This story is free to read because readers choose to support LAist. If you find value in independent local reporting, make a donation to power our newsroom today.

A mob killed a tenth of LA’s Chinese population. 150 years later, there's a push to remember

Michael Woo was born and raised in Los Angeles and went on to serve as the city’s first Asian American councilmember. A fourth-generation Chinese American, he also took on the role of advocate for other Angelenos of Asian descent.

Yet it wasn’t until several years ago — when he was in his 60s and retired from politics — when Woo learned that one of the country’s worst attacks on Chinese people had taken place in Los Angeles.

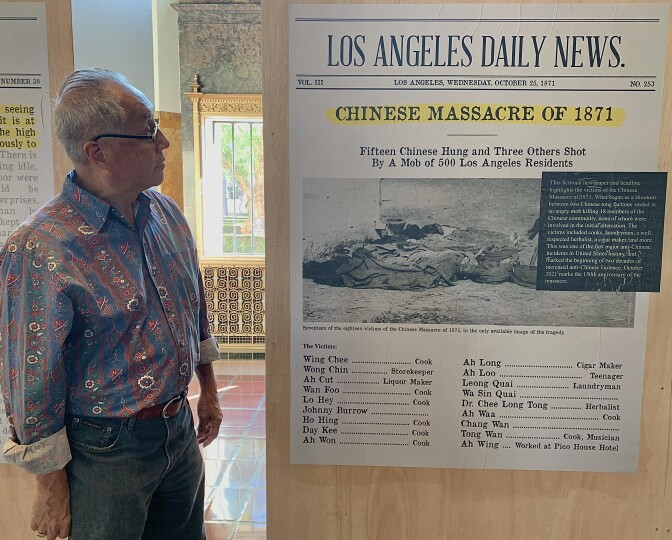

On Oct. 24, 1871, a mob of hundreds descended on a Chinese neighborhood just blocks from where Union Station stands today, killing at least 18 people — about a tenth of the city’s Chinese population.

“My first reaction was shock," Woo said, "because I had no idea that anything like this had ever happened."

Jason Chu, an activist and rapper, said he too was surprised when he heard a few years ago about the massacre — though not about the erasure of Asian Americans from history.

“I think that 99% of L.A. — Asian American or otherwise — has no clue that this happened,” Chu said. “It's just not taught in the textbooks.”

But Woo and Chu see a chance to educate the public about the deadliest attack on Chinese people in California history. Both are among the dozens who’ve joined a new campaign to build a memorial to the 1871 victims.

“Most people can't name a single, historical Asian American,” Chu said. “I don't blame people for this. But we have an opportunity right now.”

The memorial plan is gathering momentum because of the massacre’s 150th anniversary and its grim resonance amid a surge in anti-Asian incidents during the pandemic.

In April, weeks after six women of Asian descent were gunned down in Atlanta, Mayor Eric Garcetti expressed urgency to mark the massacre with a memorial.

“One of the more bitter effects of this pandemic is the rise of hate crimes against Angelenos and Americans of Asian or Pacific Islander origin,” Garcetti said. “We have been here before, and we must not forget that.”

Creating a memorial to the 1871 victims was one of the top recommendations of the mayor’s Civic Memory Working Group, a panel charged with assessing the city’s treatment of history.

The city is providing $250,000 dollars for the project, which Woo, one of the group’s co-chairs, said would fund a design competition “to create a world-class memorial that people will want to come to see.”

Christopher Hawthorne, the city's Chief Design Officer, said the memorial could end up being a combination of a permanent space and “temporary, ephemeral, even mobile events” in different parts of downtown.

The massacre played out across almost the entirety of what was then Los Angeles, Hawthorne points out. One of the gallows was set up at Goller's wagon shop, where the parking garage of the L.A. Mall shopping plaza now stands. Another key site was under a mile away, near the corner of Broadway and Seventh, where justice of the peace William H. Gray is believed to have offered a cellar at his vineyard as sanctuary to some Chinese men who were fleeing the violence.

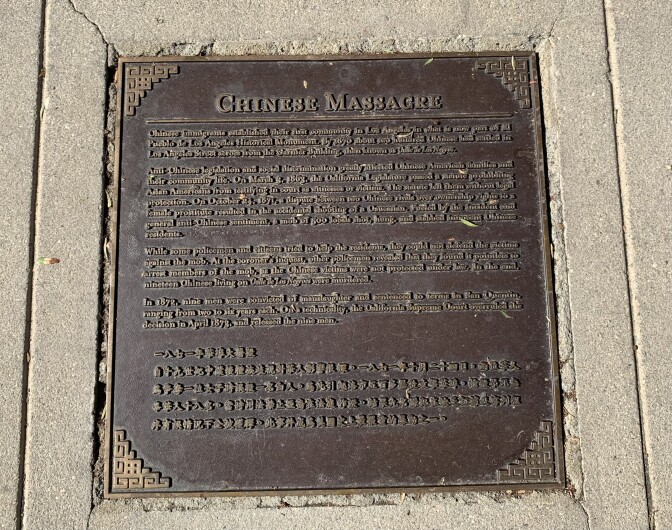

Currently, the only marker of the massacre is a sidewalk plaque on Los Angeles Street, near the Chinese American Museum and El Pueblo De Los Angeles plaza.

This area is where the attacks began. While details are debated, the basic chronology is this: two Chinese men from rival factions got into a gunfight over a woman.

A couple of non-Asian men who got involved in the shooting — a police officer and rancher — were struck in the crossfire. When the rancher died, news spread that the Chinese had killed a white man and a mob of 500 white and Hispanic men — about a 10th of the city's population — began to form in what was called Calle de los Negros, a seedy block with cheap housing that drew Chinese laborers.

Some of the Chinese men sought refuge in the sprawling one-story adobe Coronel Building. But then rioters began to shoot inside.

“Some even got up on the roof with hatchets and tried to get in by cutting holes into the roof of the building, and then firing shots into the building hoping to hit somebody who was Chinese,” Woo said.

Within several hours, the attackers had hanged or shot to death at least 18 Chinese males.

Among the dead was the city’s most prominent Chinese Angeleno — a doctor named Chee Long "Gene" Tong, who treated patients both in and out of the Chinese community.

One of the youngest victims was a boy of about 15, Ah Loo, who had just arrived from China a week earlier. According to The Chinatown War: Chinese Los Angeles and the Massacre of 1871, Loo was walking home with two other Chinese men when they were captured by rioters and strung up at one of several makeshift gallows set up just hundreds of yards away from where City Hall stands today.

Eight of the attackers would be convicted but the judgments would be overturned on a technicality, setting the men free.

One of the gallows was set up outside a wagon maker’s shop – what is today the garage for the LA Mall, sandwiched btw City Hall & the Federal Building.

— Josie Huang (@josie_huang) October 21, 2021

The shop apparently had an awning that was used for lynchings. pic.twitter.com/bYH48faaWE

The attacks in L.A portended other anti-Chinese incidents across the West, including the forced removal of Chinese residents from cities such as Eureka and Antioch, and another massacre 14 years later in Wyoming in which 28 Chinese miners were killed.

But up until recent years, the 1871 massacre was not commemorated in L.A., even by the Chinese American Museum.

That changed when David Louie, who serves on the commission of El Pueblo De Los Angeles, on a couple occasions more than a decade ago took his young sons to the small park across from Union Station (the to-be-renamed Serra Park) so they could observe a few minutes of silence for the victims of the massacre.

“I was having an opportunity to think about the people and the work they didn't do, the songs they didn't write, the poems they didn't repeat,” Louie said.

Leaders at the Chinese American Museum got wind of Louie’s gesture to the victims. Board president Gay Yuen said: “We were just amazed at the initiative that he took to commemorate those who died needlessly.”

Yuen said that was an impetus for the museum to start holding commemorative events a decade ago and to help plan more than a week of panels and performances this year, culminating in a special anniversary event on Sunday. Running concurrently is the 'Broken News' exhibit — featuring fictionalized newspaper front pages about the massacre — at Union Station, a very deliberate location choice given that's the area where many Chinese moved after city leaders had Calle de los Negros razed after the attacks. Chinese residents were forced out again by the construction of the train station in the 1930's.

For this reason, Union Station could be one of the places incorporated into a memorial. The working group, of which Louie and Yuen are also co-chairs, are staying open-minded about where the memorial would be placed, and what it would look like.

Community engagement, Hawthorne said, will be key to achieving the right scale and framing of the memorial, and working with those living nearby, so they’re not negatively affected by area revitalization.

“This is a really important tension to be aware of — the ways in which investment in new open space, even new transit lines or design features can themselves attract the kind of outside investment that can intensify displacement and gentrification pressures,” Hawthorne said.

It is mostly veteran leaders in the Asian American community who are leading the charge to drum up support for the memorial, but they have recruited younger people such as Chu, who was eager to help.

“So many of us grew up in this whitewashed school system, this whitewashed media system that told us, Oh, Asians may face discrimination, but that's just not seeing our faces on TV enough,” Chu said. “The reality is, you can go back 150 years and you see Asians getting stabbed, and shot and beaten in the streets.”

Chu first heard about the massacre from a song called "Yellow" by another young Chinese American artist, Lowhi. Chu was inspired to co-write the song, "Making the Banned" with Alan Z, a Chinese American singer based in Atlanta.

“They drove us out in the streets and called us demons in their steeples.

Killed us in the camps and in the Chinatowns.

This violence isn't random, It's just another round.”

For Chu, it’s never too late for people to learn their history.