This story is free to read because readers choose to support LAist. If you find value in independent local reporting, make a donation to power our newsroom today.

This archival content was originally written for and published on KPCC.org. Keep in mind that links and images may no longer work — and references may be outdated.

Geysers in a ghost town: Why it's so hard for one desert city to save water

One might expect Beverly Hills or Palm Springs to top the list of cities that haven’t done a good job conserving water during the drought. Places with big green lawns and lots of landscaping. But no – that distinction goes to a small, sparsely-populated city in the high desert called California City.

In May – the last month cities and water agencies were required to meet mandatory state water conservation targets – California City missed its goal by 17 percent, more than anyone else.

To understand why California City has such a hard time saving water in the present, you have to understand its past.

In the mid-1950s, a professor-turned-real estate developer named Nat Mendelsohn began scouring the desert north of Los Angeles for cheap land with lots of water. He wanted to cash in on the real estate boom that was transforming LA County, which would grow by almost 50 percent between 1950 and 1960.

He wanted to create a new city, but one without the pollution, social strife and overcrowding he thought were ruining life in L.A. and other mega-cities. His city would be different. It would, according to an early brochure for California City, “be planned from the beginning, and will attempt to avoid the mistakes of the past, rather than repeat them.”

Mendelsohn found an ideal location 40 miles north of Palmdale in the Mojave Desert. Beneath a bountiful cotton and alfalfa farm, there was a huge aquifer. A 1959 article from the Los Angeles Evening Mirror News confirms, “Vast lake found underneath Mojave Desert.”

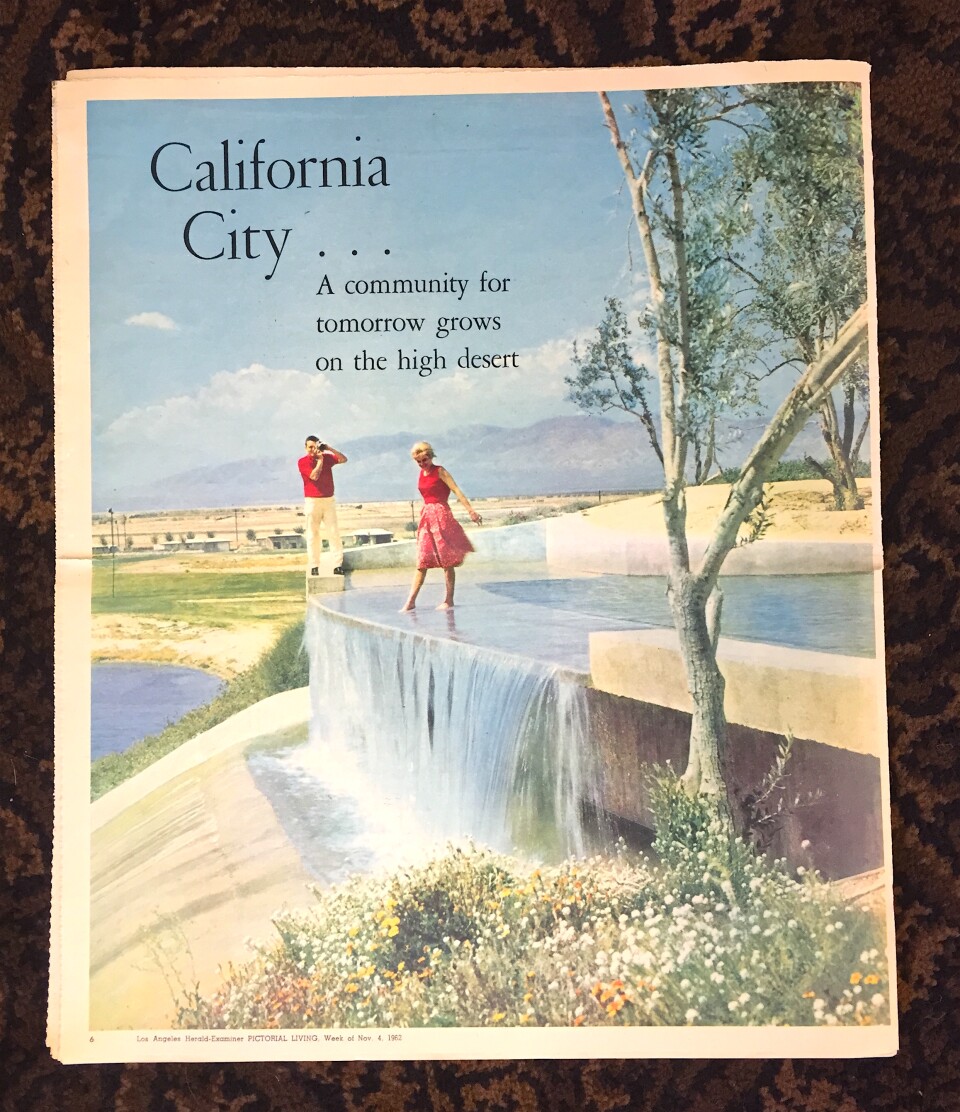

Using some sketchy real estate tactics, Mendelsohn bought the farm and immediately started planning for his city – one he envisioned would one day rival Los Angeles. He took out full page colored advertisements in LA newspapers, hoping to lure city-dwellers into the desert.

Steve Colerick has a box full of those ads. He's the president of the California City Historical Society and the town's former police chief.

He pulls out a copy of the Los Angeles Herald Examiner from 1962. A blond woman is dipping her toe in a man-made waterfall in front of distant desert mountains.

The headline is: California City, a community for tomorrow grows on the high desert.

But Mendelsohn didn’t wait for tomorrow to begin planning. He began immediately. He cut parkways and cul-de-sacs into the desert, even giving them suburban sounding names like Poppy Boulevard and Evelyn Avenue. He built his waterfall. And he put in water pipelines – 170 miles of them, curving through the desert along empty lots.

“They wanted an image that if you moved here, this was waiting for you,” Colerick said.

Except there was a problem. The people didn’t come.

The industries Mendelsohn was banking on to relocate, many of the aerospace-oriented, didn’t materialize. And it turns out not everyone was interested in remote desert living. Today, there are more vacant lots than homes. The city only rivals LA in one way: it’s size. California City is the third largest in the state by area, but less than 15,000 people live there.

“Today you couldn’t develop like this. They don’t allow you to develop like this. And we’re probably the model of why you don’t,” said Craig Platt, the director of Public Works in California City.

A particularly vexing problem is all the waterlines Mendelsohn put in. The city’s current meager tax base isn’t big enough to cover the ample maintenance costs, which were intended to be paid by the thousands of new residents who never arrived. So the pipes just sit there, rusting. And, recently, they began causing huge, dramatic blowouts

Mayor Jennifer Wood was driving home one day when she saw what she thought was a house on fire in the desert.

"It looked like a plume of smoke," Wood said.

But as she drove closer, she realized it wasn’t smoke at all– it was a geyser of water shooting 100 feet into the sky.

In 2015, the city had 400 mainline water breaks – sometimes up to six in a day. Water breaks blasted a hole into a house, ran like rivers down the street, and chewed away at roads, tossing huge chunks of asphalt into the air.

“I always worried about the loss of life,” Wood said. “You can see it tearing up a road, well that’s a very hard substance. What would it do to a child?”

City and state officials agree that these breaks are the reason why California City never met the state’s demand that it cut water use by over a third. The city is starting to replace its aging water pipelines, but it’s a slow, expensive process.

“The bottom line is money,” Wood said. “We could do a whole lot with half a billion dollars. But we’re not wealthy.”

But it seems like there are some cost-effective fixes the city hasn’t pursued. In December, the manager of the city-owned golf course, Bob Dacey, proposed ripping out 20 acres of grass. The removal would cost over $225,000, but he said it would pay for itself in less than three years and then save the city $80,000 a year in water expenses. (The city uses 85 percent recycled water on its largest golf course.)

The city council didn’t go for it, something Dacey attributed to politics and “a lack of ability to try something different.”

Mayor Wood, on the other hand, said the city simply didn’t have the money to front the upfront cost because it was spending so much on repairing its water infrastructure – which she said would ultimately result in more significant water savings.

Still, when I visited California City, I saw sprinklers running on the golf course greens during the middle of the day – something Steve Colerick, who lives alongside the golf course, says is common. He thinks the city can do better and is blaming its water conservation problems on a lack of money and poor planning.

“Any problem any of us had, it shouldn’t wait until someone else points it out to you,” he said. “You solve it yourself.”

City officials say they are solving it: major waterline breaks are way down compared to last year. Platt says his department is no longer spending all its time chasing leaks.

“The main goal is to manage the water system,” he said, “Not let the system manage the department.”

It appears to be working: in June the city used 19 percent less water than it did in the same month in 2013. But now that the state has rolled back mandatory water conservation, water use in California City is rising again (it’s up 26 percent since May). And this time, leaky pipes don't seem to be to blame.