This story is free to read because readers choose to support LAist. If you find value in independent local reporting, make a donation to power our newsroom today.

The Story Of How Hundreds Of ‘Aunties’ Came Together To Sew Masks During The Pandemic's Height

When Los Angeles-based performance artist Kristina Wong started a mask-making group early in the pandemic, her first recruits were her Asian American friends. Many had picked up sewing from relatives who had worked in garment shops and laundries, some of the only jobs available to them when they first emigrated to the U.S.

Wong dubbed the volunteers the “Auntie Sewing Squad,” using a cross-cultural term of endearment and deference, while also thinking to herself, what a “sick irony,” she said in an interview with LAist.

“I'm ordering a bunch of Asian women to do this labor that our grandparents or parents never wanted to do ever again because this country, which is the most powerful country in the world, has failed to provide us with masks,” Wong said.

A self-dubbed 'sweatshop overlord'

In keeping with her trademark irreverence, Wong anointed herself the aunties’ “sweatshop overlord,” a moniker that stuck and is now the title of her one-woman show running now through March 12 at the Kirk Douglas Theatre in Culver City.

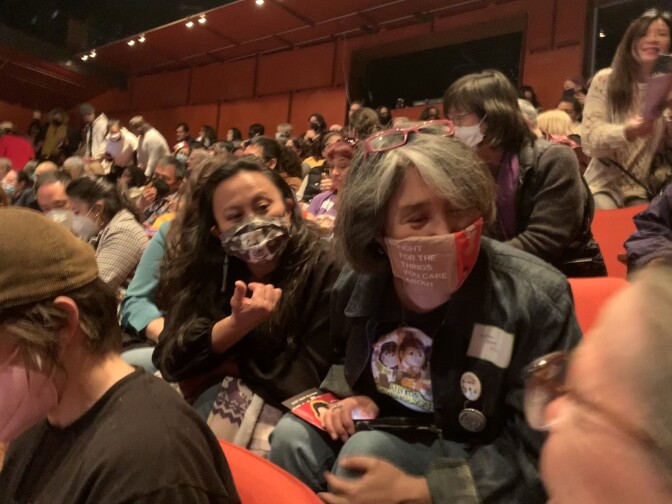

Several dozen aunties came from all over California to attend a recent show. Many had never met in person before and their gathering had the vibe of a family reunion as they excitedly pulled each other in for hugs and posed for group selfies.

The women addressed each other as “auntie,” to Preeti Sharma’s delight.

“Growing up, in the South Asian context, aunties are sometimes gossip mongers who watch and surveil you,” said Sharma, a professor of American Studies who cut fabric for the group from her home in Palms. “But we just had so much fun playing with these terms and making it work for our community.”

The aunties had bonded over Zoom meetings and texts and talked each other through the horrors of the pandemic: the mass COVID-19 deaths, the police killing of George Floyd, and the rise in anti-Asian violence.

“We were like living history and living it together,” said Jenni Kuida, a grants manager from Culver City, who picked up sewing again after 35 years to make masks. “That was something that will always stay with me.”

Finding humor in a dark time

The aunties found light where they could, starting with the discovery that their group’s acronym, was A.S.S.

They laughed at their desperate hunt for fabric and elastic that had become scarce during the pandemic.

"In general, people were sourcing fabrics from old sheets," said Gayle Isa of Lincoln Heights, who produced 1,000 masks with her daughter, who was 8 at the time.

She recalled how one woman offered up her son’s clean underwear.

That drew a firm "no" from Wong, Isa and other members recalled, laughing.

Surprising generosity

Inside the theater, the group filled entire rows as the lights dimmed and Wong walked out on stage to tell their story dressed as her "Sweatshop Overlord" alter ego. A bandolier made of spools of thread hung off her chest and pin cushions were strapped to her arms.

Wong often called out aunties out by name. "Auntie Lelani" cut up her hula costumes to make masks headed to the Navajo Nation. "Auntie Jenni" took scraps from her childhood clothing to make masks for migrant children at the border.

“This doesn't feel like thankless, lonely sacrifice when I am not the only one willing to cut the clothing off my back to make this work happen,” Wong said, looking into the audience.

In the dark, aunties clasped hands and fought back tears.

Show named Pulitzer Prize finalist

The show, a Pulitzer Prize finalist that helped land Wong a $550,000 prize from the Doris Duke Foundation and CAA representation, is in keeping with her tradition of drawing from real-life experiences to make art. Until stay-at-home orders came down in March 2020, Wong had been traveling the state with a play about her election to a neighborhood council in Koreatown.

With Sweatshop Overlord, Wong focused on a facet of human nature she doesn’t usually explore: the generosity of others, and — to her surprise — her own propensity to give.

For several days in March 2020, Wong was sewing masks on her own in her Koreatown apartment for nurses and other essential workers when she soon realized she couldn’t meet the hundreds of requests pouring into her inbox.

On running a 'shadow FEMA' operation

She put out a call for help on Facebook and created the sewing group as “just a little stopgap, until the government stepped in and got those cargo ships from China, [got] them unloaded and [got] masks to everybody.”

Of course, that never happened in any systematic way, and the sewing group became a “shadow FEMA,” Wong said, distributing 350,000 masks to farm workers, indigenous communities and the medically vulnerable.

I want to bring into history that Asian people, we're not just being beat up in the streets. We're not the 'bringers of the virus.' We were actually also stepping up to protect our fellow Americans.

By the time the group retired in Sept. 2021, its numbers had grown to 800 people across 33 states and included “uncles,” nonbinary people and children. Their experience would inspire a compilation of essays called The Auntie Sewing Squad Guide to Mask Making, Radical Care, and Racial Justice.

During their time in the sewing group, some members persevered through COVID-19 and other illnesses.

Wong noted how Asian aunties feared for their safety and that of loved ones, even as they fashioned masks to safeguard strangers.

"I want to bring into history that Asian people, we're not just being beat up in the streets,” she said. “We're not the 'bringers of the virus.' We were actually also stepping up to protect our fellow Americans."

Corrected February 24, 2023 at 8:51 AM PST

An earlier version of this story incorrectly spelled Gayle Isa's last name. We regret the error.