This story is free to read because readers choose to support LAist. If you find value in independent local reporting, make a donation to power our newsroom today.

Oil Spill Unravels Future Of Net-Making In Gulf

Just about every shrimp, fish or crab coming in off the Gulf of Mexico is caught in one of the green and white nets that hang on the local boats. But the boats -- and the nets -- along Louisiana's coast and in its bayous aren't seeing much action these days.

For the last remaining net maker in St. Bernard Parish, Erwin Menesses Jr., that's meant a 95 percent drop in business.

"My nickname is Bubba, and I make nets for a living," he says. "Trawl nets, crawfish nets, any kind of net you can imagine. And I enjoy it."

Here, fishing is woven into the Louisiana lifestyle as tightly as a knot in one of his nets. For at least 200 years, Menesses says, his family has passed down the art of net-making.

The Soul Of Freedom

Though the craft Menesses practices is now rare, the story of his business is not. Here, cottage industries like his have thrived. Many are small, often family-owned operations whose fates are tied to the fishing industry. All of those businesses are now in peril because of the oil spill, but Menesses says he can imagine no better job.

"Once you're a fisherman, it's kinda in your soul and a lot of people can't get rid of it. What gets in your soul? Freedom. You're free," Menesses says.

When asked if he has his freedom now, Menesses responds, "No, I lost it already, 'cause I'm already working for BP."

These days, he wears life jackets and steel-toe boots, and is regularly subjected to drug tests. And he says that's not part of normal life here. Like many fishing industry workers, he's repurposed himself for clean-up efforts. Now he's using his net-making skills to make pompoms -- like the ones cheerleaders use -- that help detect incoming oil.

"Some of the other fisherman take them out to Chandeleur Island and put 'em out on the line to test for oil coming in. And today they found some. And it's not going to be good. And it's -- it's awful," Menesses says.

'Katrina Knocked Us Down. The Oil May Knock Us Out'

Beneath the charming exterior, emotion runs raw for Menesses. And it's no wonder. Marshland butts up a mere quarter-mile from his home. So does a levee just down the street. Flooding from Hurricane Katrina chased him and the other net makers out of the parish. Menesses and his family moved to Texas for a while, but were drawn back to be back on the water. He returned and rebuilt this house, tile by tile.

The storm and floods tore off his back-porch workspace, so now he works indoors. Menesses says much of the fishing business -- including his -- can't file a claim for lost business because they don't keep records of their income.

"My business is a cash business, so I have no claim. So BP's actually gonna skate by and not have to pay for it," he says.

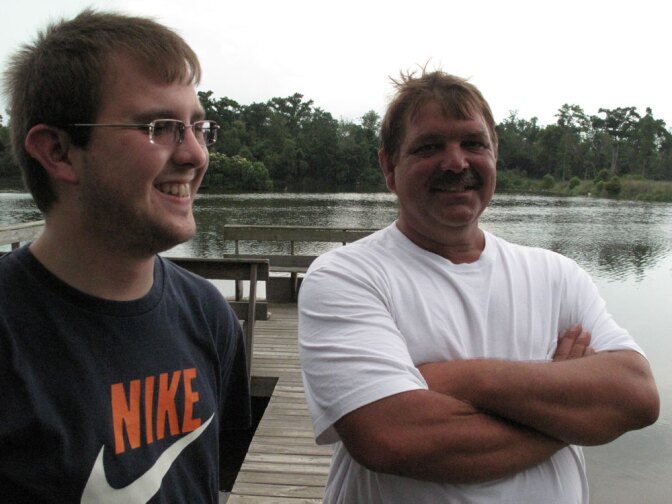

Now, he's torn about whether his 18-year-old son, Erwin III -- also known as Trey -- should take up net-making.

"Katrina knocked us down. The oil may knock us out. I don't even know if I would want my son living here, once the oil gets here. The smell ... the oil smells so bad that a chemical taste gets in your mouth and you can't wash it out with water," Menesses says.

Trey Menesses says the oil has made him unsure of the future of net-making. He plans to study business at the University of New Orleans in the fall.

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDA1OTI3MjQ5MDEyODUwMTE2MzM1YzNmZA004))