If you value independent local news, become a sustainer today. Your gift could help unlock a $1M challenge.

Pioneering LA Politician Gloria Molina Has Died At The Age Of 74

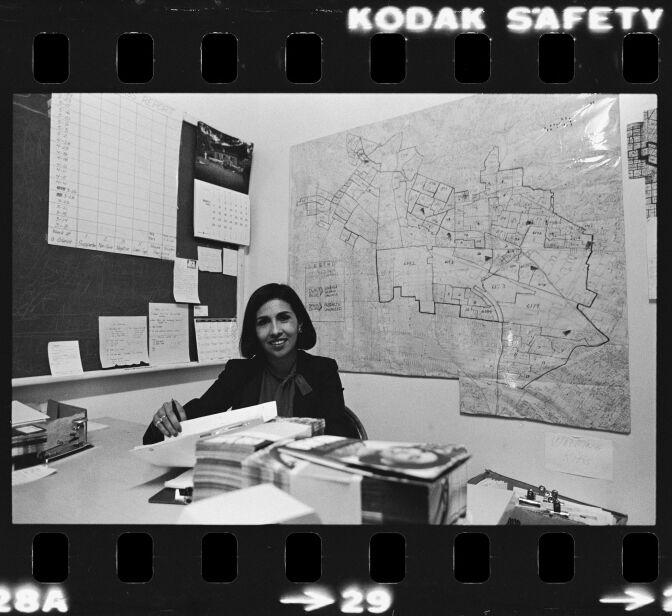

Gloria Molina, the political pioneer who was the first Latina elected to the State Assembly, the Los Angeles City Council, and the L.A. County Board of Supervisors, has died at age 74.

Molina had announced on March 14 that she had terminal cancer and was entering a “transition in life.” She died Sunday in her Mount Washington home, according to a statement released on her official Facebook page.

It is with heavy hearts that our family announces Gloria’s passing this evening. She passed away at her home in Mt. Washington, surrounded by our family.

Gloria had been battling terminal cancer for the past three years. She faced this fight with the same courage and resilience she lived her life. Over the last few weeks, Gloria was uplifted by the love and support of our family, community, friends, and colleagues. Gloria expressed deep gratitude for the life she lived and the opportunity to serve our community.

Gloria Flores, a close friend of Molina's, confirmed her death, saying she last saw her on Wednesday. "At least she is not suffering anymore," Flores said.

Longtime colleagues and friends say Molina will be remembered for a variety of accomplishments, particularly her many battles on behalf of L.A.’s Eastside.

In a 2017 Cal State Fullerton oral history, Molina talked about being the eldest of 10 children of a working-class Mexican mother and Mexican American father.

“I was brought up in a little barrio called Simons, in Montebello, where everyone spoke Spanish,” Molina said. “My father was a construction worker; my mom stayed at home, raised all of the kids. I was always reminded that I was the oldest and so I had to set the example for the family.”

Those close to Molina say these roots grounded her, particularly in her service to the communities she represented.

‘No hesitation’ to fight unauthorized sterilizations in court

Antonia Hernández met Molina in 1974, about eight years before Molina would be elected to the Assembly. Hernández, at the time a novice attorney, was seeking a Latina organization to join her in a class action lawsuit against L.A. County-USC Medical Center for carrying out unauthorized sterilizations on Latinas who were delivering their babies at the county hospital.

In the mid-1970s, Molina was president of a Latina women’s rights group, Comisión Femenil; Hernández asked the group to join the suit.

“If you become a class plaintiff as they did, and you lose a case, you might be liable for attorneys' fees and court fees,” said Hernández, now president and CEO of the California Community Foundation. “Gloria had no hesitation.”

While the court ruled against the plaintiffs, the case ultimately led to new state policies, including the repeal of state eugenics laws that had led to thousands of unauthorized sterilizations over the years, mostly performed on women of color.

As a Mexican American woman, Molina understood the lived experience of her community, colleagues and friends say, and this would shape her lifelong work.

“We women have children. We are the mothers. We are the ones that nurture a culture,” said Hernández. “Gloria was not only just a woman — [she was] a working-class Chicana coming from a very traditional family that, you know, would speak with a voice that was different.”

Molina championed causes that affected working-poor families and sought ways to improve their quality of life, Hernández said, “never forgetting where she came from.”

A career that started in college

Molina became involved in political activism while a student at East Los Angeles College, participating in student walkouts and the Chicano Moratorium in opposition to the Vietnam War.

After helping found the local chapter of Comisión Femenil, she later became an aide to Art Torres, the longtime Democratic state legislator. Years later, Molina would defeat Torres in the 1991 campaign for the First District county supervisor seat.

Before running for public office, Molina was a recruiter for the White House personnel office under President Jimmy Carter, and served as an aide to Democratic Assemblymember Willie Brown.

With her victory in 1982 as the first Latina elected to the California legislature (representing the 56th State Assembly District), Molina disrupted what at the time had been a Latino boys’ club. She defeated the better-funded Richard Polanco, who had the backing of the political establishment.

During her time in the Assembly, Molina became involved with Mothers of East Los Angeles, a group that successfully fought plans to build a prison in East L.A.

In 1987, Molina was elected to the L.A. City Council in the First District, where lines had been redrawn to better represent the city’s Latino voters in northeast and northwest L.A. Four years later, after the Latino-majority First Supervisorial District was created by a federal court in response to a voting rights lawsuit, she won that seat, too.

A breakthrough for historically excluded Latino voters

“Gloria Molina was very critical in Latino political history given how she won the council race and then the supervisorial race,” said Fernando Guerra, director of the Center for the Study of Los Angeles at Loyola Marymount University. “She won both of those elections immediately after they were redistricted … because of lawsuits. And so she was the manifestation of very long political and legal battles to have equitable representation of Latinos.”

Before this, he said, Latino voters were largely excluded, their power diluted by how district lines were drawn.

“She's the one who broke that,” said Guerra, an honorary life trustee of the board of LAist’s parent company, Southern California Public Radio.

Molina’s First Supervisorial District, which stretches from downtown and northeast L.A. into the San Gabriel Valley, includes historic Latino working-class hubs like Boyle Heights, El Sereno, East L.A. and Montebello.

Guerra said it was during Molina’s 23-year tenure on the county board that she had the most direct influence on local communities.

“Being one out of five, people had to listen to her,” he said. “They had to listen to that authentic community voice, and that's where she really made a difference.”

‘The worthiest of adversaries’

Former Board of Supervisors colleague Zev Yaroslavsky remembers Molina as “the greatest ally you could have when you were on the same side — and she was the worthiest of adversaries when you were on opposite sides. She was ruthless.”

Yarovslavsky, a fellow Democrat, served alongside Molina on the county board for a decade, until both stepped down in 2014.

While they didn’t always agree — for example, on Molina’s push to add extra beds to the new L.A.-County-USC hospital — Yaroslavsky said Molina’s stubbornness came from the right place.

“When Gloria took a position, she didn’t do it because it would serve her political interest,” he said. “She did it because she thought it was right” and because she was acting on what she heard from the community, Yaroslavsky said.

“She did a lot of her focus groups, as she used to say, standing in line at Costco,” he said. “And she understood the kitchen table issues probably better than any politician I’ve ever seen.”

As for the county hospital, although Molina lost her initial battle, eventually the county cleared the way for more beds years later.

Molina was also unrelenting in persuading her fellow supervisors to oppose Proposition 187, the 1994 California ballot initiative that sought to bar immigrants without legal status, including children, from public services and schools.

“Many times, when people saw me coming, it was, ‘Oh no, here she comes again, I know what’s on her mind,’” Molina told KCET in a special about the initiative. “Because I was very assertive. I was very aggressive about hopefully getting people to join with me in taking a position against 187.”

That was emblematic of the no-holds-barred style her colleagues remember.

“She was un-intimidate-able,” Yaroslavsky said. “She was unbowed when she believed in something.”

Fighting a prison and pollution, and boosting transit

In the 1980s, before she held elected office, Molina became involved with Mothers of East Los Angeles, a group that successfully fought plans to build a prison in East L.A.

“She knew very early on the detrimental impact of the carceral state, not only on the region, but particularly on the Eastside,” said Sonja Diaz, founding director of the UCLA Latino Policy & Politics Institute, who grew up within Molina’s district in El Sereno.

“One of the things about what Gloria represents is she represents Los Angeles, and she represents a part of the region that has been discriminated against — not just politically, but environmentally,” Diaz said, noting that “five freeways cut across East Los Angeles.”

Molina understood how working-class communities bear the brunt of industrial pollution, said Diaz and others. When it became known that the Exide battery recycling plant in Vernon was contaminating surrounding neighborhoods, Molina led efforts to have the county shut it down.

Another key Molina legacy was her push to ensure L.A.'s growing public transportation network made it to the Eastside, said County Supervisor Hilda Solis, who succeeded Molina in the First District.

“During the time that she was serving, she helped to push through the East L.A. Gold Line,” Solis said. “And that was really powerful, because we had no mass transit rail system here in our area … It meant so much for people that were so dependent on bus ridership.”

Other rail lines to the west had been in place for some time, Solis said, but they did not connect to the working-class Latino neighborhoods to the east, where many of those bus riders lived.

“So we're talking about equity, you know, really combating racial injustice — because we should all be able to benefit from taxpayer dollars,” Solis said.

Promoting culture, pushing a food truck crackdown

As a supervisor, Molina worked to elevate Mexican and Mexican American culture, helping create La Plaza de Cultura y Artes, the Mexican American museum and cultural center in downtown L.A.

She also helped save an iconic roadside structure in East L.A. known as The Tamale building.

Molina did catch flak for proposing a crackdown on food trucks that the supervisors passed in 2008, with steep fines and even criminal penalties for those who parked in one spot for more than an hour.

As Molina explained then to TIME magazine, "The businesses don't appreciate [the taco trucks] down in front. And some of the residents consider it annoying to have the trucks out until midnight or two in the morning. We're trying to create a better and more livable community."

The rule was thrown out by a judge, and the county did not appeal.

Influencing future leaders

Solis, who grew up in La Puente, also in the First Supervisorial District, was still a student when she first learned of Molina. She said she considered her a role model.

“Where people always try to place Latinas in very marginal positions, she was out there, pushing the envelope, cracking that glass ceiling and opening it up for other women,” Solis said.

Diaz, with the UCLA Latino Policy & Politics Institute, remembers hearing about Molina from her activist parents when she was growing up in El Sereno.

“As a little girl, someone who identifies as a Chicana, Gloria Molina's political career made clear to me at a young age that Latinas could not only lead, but that they could be powerful,” Diaz said.

“She's leaving a legacy where Latinas now are the majority of the Latino Legislative Caucus,” she added.

Among the L.A. politicians whose careers Molina supported is U.S. Sen. Alex Padilla, also a child of Mexican immigrants. Padilla was elected to the L.A. City Council in 1999 and served alongside Molina before she won her county seat.

“She was a legend long before my first run for Los Angeles City Council,” Padilla said. “But really, to be elected to the board of the largest county in America, with all the power and opportunity that comes with that position, was a big, big deal. By the time I ran for office myself, I knew she was a force to be reckoned with.”

While Molina dedicated herself to local service, her influence had a far bigger reach, according to Guerra of the Center for the Study of L.A.

“She opened up politics not only for Latinos, not only for women, but for populist progressive voices,” he said. “Today, after the ‘22 election, we saw a lot of progressives get elected. But it started with Gloria Molina. Now, some of those progressives might not consider Gloria progressive enough, but if it wasn't for her opening up politics to the populist … approach, which then became acceptable, many of these progressives would not be in the position that they are today.”

Proud of ‘mi gente’ and ‘the work we did’

Antonia Hernández, who went on to serve as president and general counsel of MALDEF, remained close to Molina, who joined her at the California Community Foundation as the nonprofit’s chair in July 2021.

“She's my best friend,” Hernández said in an interview after Molina announced her terminal cancer. “She's my boss … She's a fantastic cook. She is a world-renowned quilter.”

Gloria Molina, Master Quilter

Besides all her political accomplishments, in 2011 Gloria Molina co-founded “The East Los Angeles Stitchers,” known as TELAS (the acronym means “fabrics” in Spanish). The goal was to provide a space where Latinas interested in the art form could connect and learn from each other.

In the Cal State Fullerton oral history, Molina said if she was angry about something that had happened during her day, “I would go home … and I would spend two or three hours in my sewing room quilting. It was relaxing and comfortable and it brought me back the kind of peace of mind that I needed to go in and slay the dragon the next day.”

Molina once presented Padilla with his own quilt, which he described as “about five by five, a whole lot of red, white, and blue.”

In her statement revealing her cancer, Molina said, “You should know that I’m not sad. I enter this transition in life feeling so fortunate.”

She added: “I'm really grateful for everyone in my life and proud of my family, career, mi gente, and the work we did on behalf of our community.”

Reaction to her death

L.A. Mayor Karen Bass:

“Gloria Molina was a force for unapologetic good and transformational change in Los Angeles. As an organizer, a City Councilwoman, a County Supervisor and a State Assemblywoman, Supervisor Molina advocated for those who did not have a voice in government through her pioneering environmental justice work, her role as a fiscal watchdog, and her advocacy for public health. She shaped Los Angeles in a lasting way while paving the way for future generations of leaders. As the first woman Mayor of Los Angeles, I know I stand on Supervisor Molina’s shoulders. On behalf of an ever grateful city, I express my deepest condolences to Supervisor Molina’s family, friends and community.”

L.A. County Supervisor Hilda Solis:

Words can’t express the loss of Gloria Molina. She was a beacon of hope to many — including myself. Seeing her break several glass ceilings throughout her public service career inspired me to follow in her footsteps and be of service to our community. I am grateful for her determination to meet the needs of our most vulnerable. It was her fuerza, her force, that residents often overlooked were able to benefit from our safety net.

To honor her life’s work, I introduced a motion back in March to rename Grand Park to Gloria Molina Grand Park. A park for all, she fought incredibly hard to transform a once cement concrete jungle into a creative green space for Angelenos. I am heartbroken to lose a champion for Latinos, for mujeres, and for the Eastside. While she may no longer be physically with us, we will forever feel her impact. My prayers are with her loved ones during this heartbreaking time. May her soul Rest In Peace.

L.A. County Supervisor Kathryn Barger:

Gloria is one of the strongest women I’ve encountered in my 30+ yrs of county service. She was the 1st to do many things for [L.A. County]1st to advocate for people who had little confidence in government, 1st to give our local immigrant residents a voice.

L.A. County Supervisor Janice Hahn:

It takes courage to be the 1st woman in the room and Gloria was the 1st woman and 1st Latina in nearly every room she was in. She didn’t just make space for herself-- she opened the door to the rest of us. Women in politics in LA County owe a debt of gratitude to Gloria Molina.

L.A. City Council President Paul Krekorian:

Like all who knew her, I am both saddened by the passing of Supervisor Gloria Molina and also grateful for the incredible transformative contributions she made to the history of our State and our City ... she was a fearless and relentless champion who never forgot – and never allowed anyone else to forget – the needs of the neighborhoods she served. Her legacy is everywhere around us ... We should be grateful for the time she spent among us, and for all she did to make Los Angeles a better, more inclusive place for all of us, and for generations yet to come.

Frank Stoltze and Rebecca Nieto contributed to this story.

Updated May 15, 2023 at 7:37 AM PDT

This article was update with reaction to Molina's death.