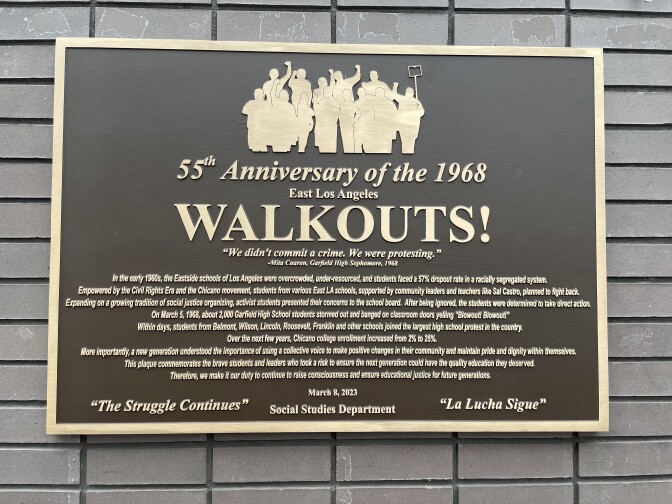

At Garfield High School, a plaque was unveiled Wednesday to commemorate the 55th anniversary of the East L.A. Walkouts.

The East L.A. Walkouts, or blowouts as students called them, marked the start of the urban Chicano rights movement as thousands of Latino students from five East L.A high schools — Wilson, Garfield, Roosevelt, Belmont and Lincoln — poured out of classrooms to protest unequal education.

The backstory

On March 1, 1968, Wilson High students were the first to stage a walkout, but this one was unplanned.

"We were not a bunch of politically-sophisticated folks. We knew something was wrong. We knew we were mistreated," said Luis Torres, former editor of the Lincoln High School newspaper who documented the walkouts.

Four days later, a fire alarm went off at Garfield High and students there flooded out of their classrooms. They were frustrated with feeling discriminated against and being subjected to a sub-par education. At the time, Latino students were tracked into vocational classes that steered them away from higher education.

Looking back at the walkouts today

At the plaque's unveiling ceremony on Wednesday, three former student leaders reflected on their actions and what they mean for today's youth.

Vickie Castro, who was a student at Roosevelt High School, noted that, from kindergarten through twelfth grade, she "never had a Chicano principal, teacher or counselor. ” She also made it a point to recognize the other students who joined the protest.

“Yes, we had a leadership role," she said, "but there were thousands of students who walked out that day. They all supported the changing of our schools. Those are the students this plaque represents.”

Cassandra Zacarías Alarcón was a 15-year-old sophomore when she helped lead the walkouts at Garfield High School in 1968. “We were excited, but we were also very frightened," she said. "We didn't know if the police were going to descend on us. We didn’t know if the other students would join us, or if it would just be us four with our picket signs, marching alone in front of the school.”

“Look at all the things going on in our country," she told the students in the audience. "Don't let anybody ever tell you that you can't read a certain book, or that you don't have a right to your body . . . We're counting on you, because now we're the senior citizens, and you are the faces of what's coming. So get out there and make a difference.”

1968 student leaders Vickie Castro, Rachael Ochoa and Cassandra Zacarías Alarcón and current Garfield high school students unveil the plaque as their U.S. history teacher, Juan García, cheers them on.

Garfield High now

Today, Garfield High School is led by principal Andrés Favela, whose mother is a Garfield High School alumna. The school currently serves about 2,400 students and, unlike in the sixties, they're encouraged to pursue higher education.

"We take much pride in the history of our school. And we just want to make sure that as students spend their time here, they never forget those that came before them," he said.

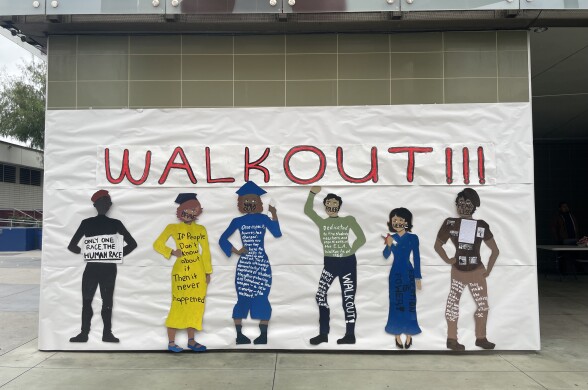

Juan García has been teaching U.S. history at Garfield High School for the past 13 years and routinely invites the former student leaders to speak with his students. He hopes the plaque will encourage future generations to learn about what took place on their campus, long after he's gone.

“We are not in the curriculum, we are not in the history books. So we need to include ourselves in it. We need to bring that material to life," he said.

García's students include Aimee Perales, a 17-year-old senior who graduates next week and who will major in mechanical engineering at Yale come fall. She credits García with providing her and her classmates with a strong sense of self. She also sees her educational journey as part of a legacy.

“Because [students in 1968] stood up and fought for what was right for us Chicanos, I am where I am today," she said.