This story is free to read because readers choose to support LAist. If you find value in independent local reporting, make a donation to power our newsroom today.

LA’s first 'community solar' project of its kind is online. What it means for clean energy

On the roofs of two unassuming Extra Space storage buildings in Pico Rivera, an array of solar panels is helping nearby families save money on their bills, while also providing a model for the future of “community solar” in urban areas across the state.

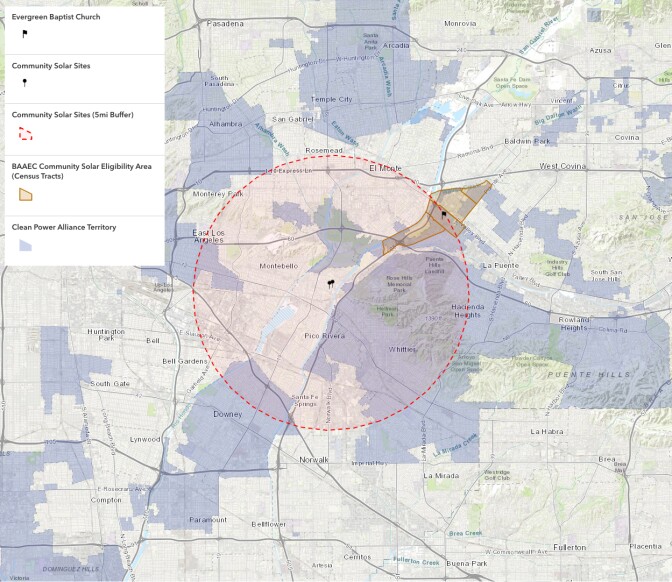

The projects came online in February — nearly 400 low-income households in the Bassett and Avocado Heights neighborhoods in the southeast San Gabriel Valley are subscribed, receiving a 20% discount on their electricity bills.

“Communities like Bassett and Avocado Heights are some of the most pollution-burdened communities in the area,” said Amy Wong, program director with nonprofit Active San Gabriel Valley, which led community outreach for the solar project. “These communities deserve energy justice, and through this project, we're able to do that.”

The unincorporated communities have long dealt with pollution from surrounding freeways, a battery recycling center and the former Puente Hills landfill.

The community solar bill savings program is part of a broader effort in the area to expand access to cleaner energy, including pilot programs installing rooftop solar and battery storage, induction stoves and heat pump water heaters.

What is community solar?

California has mostly focused on building huge solar fields out in the desert, or putting panels on top of single-family homes. But the state has lagged when it comes to “community solar” — small to moderately-sized solar projects that can be installed by developers, governments and individuals or businesses in spaces such as parking lots, warehouse rooftops and empty lots.

Community solar systems work by a process called “virtual allocation,” which means that when you sign up for the program, your bill gets attached to a specific community solar project site near where you live (though not always). It’s essentially a subscription service that allows eligible customers to receive a credit on their monthly utility bills.

Advocates say community solar is a promising way to expand access to cleaner energy for those who don’t own their own roofs or otherwise can’t put solar on their rooftops, such as renters, who make up more than half of L.A. County residents.

How the Bassett-Avocado Heights project works

The project was built by solar developer Pivot Energy, which leases the roof space from Extra Space storage. They then sell the power that’s generated — about 600 kilowatts — to the Clean Power Alliance, which provides energy to 38 communities across Los Angeles and Ventura counties. It’s one of the largest clean energy providers in the state. The Clean Power Alliance ships the electricity to consumers via Southern California Edison lines.

The state then reimburses Clean Power Alliance for the cost difference between a large-scale project and these more expensive, smaller-scale projects, as well as the 20% bill discount, primarily with cap-and-trade dollars.

The households subscribed to this particular project have to already be on SCE’s discount rates. So with the additional 20% off their bills, the households are saving more like 40%.

“It is an example of a successful, equity-focused community solar system in California,” said Robert Cudd, a research analyst and PhD student at UCLA's Institute of the Environment and Sustainability, who studies community solar development in California.

This project took more than five years to develop, and was proposed and orchestrated by local nonprofit the Energy Coalition. Such projects have not taken off in California largely because they're more complicated to design and it's a lot more expensive to develop solar in urban areas.

“The cost to build these smaller projects is at least double that of the large-scale projects, and often much more than that,” said Ted Bardacke, chief executive of the Clean Power Alliance.

But this project penciled out because of a state grant.

“ We don't normally depend on grants to supplement income,” said Charles Tompkins, director of contracts for Pivot Energy.

Tompkins said it’ll take legislative change to make projects like this more appealing to developers. He pointed to a bill now working its way through the California Legislature — AB 1260 — that has broad support from the industry.

The limitations

Active San Gabriel Valley’s Wong said the bill discounts are meaningful to participants, but rising electricity rates are softening the effect.

“For programs like this, it's important for electricity to be affordable year round, no matter how much they use the electricity,” Wong said. “ With community solar, I see it as an essential part of empowering community members to generate electricity locally, and to be able to see that discount is really important for low income communities because of higher costs in living in general.”

With community solar, I see it as an essential part of empowering community members to generate electricity locally.

There’s also the challenge of the so-called “cost-shift,” a major debate right now at the state level as the California Public Utilities Commission moves to slash rooftop solar incentives. The argument is that subsidies for solar are shifting costs to consumers who don’t have solar — because ultimately someone needs to pay for those discounts.

“ These types of programs to be successful do require a subsidy from someone, whether it's the state or other ratepayers in order to scale now,” Bardacke said.

He noted that community solar is largely not subsidized by rates, but rather the state’s cap-and-trade program, which is funded by polluting industries. And much of what’s causing rising rates is hardening the power grid against wildfires and building it out to support higher electricity demands.

Advocates argue that more rooftop and community solar can lessen the need for that buildout.

“Community solar is a promising approach to building more capacity in a less materially intensive way,” Cudd said. “Although I would not say that anyone has settled the political controversy of how much cheaper or better it would be.”

What’s next?

The project is the first of its kind to go online as part of the Clean Power Alliance’s portfolio — and there are 12 similar projects in the pipeline, Bardacke said. Those projects will provide bill discounts for low-income households in Carson, Commerce and Hawthorne.

All of those will be on warehouses owned by Prologis, a major supply chain real estate developer.

“They're basically selling us all of the power and therefore generating additional revenue from their own rooftop,” Bardacke said.

More coverage of community solar

The state’s grid operator, the California Independent Systems Operator, or CAISO, acknowledged in a recent blog post that the Bassett-Avocado Heights project is a promising model for expanding community solar in urban areas.

“Over the years we have seen several developers starting down the path … become intimidated by requirements and approval processes needed at multiple levels before reaching commercial operation,” said Jill Powers, the ISO’s Demand Response and Distributed Energy Sector manager. “We are so excited to see this project come online and hope this will become an example to others that the pathway to markets is open.”

However, the Trump administration’s tariffs, as well as potential cuts to clean energy tax credits are concerning developers and could slow the rollout of more community solar projects.

“Solar and storage are the fastest, most affordable energy generation, and we need these technologies to support a strong energy economy,” said Tom Hunt, chief executive of Pivot Energy, in a statement on the potential of ending clean energy credits.