This story is free to read because readers choose to support LAist. If you find value in independent local reporting, make a donation to power our newsroom today.

Why Mainstream Success Was A Double-Edged Sword For The First Black Movie Star

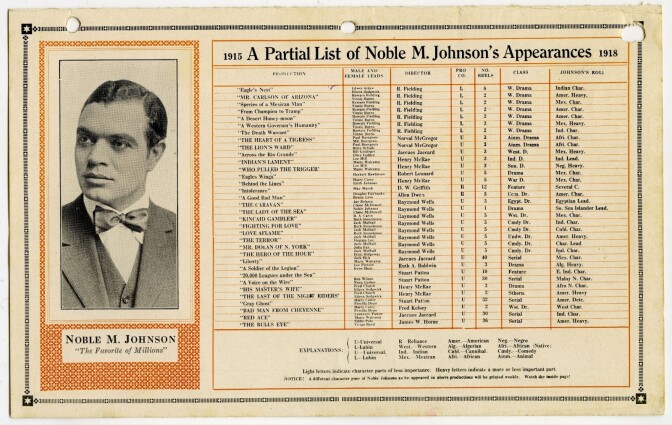

The list of things that makes Noble Johnson remarkable is almost comically long. He was the first Black matinee idol and the first Black person to write a Hollywood movie: The Indian's Lament (1917). He’s also believed to be the only Black actor to play a starring role in a silent-era film: Universal’s The Lady from the Sea in 1916.

Throughout his long career in Hollywood, Johnson acted alongside some of the most famous actors in film history, including: John Barrymore, Douglas Fairbanks, Anna May Wong, Bette Davis, John Wayne, Gary Cooper and Bob Hope. He was in the original King Kong (1933), The Mummy (1932), Moby Dick (1930), The Ten Commandments (1923) and 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (1916).

Listen to the latest episode

He was a skilled horseman, makeup artist, and dog trainer. (An article about Johnson from the December 1933 issue of Kennel Review notes that he taught a deaf English bull terrier to understand hand signals — a skill he’d learned from Mexican sheepherders he’d worked with in his home state of Colorado.)

About Lincoln Motion Picture Company

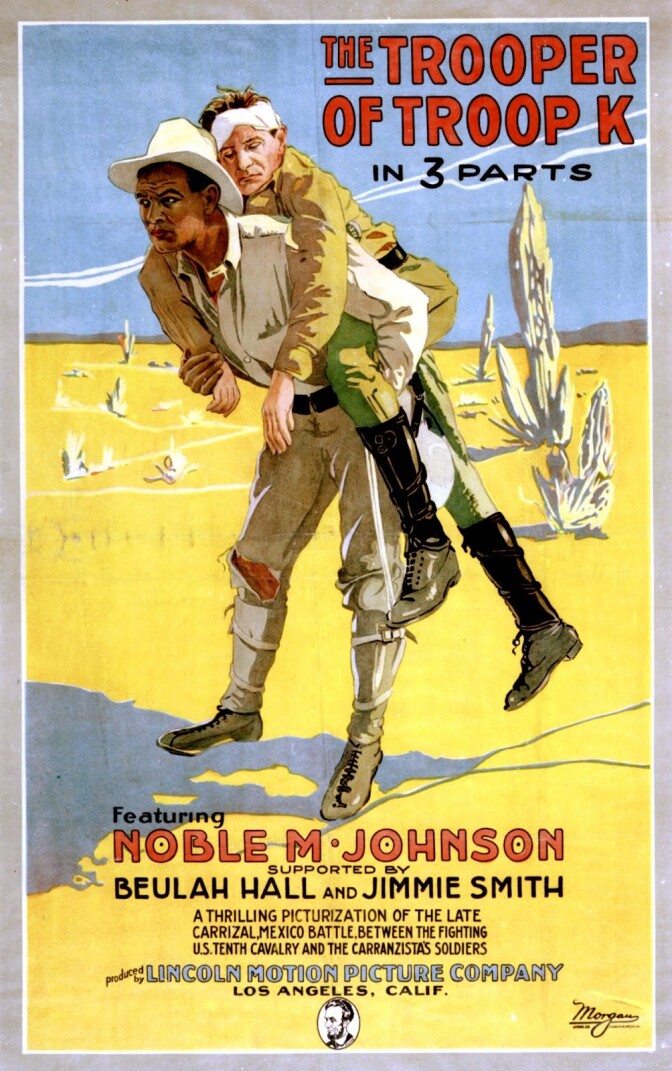

Johnson also started his own independent studio in Los Angeles, the Lincoln Motion Picture Company. History was made just last year, when a film scholar discovered a fragment of one of their earliest films — 1916’s The Trooper of Troop K — embedded within another Lincoln Company film from 1921.

The company was formed in Los Angeles in 1915 by Johnson, who served as president, and a small group of other founding members — Black and white — while Johnson was also working as an actor for Universal. Their mission was to make so-called “race films”: movies intended for Black audiences that featured Black actors in roles that weren’t stereotypical caricatures (unlike other films made by white filmmakers at the time) and that weren’t played by white actors in blackface.

What now stands as the oldest surviving footage of a film produced by a Black film company is from The Trooper of Troop K (a discovery that was made in 2021 by Cara Caddoo, Indiana University cinema and media studies scholar).

Prior to Caddoo’s identification of the footage, and its verification by the Library of Congress, film scholars believed the oldest surviving films produced by Black filmmakers were from the 1920s.

Why it was popular, but short-lived

The Lincoln Motion Picture Company’s films were popular, and they played in theaters across the country (thanks to Noble’s brother George P. Johnson, who marketed and distributed them), but Caddoo told The Academy Museum Podcast host Jacqueline Stewart, the company’s run was short-lived.

“The big Hollywood companies that were doing the same thing, they were struggling. It was just really hard to make a profit off of the productions. And especially enough profit that they could continue making more productions,” says Caddoo.

There was also the flu pandemic of 1918, which resulted in the shuttering of many movie theaters and made distributing films even more difficult and costly.

But another unique problem for the Lincoln Co. was the success Johnson found being cast in films for studios like Universal, playing characters of various races.

“On one hand, Noble is playing all of these Black leads in the Lincoln Motion Picture Company films,” Caddoo says. “But at Universal where he was working as a contract actor, he's playing, Native Americans, he's playing Asians, he's playing Mexicans.”

How Hollywood saw Johnson

At the Academy Museum in L.A., Johnson is featured in an original 1937 issue of The Academy Players Directory, a catalog of photos of actors that for years was published by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences and used by directors, writers, producers and studio heads to cast films.

For the first several years that the directory was issued, including the one on display in the museum, it was racially segregated. But Johnson is included among the white actors.

And while film historian Caddoo says Johnson never “passed” in the sense of denying his Blackness and saying he was white, she also says, “he also just refused to talk about his race altogether.”

George P. Johnson: At Universal, out of 50 pictures, I don’t think he played a Negro part in more than about three. As a great makeup artist, he made up as an Indian or a West Indian or a South American or pretty near anything they wanted to make-up.

Interviewer: But in the Lincoln Company films he played Negro parts?

Johnson: Oh, in the Lincoln Company he played naturally. He didn’t need any makeup, no. Of course we were featuring Negro films, that was our business. But he got in pictures accidentally and made good. He got in all those big pictures, but he didn’t get in there as a Negro, he got in there as an actor.

What happened when white theater owners complained

Then complaints from white theater owners — that Johnson’s Lincoln Motion Picture Co. films were taking business away from their theaters — changed things.

“They complained to Universal,” Caddoo says. “And Universal called Noble on the carpet and was basically like, ‘Are you gonna continue with that work or are you gonna continue with our work?’”

The fact that Johnson was “kind of advertising himself out there as this representative of the Black race,” Caddoo says, also “really complicated Universal's ability to market and to advertise him as all these different kinds of racial types. And it really made it dangerous for Universal, in their minds, [to show] him on screen with white women.”

While all the reasons that Johnson had for leaving the company he founded aren’t totally known, he parted ways with his partners in 1918 and the company shuttered in 1921.

Johnson's impact in Hollywood

Today, though Johnson may not be a household name, the impact he had on Hollywood is undeniable. He had one of the longest-running careers of any Hollywood actor — spanning 1915 to 1950, from the silent era to horror films of the 1930s and comedies in later years. Apart from his groundbreaking work making “race films” with his own company, and creating opportunities for himself and other Black actors, he also used his skills as an actor and makeup artist to originate character types that previously hadn’t existed.

You don't forget seeing him on screen. He's just got this charisma and this ability to kind of take over whatever scene he's in.

“Even though his characters, in many ways, we would see them as problematic today,” says Caddoo, “They're always these standout [roles]. You don't forget seeing him on screen. He's just got this charisma and this ability to kind of take over whatever scene he's in.”

When it comes to Johnson’s legacy, Caddoo says he paved the way for actors who would be described as “ethnically ambiguous” today. “He made space for these other kinds of actors and he made space for other kinds of representations on screen that weren’t legible and that weren't easy to read.”

“And I think that's really important because it really pushes us to think about the complexity of race and also the complexity of what it means to be Black. That there's a much wider range of appearances, of behaviors, of actors who are Black than we typically see on screen.”

How do I find The Academy Museum Podcast?

It's now available from LAist Studios. Check it out wherever you get your get podcasts! Or listen to the second episode of season two on the player above.