This story is free to read because readers choose to support LAist. If you find value in independent local reporting, make a donation to power our newsroom today.

Some Of California Is Free Of Drought, But The Climate Crisis Is Changing What That Means

The wet winter this year has many of us asking: Is California out of the drought? If only the answer were a simple yes or no — but drought, of course, is more complicated than that. Let’s dig into it.

The current state of drought

The rain and snowstorms we’ve had since late December have made a significant dent in California’s current drought, which has spanned the last three years and been the driest period in more than 100 years.

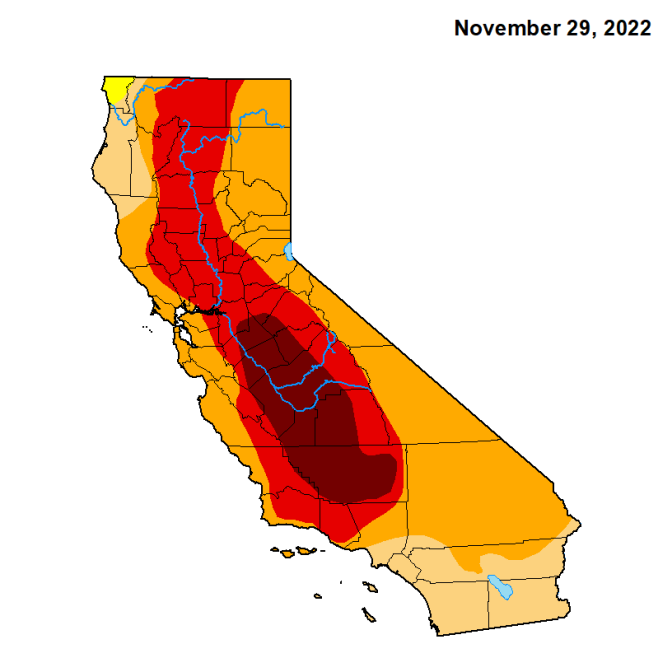

The latest data from the U.S. Drought Monitor show that recent storms have freed 17% of the state from drought conditions, with the biggest areas of improvement being the Sierra Nevada, central coast and far northern coast. That’s good news for our water supply, most of which comes from snowmelt in the Sierra Nevada.

Just three months ago, almost the entire state was experiencing severe to exceptional drought. While recent storms have helped ease drought conditions, about half of the state still remains in “moderate to severe” drought, according to the U.S. Drought Monitor.

Snowpack is far above the amount we usually have this time of year, and ideally that snow will slowly melt over the spring months and help refill the reservoirs that hold most of our water supply.

Some of those reservoirs have risen to above-average levels for this time of year — for example, Lake Oroville, the state’s second-largest reservoir, is 116% of the average for this time of year. But Lake Shasta, the state’s largest reservoir, remains at 84% of average for this time of year, according to the California Department of Water Resources.

While all this rainy and snowy weather has helped improve snowpack and surface water levels, it’s done far less for groundwater, which much of the agriculture industry relies on, particularly during dry years.

And the Colorado River, the Southland’s other main water supply, has also not benefited as much.

Furthermore, the climate crisis is driving what many scientists call “weather whiplash.” That’s shrinking the spring and fall seasons, which is not only bad for water management — we don’t want all that snow melting at once and causing dangerous flooding — but also for wildlife and plant species that are struggling to adapt to these increasingly extreme changes.

What is the U.S. Drought Monitor?

At this point, you’ve probably seen a lot of versions of those maps with splotches of red, orange and yellow, like the ones in this story.

Those are created by the U.S. Drought Monitor, which provides an updated map every week on drought conditions across the U.S. It started in 1999, when parts of the east, southeast and midwest were in the grips of record-breaking drought and heat.

The data to create those maps is compiled by the National Drought Mitigation Center at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA). The idea is to give a big-picture view of drought to help with planning efforts and trigger aid. For example, the USDA uses it to declare disasters and low-interest loans for aid. State, local and tribal governments use it to coordinate drought responses.

The map labels drought by levels of intensity, from “abnormally dry,” to “exceptional drought,” and aims to estimate how long- or short-term those conditions are expected to be. Learn more here.

Drought in an era of climate change?

First, what actually is the official definition of drought?

The U.S. Drought Monitor defines it as “a moisture deficit bad enough to have social, environmental or economic effects” and labels dry periods on a scale of intensity, from “abnormally dry” to “exceptional drought.”

The National Weather Service defines drought as “a deficiency in precipitation over an extended period.” Then it breaks it down into four categories:

- Meteorological drought: the degree of dryness or rainfall deficit and the length of the dry period.

- Hydrological drought: the impact of lack of precipitation on the water supply.

- Agricultural drought: the impacts of drought on agriculture based on factors including lack of rain, how dry the soils are, and groundwater and reservoir levels needed for irrigation.

- Socioeconomic drought: occurs when the demand for needs such as food exceed the supply due to a weather-related deficit in water supply.

So, if we’re just talking semantics, you could technically say we’re out of drought, but when you dig into definitions within that definition, the picture becomes a lot more complicated.

And our understandings of what’s normal drought and what isn’t are changing as global carbon pollution pushes us into a drier climate as a whole — what’s called “aridification.”

A changing water cycle

Maybe you remember the concept of the water cycle from elementary school: when water from lakes, rivers and the ocean evaporates, it condenses to form clouds, then falls back to the earth in the form of rain or snow.

But as our climate heats up, water on the landscape, such as mountain snow and rainfed streams and lakes, evaporates more quickly and dries out soils faster. That leaves less water for humans and the animals and plants that rely on that surface water, and also leads to a “thirstier” atmosphere, which then dumps that evaporated water in the form of increasingly intense storms, or atmospheric rivers.

That’s why the climate crisis is making California’s drought-to-deluge cycle even more extreme and less predictable.

“As the climate continues to warm, we're going to need to continue to better account for this so that we can manage our water resources in a way that better reflects this new reality,” said Joaquin Esquivel, Chair of the State Water Resources Board, in a segment on the LAist 89.3 daily program AirTalk in July.

A changing water cycle is part of aridification and the shifting definition of drought. It’s a big reason California is expected to lose at least 10% of its total water supply as soon as 2040 — that’s more water than the state’s largest reservoir, Lake Shasta, can hold at capacity.

“Droughts and floods are a common part of California's climate, but without a doubt, climate change has worsened the severity of those problems,” Peter Gleick, co-founder of the Pacific Institute, an Oakland based nonprofit that focuses on the global water crisis, said on AirTalk. “We have to understand that we're not facing a temporary short-term problem, but a permanent shift in our climate.”

That means drought or no drought, we need to continue to use less water in cities — one reason why water restrictions have yet to end — and agriculture, Gleick said. He said there are still significant water savings possible both inside and outside of homes and businesses, but the major conversation will have to be about agriculture, which uses 80% of the water in California. Fallowing land, shifting to less water-intensive crops, and improving water use efficiency are needed strategies to adapt, and are particularly important for restoring groundwater supplies, Gleick said.