This story is free to read because readers choose to support LAist. If you find value in independent local reporting, make a donation to power our newsroom today.

Noemí Cruz

Noemí Cruz

Pico-Union • Age 35 • Full-time parent

Lives with Faustino (husband), Naín (10), Abimelec (8) and Melquisedec (1)

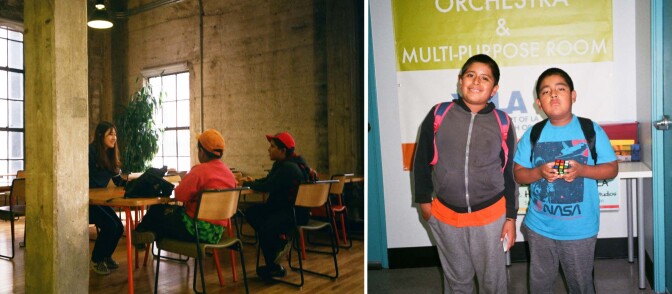

“My two sons Naín and Abimelec are there, one practicing on his viola and the other on his guitar. They are in a music class called Hola. They start without knowing anything about music. They lend out the instruments. You don’t have to pay for the instrument or anything like that. My oldest son, Naín, is learning viola and the younger one is in a beginner’s class, learning about different genres of music and things like that."

About Parenting, Unfiltered

We gave point-and-shoot film cameras to 12 Southern California parents of young children and invited them to document their lives in the Fall of 2019.

Join this group of families, from South Los Angeles to the San Fernando Valley and San Bernardino, as they show us what parenting really looks like, through their eyes.

“About CoachArt, I was able to apply for my son because he has a condition [autism]. All the kids that I’ve seen there are survivors of cancer or they have some kind of medical condition and everyone applies for this program. Thanks to CoachArt, my son is in guitar classes.”

“Oh my God. They tell me, ‘You shouldn’t even go out in the street anymore because everyone says hi to you!’ A lot of people know me because I am always coming and going. Sometimes you don’t see many people coming and going or that are involved, or that you see in the street, or who speak."

I’ve lived here in Pico-Union for more than 10 years. I feel like the community is safe, I feel like it’s mine. In other areas there isn’t as much support as there is here. Around here there are stores very close by, centers for shipping packages overseas. There are a lot of resources.

“[When my son] was nearly 10 months, I started to get involved in Magnolia Place Children's Bureau. A lot of people then told me, ‘Oh, I’ve seen you all over the place. We want to invite you to KIWA [Koreatown Immigrant Workers Alliance].’ OK, so I went to KIWA. After that, I went to IDEPSCA [El Instituto Educación Popular del Sur de California]. IDEPSCA works to support day laborers. They also work with domestic workers, how to empower them to know their rights. We do outreach all over the place and we have a women’s group called ‘Mujeres en Acción.’”

“When my kids started [at PACE, an early childhood program], they gave me a packet of resources. But I didn’t even know what that was. It’s incomprehensible. I didn’t know how it worked, if things were free or if you had to pay. But then as you begin to get involved, when you go to the resource fairs, you start asking, agency by agency, what they do. You start asking questions.

“I’ve been asked to speak, and I always have looked for resources for other people. Because also, people are afraid to speak up. I no longer am afraid of asking questions. If they ask me something or if it’s in English, I say, ‘OK, I need translation.’ And if they say there’s no translation or something, ‘OK, I’ll leave my number so you can call me when you have someone who speaks Spanish.’”

“I have three clocks, one in each part of my house. Serve them breakfast, attend to the baby, go to school, try to clean … I also have to say, 'what time am I going to sleep?' Sometimes, doing things as a mother, you don’t realize or you aren’t tired, so you just keep going and going with your routine. You don’t realize what time it is, and you need space to rest.

“In front of my house, there’s a pedestrian crosswalk that’s really difficult to cross to take the bus. You have to look around with eagle eyes, looking one way and the other because it’s a crossing of four streets … A lot of people have been hit there. People have died on that crosswalk.“[My son Naín, who has autism], sometimes runs. He doesn’t understand when he can run, and it has always scared me. A lot of times he narrowly missed being hit by a car. Those were really shocking times in my life because I had to run after him. And it happened when I was pregnant, too. People would say to me, ‘Your baby is going to fall out!’”

They always like to be in the bus stop because most of the stops have a button to push and it tells you how many minutes until the next bus. They always, especially the older one, since he never has a watch, he always says, ‘Look here! I’m going to see when the next bus is coming.’

“My older son, the one who has autism, is the one who taught us how to ride the Metro. We never had gotten on the Metro before. He forced us to go on the Metro. Now he knows the Metro lines, the stops, where the emergency exits are… He is really excited to know all the lines.”

In the first photo: “We try to eat together sometimes — we try because I don’t always have time. The baby doesn’t let me eat with them. I have to first feed the baby and then eat with them. Eating together as a family is really important, but sometimes, it’s hard. This time I did eat with them. There’s my plate next to theirs.”

In the second photo: “Here in the kitchen, my son looks happy and is really excited because he knows how to prepare his own sandwich. He tells me, ‘Oh, Mami, I want you to always have ham and cheese.’

‘Do you want sliced cheese?’ I ask him.

‘No, that’s OK. I can cut it.’ And there he goes, struggling to cut it, even if he cuts it into tiny pieces, but he does it. He knows how to make his own sandwiches. And I get emotional, too, because he’s now more independent.”

“This is a day that I left the baby with his dad. My husband likes it because the boys, my older sons, didn’t grow up with him, well, not as close as they are now. [My husband] had two jobs when they were growing up. When they were the age the baby is now, they never would stay with their dad. They would be screaming and crying! So the difference with the baby is that he does stay with his dad."

They can bond more, and [the baby] knows that if I leave him with [Dad], he is safe.

“In the bus, lots of people tell me, ‘Hey, why do you carry him like that? That’s such a country thing.’ I tell them, I feel like it’s a comfortable way for me to carry my baby. He has me closer. He has more visibility up there.

“I'm the oldest of my brothers and sisters … My mom told me, 'You have to carry your brother because I have to do the wash, I have to make tortillas.' And there it wasn't possible to carry the baby on your back. The kitchens were very small there, too. I would say, ‘OK, fine,’ and I'd carry him. Sometimes, angrily, because I wanted to play. At 8 years old, it's a time where I really wanted to play. But I couldn't!

“I know many friends who say that even though their parents carried them that way, they never carried their brothers or sisters or any of that. And they don't know how to carry [their kids.]”

“The biggest change for me [during the pandemic] was to not have work and have to pay the rent. My husband has been without work since the second week of March…

“It’s a challenge, but also, I think it’s also an opportunity for rest. When [my sons] were growing up, he was working all the time, from morning until night. Now I am taking this as an opportunity to spend time together and enjoy ourselves at home. And to just be at home, because my life has been to be out and about going to all of my sons’ programs, and now they are all on Zoom.”

“A lot of people are calling me. It’s pretty surprising, because sometimes my phone is going off all day. Sometimes I have to charge it two times because, ‘OK, there’s a call, OK, now a text.’ When I have resources, I share them by Messenger. Sometimes I’m up at 9, 9:30 at night, looking for information.

“People ask me, ‘Oh, I don’t have enough money for rent. I’ve heard that there are resources for rent. Where can I get more information?’ And I have to look for the information, the phone number, all of that. Or, ‘The bills are piling up. Where should I go?’”