This story is free to read because readers choose to support LAist. If you find value in independent local reporting, make a donation to power our newsroom today.

This archival content was originally written for and published on KPCC.org. Keep in mind that links and images may no longer work — and references may be outdated.

Robots steal port jobs — but they also fight climate change

A foulmouthed longshoreman named Frank Gaskin pointed his phone at a chain link fence at the Port of Long Beach last summer and made a video of the robots that had taken his and his buddies’ jobs.

In the video, flatbed carts glide by carrying cargo containers around the dock. They’re self-driving, guided by computers and magnets beneath the pavement. As one passes soundlessly near the fence, Gaskin yells, “f--- you automation mother f-----!”

At 21 of the 22 docks at the Port of Long Beach, most of the work of loading and unloading cargo from containers ships is still done by people, not by robots. The Long Beach Container Terminal, which opened in April 2016, is an exception. It requires two-thirds fewer workers than traditional terminals. And that frightens the International Longshore and Warehouse Union, which controls all the jobs at the docks.

Note: This video contains profanity that may offend some viewers.

But viewed from another perspective, automation is part of the solution to one of Southern California’s most vexing environmental problems: the worst air pollution in the country.

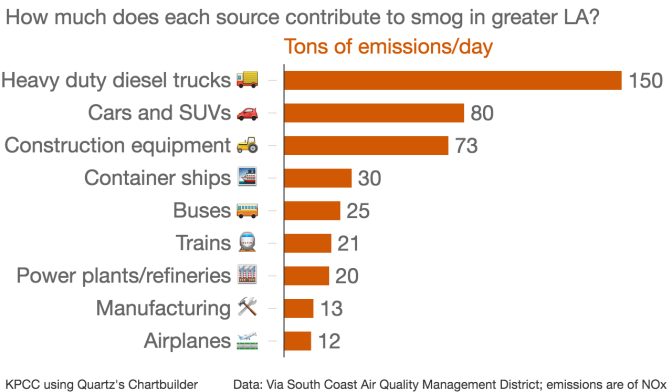

Diesel trucks and equipment are the largest contributors to that air pollution, and the ports are the largest single source of those emissions.

But the automated carts at the Long Beach Container Terminal run on electricity, which can be generated by natural gas or renewable energy. Look closely as the cart nears Gaskin’s camera, and you can see the words, written in bright white letters on a green background, “zero emissions.”

Gaskin captioned his video: “Automation in Long Beach Container Terminal will hurt everyone.”

But what if automating is also a way to help everyone by cleaning the air and fighting climate change?

Where people run the port

To understand how radically different the Long Beach Container Terminal is, you first have to visit a traditional terminal, where people control each piece of equipment.

Gary Herrera, the vice president of the ILWU Local 13, took me on a tour of the Everport Terminal at the Port of Los Angeles. He pointed out workers unloading containers, driving forklifts and operating cranes.

“Everyone you see, those are longshoremen,” Herrera said proudly.

There are just over 14,000 unionized longshoremen on the West Coast, but that number is half of what it was in 1960. That's even though the ports move more than 14 times as much cargo.

The ILWU’s founder, Harry Bridges, started preparing for automation in the 1950s. At that time, "automation" came in the form of containers that replaced individual bales, bundles and boxes of goods to be shipped. The containers carried more cargo and required fewer hands. Bridges signed an agreement with the terminal operators allowing that, but he did so only after ensuring his members got higher pay and pension guarantees.

And any new equipment they used would have to be operated by union workers.

"Even if it comes down to one person pushing one button to run a whole port,” Bridges reportedly said, “that person will be union.”

That agreement largely remains in place, and ILWU members are among the best compensated blue-collar workers in the U.S. They receive an average salary of $155,000 a year, pay almost nothing for their health insurance, and get up to six weeks of paid vacation.

The longshoremen owe their leverage to the fact that, unlike factories and auto plants, ports cannot be outsourced.

Where machines run the port

Ports can, however, be run by machines, computers, and, increasingly, robots.

My tour with Herrera continued as we headed across a towering bridge toward the Port of Long Beach and the Long Beach Container Terminal. Herrera’s mood changed as he looked across the water and saw remotely operated cranes and self-driving trucks.

"It makes me sick to my stomach," he said, tightening his hands on the steering wheel. "I look at this place, and I do not like what it stands for. These machines get rid of men."

I'd tried for weeks, unsuccessfully, to get into the Long Beach Container Terminal on my own. I even got so far as to get their president, Anthony Otto, on the phone. He agreed to show me around, but said I couldn’t record any audio, take any pictures, or quote him.

Then, the morning of the tour, he canceled. “It’s a sensitive time for us,” he said, referring me to his PR firm for further explanation.

The firm didn’t return my call.

Officials with the ILWU can enter the terminal at any time and bring guests. Herrera had invited me to come along.

He drove us into the terminal, and we stopped in front of LBCT’s 48 stacking cranes. They load containers onto semi-trucks that haul them out of the port to distribution warehouses. In a traditional terminal, workers operate them from booths on top, but in the LBCT, four people can control all 48 cranes at once.

“The same guy who used to drive the crane out in the yard eight hours a day is now doing it from a remote console, sipping coffee and listening to light music in air conditioning,” Otto said in a YouTube video touting the benefits of automation.

The ILWU estimates that two-thirds of the longshore jobs at LBCT have disappeared due to automation. Neither Otto nor anyone else from LBCT would confirm the number of jobs lost, nor comment on the record for this story.

But they say automation creates opportunities for new kinds of jobs, like mechanics to maintain the self-driving vehicles. And, they say, their robots are cleaner than the diesel fueled, human-controlled machines they’re replacing.

The Long Beach Container Terminal emits 85 percent less diesel soot, 58 percent less nitrogen oxide (a component of smog), and 33 percent less carbon dioxide than a traditional dock at the ports.

Those kinds of reductions give Adrian Martinez, an environmental lawyer with Earthjustice, a very different take on the automated equipment at LBCT than guys like Gary Herrera.

“It’s exciting to see zero emissions equipment actually on the terminal,” Martinez said. “Because from a basic level, we’re not going to solve the air pollution crisis in the Los Angeles area until we eliminate port and freight pollution.”

So, more robots?

In November 2017, the Port of Long Beach and the neighboring Port of Los Angeles pledged to dramatically slash their emissions by phasing out internal combustion engines. Their goal is to replace all diesel trucks and cargo-handling equipment with zero-emissions equivalents by 2035. Usually that means electric vehicles.

The big question is whether the ports’ new mandate will lead to more automation.

Currently, electric cargo-handling equipment is more than twice as expensive as its diesel equivalent. That could lead terminal operators to choose to automate to save on labor costs, said Thomas Jelenic, who represents terminal operators as the vice president of the Pacific Merchant Shipping Association.

“People generally won’t seek out automation in and of itself unless they can justify it in some way,” he said. “But if they’re forced to electrify, the costs of electrification then dictate the need to automate.”

But Mark Sisson, a port planner with the consulting firm AECOM, thinks concerns about price are overblown. He believes the price of electric cargo-handling equipment will drop now that there’s a mandate for the largest ports in the Western Hemisphere to buy it. And right now, at least three other marine terminals are testing human-controlled electric cargo equipment.

Rage against the machine

Of all the automated equipment inside the Long Beach Container Terminal, it’s the 72 self-driving vehicles that elicit the strongest reaction.

They’re the ones Frank Gaskin swore at in his video, and they’re the ones Gary Herrera glared as he stepped out of the SUV on the last stop on our tour.

“They got rid of jobs, there’s no more drivers,” he said, looking across the fence at the little green carts. “And so this is why we’re skeptical at all when they wanna say zero emissions.”

Because of all the uncertainty, the ILWU isn’t take any chances. In September 2017, Gov. Jerry Brown signed a budget bill allocating $900 million from the sale of carbon permits under California’s cap and trade program.

Up to $140 million will be sent to the ports for clean freight and ships, but the ILWU lobbied hard to ensure that none of it could be used for automated equipment. If the terminals want to automate, they have to do it on their own.