This story is free to read because readers choose to support LAist. If you find value in independent local reporting, make a donation to power our newsroom today.

LA Latinos Took A Big Financial Hit During The Pandemic. Here’s How Some Are Trying To Bounce Back

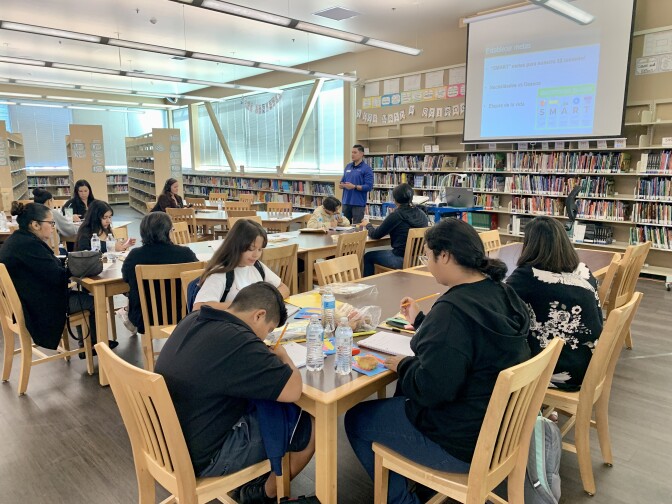

In an elementary school library in Bell one recent morning, about a dozen parents and a few children clustered around long tables as a financial instructor flipped through PowerPoint charts, talking about budgeting.

“Here’s how to build your ideal budget …” began the instructor, Everardo Velasquez, in Spanish. “An ideal budget means that our dwelling cost will not be more than 35% of our income … transportation and car payments, not more than 20% … food, 20% …”

It was a financial literacy class put on for parents whose children attend the Magnolia Science Academy, one of a group of public charter schools located around Southern California, many located in largely Latino communities.

Staff here and on other Magnolia campuses brought in the workshops earlier this year, after noticing that as school and life returned to semi-normalcy following the worst of the pandemic, parents and students were mentioning money problems more than usual.

As he spoke in Bell recently, Velasquez, with the SchoolsFirst Federal Credit Union, would get the occasional comment from a parent. At one point, a woman in the back raised her hand. She said her family was struggling “just to eat, let alone pay rent.”

As Velasquez sympathized, the woman went on: “Each day, it’s more difficult.”

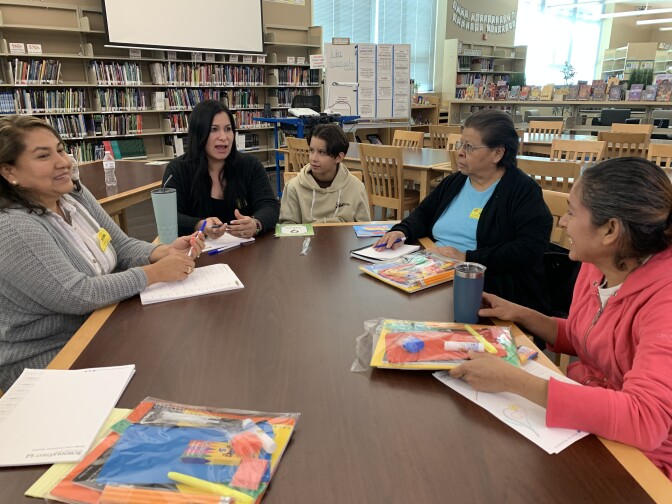

After the class ended, a few of the moms stayed behind to chat. Teresa Mendoza, whose husband works as a gardener, talked about how as he lost work during the shutdown, the family began cutting corners.

“In place of meat, we bought seeds — rice, beans, lentils,” Mendoza said. “We ate more naturally.”

With their forced vegetarian diet, Mendoza joked, “We came out of the pandemic healthier!”

But not financially, she said. Her husband let customers who couldn’t afford his services slide on payments; she said people still owe him. And though he’s working full-time again, now they have inflation to contend with.

“For his work (truck), it used to cost him about $50 to fill his tank,” Mendoza said. “Now, it is costing double. So this is affecting us more than the epidemic — that is the truth.”

Another mom, Imelda Lopez, chimed in.

“This,” Lopez said wryly, ”is the epidemic, really.”

Feeling the post-pandemic pinch

The pinch of the current inflation crisis is universal, as food and gas prices grow prohibitive and rents soar. But it’s being felt deeply in Latino communities that were hit hard by the pandemic.

Latinos in California suffered not only the highest rates of COVID-19 infections and deaths, but a big financial hit as well.

According to the state Legislative Analyst’s Office, Latinos in California endured a disproportionate share of job losses during the pandemic: In 2020, Latino workers made up 38% of people employed in the state, but accounted for 50% of jobs lost. Service-related industries, in which Latino workers are heavily represented, especially struggled during the shutdown.

As life has returned to semi-normal in the post-pandemic economy, there’s been a ripple effect for these workers and their families, say experts who study California Latinos’ financial well-being.

“As we've come out of the pandemic, one marker that's always clear is that it's going to be more difficult for Latinos to bounce back,” said USC sociologist Mindy Romero.

In 2019, Romero reported on how in spite of a declining poverty rate and a growing Latino middle class in California, there remained challenges to upward mobility: uneven access to banking and credit, a persistent education gap, and a lack of generational wealth. Opportunities were especially limited for people lacking legal status.

Romero says all of these factors left Latinos in California especially vulnerable to a challenging economy — like the one consumers are experiencing now, as inflation soars.

‘Pushed back gains’

Complicating the financial hit of the pandemic for Latinos were the costs faced by those left healthy and working who had to help less-fortunate family members.

“People who were working all of a sudden were trying to provide for more than just who they might have been before the pandemic,” said Bill Maurer, director of UC Irvine’s Institute for Money, Technology and Financial Inclusion.

He said this caused even some not directly affected by illness or job loss to get behind financially. Maurer and other UCI researchers have been looking into the financial status of Latinos post-pandemic as part of a forthcoming study. Getting “back to normal” has proven elusive for people they’ve surveyed, he said.

“Getting back to work, the ‘getting back to normal,’ plus inflation … hit some of these families harder than others, because inflation was highest around things like food and gas, transportation, housing — and gobbling up much more of their wages than it had before,” Maurer said. “So it just compounded everything, and we've seen that kind of pattern continue.”

UCI has partnered in its research with Abrazar, a Westminster-based nonprofit that among other things provides culturally relevant financial education for Latinos in Orange County through a United Way program called SparkPoint OC. Abrazar CEO Mario Ortega said in the past, they’d focus more on short-term and long-term financial goals with people they served. He said he’s noticed a shift toward simple survival since the pandemic.

“It just really pushed back any gains that the community had made,” Ortega said. “It's so difficult for a family to try to focus on financial goals, short term or long term, when they're just trying to not get evicted, or trying to feed their family, or trying to be able to access health services.

“So the progress that we've made of trying to be able to move the family to look at short-term and long-term financial goals in a new way, it's become a lot harder when they're just trying to survive,” Ortega said.

Budget, budget, budget

Once behind, it is difficult to catch up, said USC’s Romero.

“When you get behind and you're already on the edge, it's really hard,” she said. “It almost feels like you have to win the lottery to catch up. And that's our economic system … the safety nets are incredibly minimal.”

Romero, Maurer and others believe broader financial reform is necessary to address wealth inequities for communities of color.

But there are at least small steps families can take to address debt, said Everardo Velasquez, the financial instructor with SchoolsFirst Federal Credit Union.

“I know that we sort of have, in our mind, an idea of, how much money we're bringing in as a family and what expenses we have,” Valesquez told LAist afterward. “But when we want to start taking control of our finances to reach our financial goals, to pay down our debt, we want to have a better picture of what our cash flow looks like from month to month.”

Taking detailed stock of income, debt and expenses, and making a budget in writing, is a good start, Velasquez said. So is talking expenses through with family members in the household.

“Maybe conversations around money can be seen as a little taboo or, you know, we don't talk about it so much,” Velasquez said. “So kind of normalizing that, right?... It’s OK to talk about it. Let's get on the same page. Let's create a budget together.”

This should include examining bills together to distinguish wants from needs, he said, and lowering costs as needed to prioritize debts.

'How do I belt-tighten this?'

All that said, it’s hard to lower even necessary costs right now, said Bell mother Imelda Lopez.

“Sure, we can try to cut, we can eat something different,” Lopez said, “but transportation to work, rent — these are costs that you can’t let go of.”

Which prompts a frustrating question, she said: “How do I belt-tighten this?”

Magnolia school administrators obtained grant funding to help with a few related services for school families, including mental health and financial workshops.

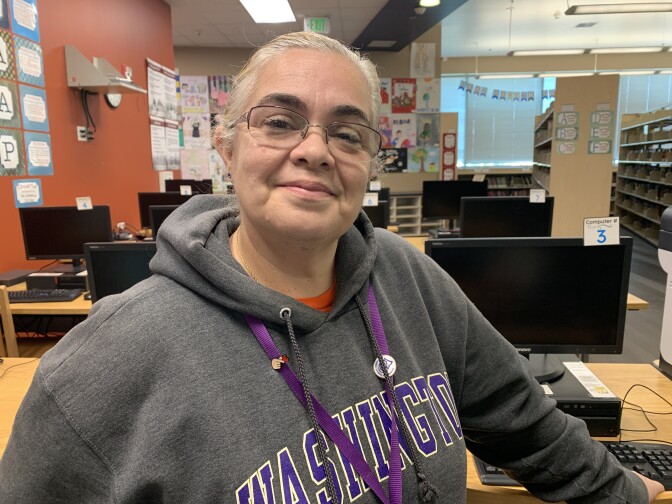

Bell campus Spanish teacher Marlene Castañeda said the need for the financial classes became obvious as she and other teachers heard stories like these:

“Families that lost a grandparent, that they were counting on that Social Security check and now it's gone,” she said. “People that became very ill and now they cannot work and they're on disability. That is if they are legally documented, because if they are not, they are really on zero.”

As the school reached out, including with home visits, staffers learned of more families doubling up in a home or apartment to save money, she said, kids whose parents could not afford school supplies, and parents talking about limiting their grocery shopping.

“I don't remember seeing this before, before the pandemic,” Castañeda said. “Not to this extreme. So families are definitely struggling.”

Magnolia administrators say they plan to bring the financial literacy workshops back to Bell and other campuses next semester.

Some tips to help become more financially stable

Take advantage of community programs: Such as food baskets, holiday toy giveaways, career training and skill building

Sign up for financial benefits and assistance programs: See if you’re eligible for food assistance through CalFresh. The federal Affordable Connectivity Program, can help reduce monthly internet or cell phone bills. Some utilities also offer discount programs and payment plans.

Establish a budget: Tracking your income and expenses is the first step to creating a saving and spending plan. Download a budget tracking sheet.

Have a support system: Ask a family member or friend to help keep you accountable to saving and spending goals. Create a "saving group" with friends to encourage saving habits.

Avoid taking out payday loans: These have very high interest rates. Check with your bank or credit union to see if you qualify for a personal loan with a lower interest rate. If you can, try to save up an emergency fund for unexpected expenses.

Take advantage of sales, coupons, discounts: Just be careful not to over-purchase! Grocery store reward programs can be helpful. Also take advantage of discounts for seniors, veterans, etc.

Set boundaries: For example, set limits on spending expectations with children and family members.

Don’t be afraid to ask for help: If you have a bill you can’t pay, reach out to the billing department or lender to ask about options.

Courtesy of Abrazar and SparkPoint OC