This story is free to read because readers choose to support LAist. If you find value in independent local reporting, make a donation to power our newsroom today.

A Tale Of Two Friends, Thousands Of Refugees And A Long, Long Wait

Sometimes it's hard to see how decisions made in Washington affect us in Southern California, but for one man in Anaheim, a Trump administration decree on refugees has hit close to home.

Federal officials last month sharply lowered the ceiling in the current fiscal year for refugees allowed into the country. The 30,000 who could be let in represents the lowest number on record.

For Kewa Sharif, the number has real meaning. He's been awaiting word on whether his close friend in Iraq can follow him to California as a refugee.

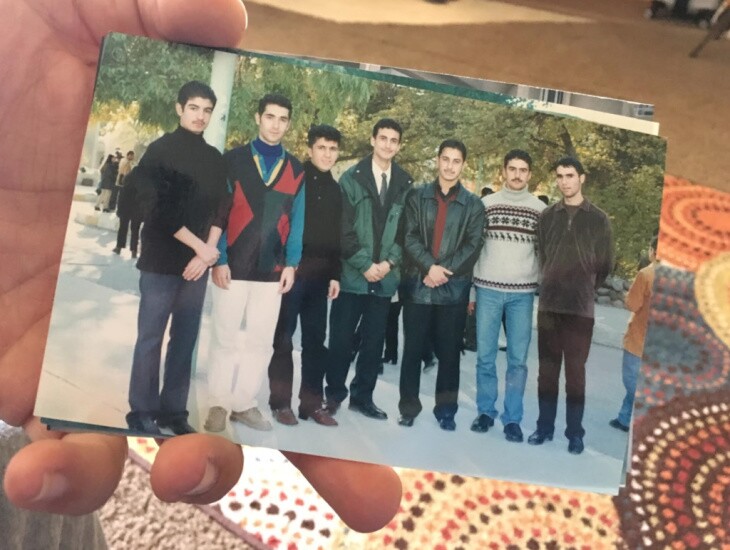

In his apartment recently, the 38-year-old Sharif flipped through a stack of old photos from his life in Iraq -- photos from college, from social events, and some in which he and others are flanked by men in green Army fatigues.

"The Americans," Sharif explained.

During the U.S. invasion of Iraq in 2003, Sharif helped American troops working in an information technology job. So did another young man in many of the photos.

"That's Rebaz," Sharif said, pointing to a picture of his lifelong friend from their hometown in the Kurdistan region of northern Iraq.

"When I was a child, I knew Rebaz," he said. Sharif, two years older, was in the same class as Rebaz's brother, and they all grew up together.

"The same school, primary school... then the high school, then the college, every year together," Sharif said, speaking in the English he's been perfecting since he arrived here three years ago.

When the U.S. invaded their homeland, Sharif and Rebaz gladly took sides. They opposed the country's leader, Saddam Hussein, and they wanted democracy.

"When America came to Iraq, many people, most people actually, [were] happy with the news, because the regime [was] a dictator," Sharif said.

But as the war wound down, life in Iraq remained unstable, Sharif said. In 2008, he applied to come here through the U.S. Refugee Admissions Program. Rebaz followed suit the following year.

In May 2015, with a wife and a young daughter, Sharif arrived in Anaheim, where they settled down.

Rebaz's refugee application, meanwhile, seemed to be moving forward.

He had listed Sharif as his U.S. tie, the person who would help him settle in when he arrived. In early January 2017, a representative from the World Relief resettlement agency came to Sharif's door with good news: Rebaz would soon be on his way.

Sharif signed paperwork, assuring the representative that he would be responsible for his friend.

"I said, 'Yes, of course,'" Sharif said, "because Rebaz [is] my friend."

Jose Serrano, senior immigration specialist with the Garden Grove office of World Relief, said it should have taken just about 30 days for Rebaz, his wife and two children to travel to the U.S.

HITTING A WALL

But less than three weeks after Sharif received the news about his friend's impending arrival, a newly inaugurated President Trump signed an executive order banning all immigrants, refugees and travelers from seven Muslim-majority countries. The list included Iraq.

Chaos erupted at LAX and other airports as people arriving were detained, and some were turned back.

The resettlement of Rebaz and his family ground to a halt.

Since then, "nothing, nothing at all," said Rebaz, speaking from Iraq.

He asked that his last name not be used, saying he feels unsafe in his home country. There are active terrorist groups in the area, he said, and he feels especially fearful because he worked for the U.S. military during the war.

Rebaz has tried to learn where his refugee case stands, but there is only so much the resettlement agency can give him.

"I sent an email, I did a phone call with them," he said. "My case, it's pending. I don't know."

Serrano with World Relief said the timing of Rebaz's case doomed a quick resolution.

"If he was assigned to us a little earlier, or perhaps allocated at an earlier time, he might have had a chance," Serrano said. "This is the story of thousands and thousands of refugees."

Iraq was eventually taken off the travel ban list, after Trump's initial order was challenged in court and changes were made. The U.S. Supreme Court eventually upheld a modified version of the president's order.

Since then, Rebaz hit just about every new roadblock. For a time, only refugees with close U.S. relatives were allowed in -- he doesn't have any. Extreme vetting has led to more delays, slowing refugee arrivals to a crawl, particularly those from Muslim countries.

REFUGEES DECLINE IN PRIORITY

Then the annual cap for refugees was slashed: President Obama had set a ceiling of 110,00 refugees for the 2017 fiscal year. The Trump administration cut the allowance in half, and again lowered the cap to 45,000 for fiscal year 2018.

Even that lower number has not been met. New State Department numbers show only 22,491 refugees were admitted in the last fiscal year, which ended Sept. 30.

Speaking with reporters recently, Secretary of State Mike Pompeo gave the administration's rationale for why the refugee numbers were cut. He cited a focus on national security and a kind of trade-off with asylum cases as the U.S. receives more migrants from regions like Central America.

"This year's refugee ceiling reflects the substantial increase in the number of individuals seeking asylum in our country, including a massive backlog of outstanding asylum cases, and greater public expense," Pompeo said.

The U.S. has historically opened its doors to refugees fleeing war and other crises that threaten their lives. This year's refugee admissions, like the ceiling numbers, represent a significant decline.

In recent pre-Trump years, refugee arrivals to the U.S. have ranged from a high of 84,994 in fiscal year 2016 to 56,424 in fiscal year 2011.

The partial lifting of the refugee bridge is just one of the steps taken by President Trump as he reels in legal immigration and steps up enforcement against unauthorized immigrants.

So has the era of the U.S. being a welcoming place for refugees come to an end? Yen Le Espiritu, a professor of ethnic studies and critical refugee studies at University of California, San Diego, said there's a bit of a myth to the "welcoming" narrative. What welcome mat there once was has now been pulled away for most, she said.

"Maybe on a case-by-case basis, someone will get lucky. But on the level of policy, it is a very difficult time for refugees," Espiritu said.

WAITING AND WAITING

On a recent Saturday, Kewa Sharif, his wife and their 8-year-old daughter prepared to head to a local festival celebrating their Kurdish culture.

But even as they settle in and make a life in the U.S., Sharif said he worries about his friend's well-being back home.

"Waiting, waiting is more painful for him, for all refugees," he said. "Actually, it is not just painful, because it is the risk, a risk for themselves, because many terrorist groups are over there."

When they talk on the phone, Rebaz said, his friend tells him to keep his chin up and not lose hope.

"He tells me, 'You will go to U.S.A. I am here, and I will help you,'" Rebaz said.

He hopes this will come true.

"If I have luck," Rebaz said, "maybe next year, I will be one of the 30,000 people to go to U.S.A."