldn't get a fair price if they held out.

In other cases, officials used the power of eminent domain to acquire plots of land and force residents out of their homes. When they did, they typically lowballed homeowners, offering them far less money than their properties were worth.

Chavez Ravine residents were also told that the land would be used for public housing and those who were displaced could return to live in the housing projects.

One way or another, by choice or by force, most residents of the three neighborhoods ended up leaving Chavez Ravine by 1953, when the Elysian Park Heights project fell apart.

The city's new mayor, Norris Poulson, opposed public housing as "un-American," as did many business leaders who wanted the land for private development.

The city of Los Angeles bought back the land, at a much lower price, from the Federal Housing Authority — with the agreement that the city would use it for a public purpose.

By 1957, the area was a ghost town. Only 20 families, holdouts who had fought the city's offers to buy and reclaim their land, were still living in Chavez Ravine.

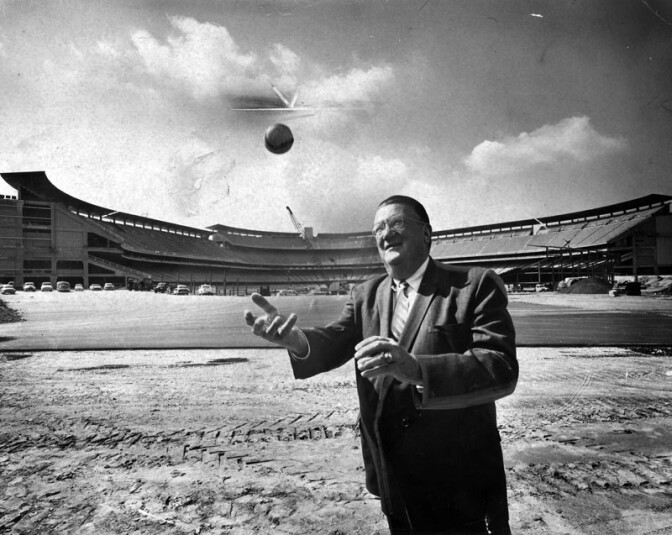

In June of 1958, voters approved (by a slim, 3 percent margin) a referendum to trade 352 acres of land at Chavez Ravine to the owner of the Brooklyn Dodgers, Walter O'Malley.

The following year, the city began clearing the land for the stadium.

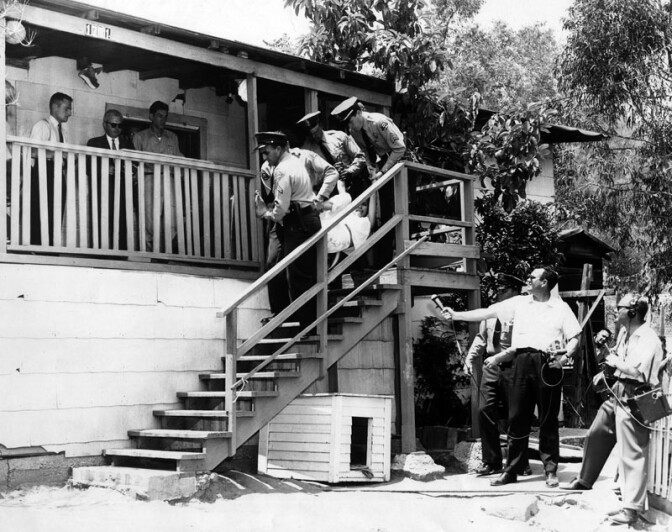

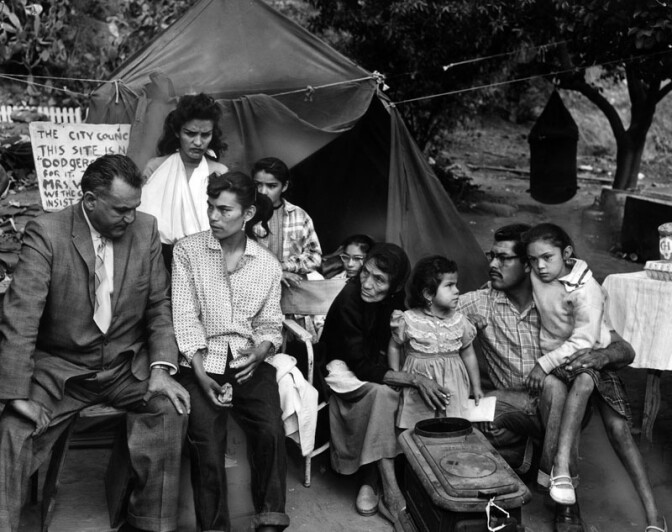

On Friday, May 9, 1959, bulldozers and sheriff's deputies showed up to forcibly evict the last few families in Chavez Ravine. Residents of the area called it Black Friday.

Sheriff's deputies kicked down the door of the Arechiga family home. Movers hauled out the family's furniture. The residents were forcibly escorted out. Aurora Vargas, 36, was carried, kicking and screaming, from her home at 1771 Malvina Ave. by four deputies. Minutes later, her home was bulldozed.

Crews eventually knocked down the ridge separating the Sulfur and Cemetery ravines and filled them in, burying Palo Verde Elementary School in the process.

The Arechiga family, led by 66-year-old matriarch Avrana Arechiga, camped amid the rubble for the next week before finally giving up.

Crews broke ground for Dodger Stadium four months later, on September 17, 1959. While it was being built, the Dodgers played games at the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum.

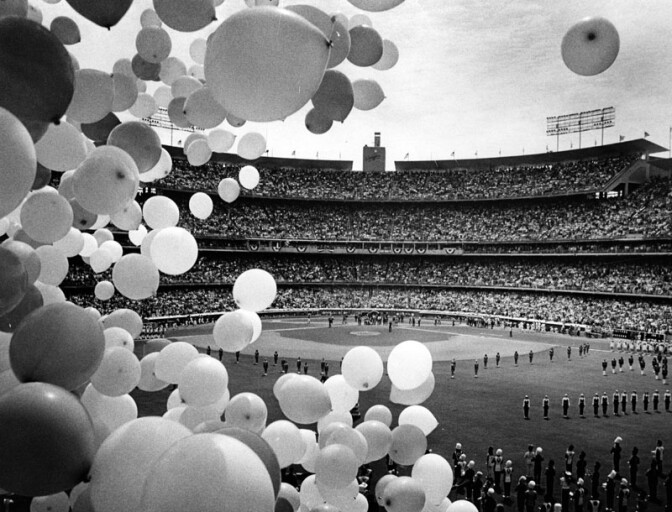

The 56,000-seat Dodger Stadium opened on April 10, 1962, on a site that thousands of people had once called home.

It is currently the third oldest major league ballpark still in use, after Fenway Park and Wrigley Field.

![May 8, 1959: "Several Chavez Ravine residents fought eviction, including Aurora Vargas, who vowed that, 'they'll have to carry me [out].' L.A. County Sheriffs forcibly remove Vargas from her home. Bulldozers then knocked over the few remaining dwellings. Four months later, ground-breaking for Dodger Stadium began." Courtesy of the Los Angeles Public Library](https://scpr.brightspotcdn.com/dims4/default/890c619/2147483647/strip/true/crop/800x600+0+10/resize/672x504!/quality/90/?url=https%3A%2F%2Fa.scpr.org%2F175797_4ab7db7f5a4d81501331cf4b3d004132_original.jpg)