Officials say prison hunger strike leader still in control of Mexican Mafia; The American media's waning interest in the Navy Yard shooting; Is it legal to dismiss jurors based on their sexual orientation?; Starbucks CEO says guns no longer welcome in stores; Does the NFL take taxpayers for a ride?; State Of Affairs: Board of Supervisors, Jose Huizar, and more

Starbucks CEO says guns no longer welcome in stores

Starbucks CEO Howard Schultz announced this week that guns are no longer welcome in its stores.

"Guns and weapons should not be part of the Starbucks experience. And our customers and all of you will be much more comfortable if our customers would not bring that gun into a Starbucks store."

The fact that he said it out loud might be surprising to you latte sippers out there. After all, a Frappuccino, scone and glock don't tend to be in the same place at the same time.

In most states, however, it's completely legal to openly carry a firearm. In the past several months, activists had been meeting at Starbucks with their guns in tow to demonstrate that point. But for a country all too familiar with mass shootings, that right is being tested against people's fear of another fatal event.

Joining us now is Adam Winkler, professor of constitutional law at UCLA, and author of, "Gunfight: The Battle Over the Right to Bear Arms in America."

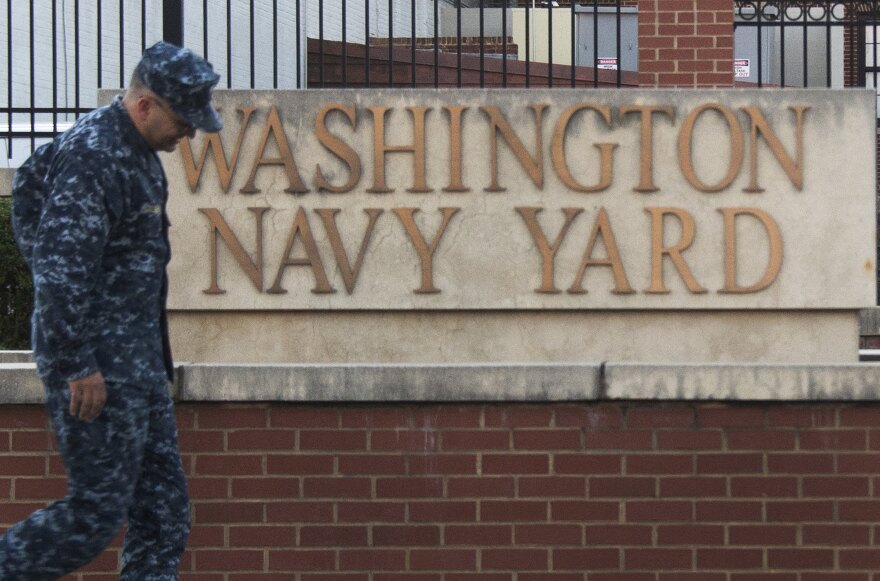

The American media's waning interest in the Navy Yard shooting

The statement that guns are no longer welcome in Starbucks came just two days after the mass shooting at the Navy Yard in Washington, DC. 34-year-old Aaron Alexis killed 12 people before being shot by police.

While the story lead the news on Monday and Tuesday, it doesn't seem to have held the attention of the American public for very long. Paul Farhi, media reporter for the Washington Post, wrote about this in a column for today's paper.

Officials say prison hunger strike leader still in control of Mexican Mafia

This year's California inmate hunger strike was big news. The strike, which began with more than 30,000 inmates refusing meals dwindled to only a hundred or so after a couple of months. But it still drew nationwide attention to the issue of prison overcrowding and solitary confinement.

The strike was orchestrated by a few inmates at the Pelican Bay maximum security prison, one of them was Arturo Castellanos, a convicted murderer who has been held in isolation at Pelican Bay since 1990.

RELATED: How Imprisoned Mexican Mafia Leader Exerts Secret Control Over LA Street Gangs

Now federal officials have allegedly discovered evidence that Castellanos has not just orchestrated the hunger strike, but is still in a position of control in the Mexican Mafia gang.

The evidence in question? One part seems to rely on a small hand scrawled note known as a "kite" in prison jargon. The feds allege the letter was written by Castellanos and sent to members of the Florencia 13 street gang in Los Angeles:

The document outlines of series of rules, covering how street gangs are to be governed, how drug sales, prostitution and other activities are organized and taxed (with a percentage going to gang leaders behind bars), how disputes are resolved, how Mexican nationals are to be respected and the constant hunt for snitches.

Michael Montgomery, reporter with KQED and the Center for Investigative Reporting who has obtained a copy of this kite, joins the show with more.

View a larger version of this document.

Drug cartels thrive on ultimate consumers: addicts

Drug cartels are doing big business up and down the West Coast. When you travel by freeway, you’re driving a Silk Road of sorts for heroin, meth and cocaine.

This export industry is evolving. Drug experts say heroin is back on the rise, fueled in part by prescription drug abuse. And while the supply side of the business may change, the demand remains strong.

Heavy-duty prescription painkillers have something in common with heroin. They're both a type of drug called an "opiate" and the effect they have on people who get hooked is similar.

One difference? Heroin is usually cheaper and easier to get. That was true for Portlander Kevin Lehl. He said he got hooked as a teen when he was prescribed opiates to treat chronic pain.

"I was in love with it from the very beginning," Lehl said.

He says hunting for pills turned into a full-time obsession, and he eventually made the switch to heroin. It was everywhere.

"Once you're kind of like in this opiate world, you kind of know people that know people that know people," Lehl said.

Lehl said he's been clean since the beginning of the year. He's now taking community college classes in hopes of becoming a drug counselor. He's also found a new part of town to live in.

There’s an old joke that there’s a coffee shop on every corner in Portland. For Lehl, heroin was actually more convenient to get than coffee.

"In my old neighborhood, there's probably like seven people within a five block radius that sells heroin and pills," he said.

But unlike the fiercely competitive coffee market, drug experts say heroin dealers don't really need to advertise.

"They don't push their drug because this drug sells itself," said Lee Hoffer, an anthropologist who teaches at Case Western Reserve University in Ohio. His specialty is the heroin market. And he studies it the old-fashioned way. He just walks up to drug dealers and starts asking questions.

Hoffer said drug dealers generally rely on word-of-mouth advertising. Think of it this way: You move to a new town, "You're going to ask your friend, where's a good mechanic? Or what doctor do you use? This is how people find heroin dealers."

And after awhile, those dealers and other users become part of your social circle. That's what happened to Portland heroin user Linda Wickerham.

"Everybody kind of watches out for each other because they know what it's like to be sick when you don't have your heroin," Wickerham said. "And so even if I have a little bit, I'll share it with my other two friends because I know what it's like being sick."

Wickerham didn't come to heroin through prescription painkillers. An acquaintance offered her a dose about four years ago.

"I tried it once and have been on it ever since," she said. "I can't stop. It's hard."

I met her at a clinic run by Oregon Health and Science University that tries to help people addicted to opiates. Wickerham said she's come here about a half-dozen times in an effort to shake the habit. But it’s not going so well.

I ask her when was the last time she used.

"Today," she said. "Today I used."

Wickerham said she'd really like to quit. But going without heroin has proved to be just too difficult.

"If I don't use I'm going to be sick and that's a whole new different ballgame there," she said. "You can't even imagine what it's like when you don't have your heroin how sick you get."

And in a nutshell, that's why the business of selling heroin is so brisk. Dr. Amanda Risser of OHSU said addicts routinely tell her that trying to quit involves a willpower they just don't possess.

"The withdrawal syndrome is so awful and so, I mean when folks describe how they feel when they're in withdrawal, people really do feel like they're going to die," RIsser said.

But for many users, the withdrawal symptoms aren't the only thing standing in the way of quitting. They actually like the drug, said Caleb Banta-Green. He's a researcher at the University of Washington's Alcohol and Drug Abuse Institute.

"People begin wanting heroin more than they care about food and drink and love and things like that," he said.

And Banta-Green said dealers know how to tap into that addiction. Like any good salesperson, they offer discounts to keep their best customers happy.

"The issue with heroin is that most people who use heroin use pretty regularly," Banta-Green said. "They might use easily 20 days out of the month, so having a regular steady customer might be worth selling for a little bit less, because you're really working on getting repeated sales."

For Wickerham, the worst part about her addiction is the guilt she feels about allowing the drug to separate her from her family. She said she rarely sees her two daughters and her grandson because using heroin has thrown her life into chaos.

"People say 'you must not want to be with them that bad because you're still doing heroin,'" Wickerham said. "But it's not like that. It's not that easy. But for me that is my rock bottom, not being with them every day. Because either I'm by myself or with my friends that do heroin. And that's not the kind of life I want."

But it's the kind of life heroin producers and dealers want her to have. Because Wickerham and countless other addicts are the ultimate consumers: The kind who can’t stop buying the product even when they don't want it anymore.

Yudof prepares to leave UC Presidency

The UC Board of Regents this week voted to renovate the Blake House, a now empty Bay Area mansion that has traditionally been home the UC president. The group approved the budget for $620,000.

UC Regents are meeting this week, as President Mark Yudof departs after five turbulent years. The California Report's Ana Tintocalis looks back on his tenure, beginning with a visit to the UC Berkeley campus.

Is it legal to dismiss jurors based on their sexual orientation?

A potential juror cannot be removed from a jury because of race or gender, but what about sexual orientation? It's a question the 9th US Circuit Court of Appeals is now considering in the wake of an antitrust dispute between the drug companies Smith Kline Beecham and Abbott Laboratories.

Here to tell us about the case and the questions it raises about jury selection is Vik Amar, associate dean for Academic Affairs at the UC Davis School of Law.

Actress Jenna Fischer takes the stage in 'Reasons To Be Pretty'

Actress Jenna Fischer is perhaps best known for her role as Pam Beasly Halpert in the hit TV show "The Office."

The show came to an end earlier this year and now Fischer is back to her theatrical roots, taking to the stage in an LA Theater Works production of Neil LaBute's play "Reasons To Be Pretty."

RELATED: Get tickets and more information about the show

State Of Affairs: Board of Supervisors, Jose Huizar, and more

Time for State of Affairs, our look at politics and government throughout California with KPCC political reporters Alice Walton and Frank Stoltze.

The Board of Supervisors made news this week with the announcement that more than 500 jail inmates would be sent to firefighter camps. Why is the county doing this?

It seems we are always talking about an election here and this week is no exception. There were two special elections this week to fill state seats that were vacated when politicians were elected to the Los Angeles City Council. What's the latest with the state Senate and Assembly races?

Over at City Hall, a panel is underway to look at allegations that Councilman Jose Huizar sexually harassed one of his staffers. This is a confidential process, but is the public going to find out what's happening here?

Finally, both L.A. county and city have thrown their support behind an effort to bring the Olympics back to Southern California in 2024. What are the chances this will become a reality?

Adult film actors call for stricter HIV protection

Despite recent reports from several porn actors they've tested positive for HIV, the adult film industry plans to return to business as usual tomorrow after a temporary shutdown. At issue is whether actors are properly protected from the risk of contracting sexual diseases.

In a news conference yesterday, a number of actors argued condoms should be required on every set. L.A. County voters already have passed a law to that effect, and a federal court upheld it last month, but the porn industry has vowed to appeal. Reporter Steven Cuevas has more.

Defense lawyers for AEG rest case in Michael Jackson trial

The Michael Jackson trial may finally be coming to an end. The case is now in its 21st week and lawyers for concert promoter AEG rested their defense yesterday.

To catch us up on this, we're joined once again by Jeff Gottlieb of the LA Times.

'House in the Sky': Memoir of a female journalist held captive in Somalia

Freelance journalist Amanda Lindhout has described her travels all over the world as an innate curiosity to learn. On assignment in rural Somalia in 2008, however, her thirst for travel became a fight for her life.

Four days after her arrival, she was kidnapped by a group of Muslim men who demanded a ransom of $1.5 million from her family in Alberta, Canada. Lindhout was kept in captivity for 15 months, during which time she was tortured and repeatedly raped.

Her new memoir, "House in the Sky" retells her captivity, her survival and her eventual freedom. When we spoke with Amanda Lindhout earlier she began by telling me how the insatiable desire to travel came at an early age.

Excerpt

Prologue

We named the houses they put us in. We stayed in some for months at a time; other places, it was a few days or a few hours. There was the Bomb-Making House, then the Electric House. After that came the Escape House, a squat concrete building where we’d sometimes hear gunfire outside our windows and sometimes a mother singing nearby to her child, her voice low and sweet. After we escaped the Escape House, we were moved, somewhat frantically, to the Tacky House, into a bedroom with a flowery bedspread and a wooden dresser that held hair sprays and gels laid out in perfect rows, a place where, it was clear from the sound of the angry, put-upon woman jabbering in the kitchen, we were not supposed to be.

When they took us from house to house, it was anxiously and silently and usually in the quietest hours of night. Riding in the backseat of a Suzuki station wagon, we sped over paved roads and swerved onto soft sandy tracks through the desert, past lonely-looking acacia trees and dark villages, never knowing where we were. We passed mosques and night markets strung with lights and men leading camels and groups of boisterous boys, some of them holding machine guns, clustered around bonfires along the side of the road. If anyone had tried to see us, we wouldn’t have registered: We’d been made to wear scarves wrapped around our heads, cloaking our faces the same way our captors cloaked theirs—making it impossible to know who or what any of us were.

The houses they picked for us were mostly deserted buildings in tucked-away villages, where all of us—Nigel, me, plus the eight young men and one middle-aged captain who guarded us—would remain invisible. All of these places were set behind locked gates and surrounded by high walls made of concrete or corrugated metal. When we arrived at a new house, the captain fumbled with his set of keys.

The boys, as we called them, rushed in with their guns and found rooms to shut us inside. Then they staked out their places to rest, to pray, to pee, to eat. Sometimes they went outside and wrestled with one another in the yard.

There was Hassam, who was one of the market boys, and Jamal, who doused himself in cologne and mooned over the girl he planned to marry, and Abdullah, who just wanted to blow himself up. There was Yusuf and Yahya and Young Mohammed. There was Adam, who made calls to my mother in Canada, scaring her with his threats, and Old Mohammed, who handled the money, whom we nicknamed Donald Trump. There was the man we called Skids, who drove me out into the desert one night and watched impassively as another man held a serrated knife to my throat. And finally, there was Romeo, who’d been accepted into graduate school in New York City but first was trying to make me his wife.

Five times a day, we all folded ourselves over the floor to pray, each holding on to some secret ideal, some vision of paradise that seemed beyond our reach. I wondered sometimes whether it would have been easier if Nigel and I had not been in love once, if instead we’d been two strangers on a job. I knew the house he lived in, the bed he’d slept in, the face of his sister, his friends back home. I had a sense of what he longed for, which made me feel everything doubly.

When the gunfire and grenade blasts between warring militias around us grew too thunderous, too close by, the boys loaded us back into the station wagon, made a few phone calls, and found another house.

Some houses held ghost remnants of whatever family had occupied them—a child’s toy left in a corner, an old cooking pot, a rolled-up musty carpet. There was the Dark House, where the most terrible things happened, and the Bush House, which seemed to be way out in the countryside, and the Positive House, almost like a mansion, where just briefly things felt like they were getting better.

At one point, we were moved to a second-floor apartment in the heart of a southern city, where we could hear cars honking and the muezzins calling people to prayer. We could smell goat meat roasting on a street vendor’s spit. We listened to women chattering as they came and went from the shop right below us. Nigel, who had become bearded and gaunt, could look out the window of his room and see a sliver of the Indian Ocean, a faraway ribbon of aquamarine. The water’s proximity, like that of the shoppers and the cars, both comforted and taunted. If we somehow managed to get away, it was unclear whether we’d find any help or simply get kidnapped all over again by someone who saw us the same way our captors did—not just as enemies but enemies worth money.

We were part of a desperate, wheedling multinational transaction. We were part of a holy war. We were part of a larger problem. I made promises to myself about what I’d do if I got out. Do something good for other people. Make apologies. Find love. Take Mom on a trip.

We were close and also out of reach, thicketed away from the world. It was here, finally, that I started to believe this story would be one I’d never get to tell, that I would become an erasure, an eddy in a river pulled suddenly flat. I began to feel certain that, hidden inside Somalia, inside this unknowable and stricken place, we would never be found.

Amanda Lindhout discusses her book at Diesel book store in Brentwood on Thursday, Sept. 19

Does the NFL take taxpayers for a ride?

It's the most popular, and profitable sport in America. The NFL has the best television deals, and the highest profit margins in professional sports. Total revenues are approaching $10 billion per year.

Yet the NFL itself, under a little known provision in a 50-year-old law, operates as a not-for-profit business. It's exempt from anti-trust laws, and it has a long history of convincing local and state governments to pay for much or all of the cost of constructing stadiums.

Sports writer and commentator Gregg Easterbrook loves the game, but finds the way the NFL operates to be distasteful. He's written about this in a new book, The King of Sports: Football's Impact on America. A section of it has been excerpted and published by The Atlantic.

Case in point: Two years ago, as the state of Minnesota was facing a more than one billion dollar deficit, it awarded the owners of The Vikings more than $500 million for a new stadium.

Easterbrook said the NFL and its owners (most of whom are billionaires, he notes) argue that stadium construction and the ongoing operation of football teams create economic opportunity. Easterbrook counters that many studies show the benefits of any economic boost almost never equals the amount of taxpayer money invested.

The tradition of soliciting taxpayer money to build football stadium goes back to the 1950's, and the beginnings of what became the NFL, said Easterbrook. "The owners of those teams were not billionaires," he says, and often needed public support to build sites for the clubs to play in.

"Now, there's money flowing through the NFL like crazy," he said, "but we still use this 50-year-old idea that stadiums are like libraries or colleges and cannot exist unless the public supports them."

Easterbrook believes the real culprits in what he sees as a fleecing of taxpayers are the elected officials, in the U.S. Congress, state houses and city councils that cut deals with owners. He said he hopes the citizens of Los Angeles will reject any bid to bring an NFL franchise to the city that includes any form of taxpayer contribution.

His solution to the public financing of football stadiums: change the rules regarding television broadcasts, which are at the heart of the NFL's money-making machine. Easterbrook noted that teams make most of their money by copyrighting game performances, and licensing broadcast rights.

Just change the law so that games played in publicly funded stadiums can't be copyrighted. "The NFL will immediately negotiate to pay the full and proper cost of all its stadiums," said Easterbrook, "and then that problem will solve itself."

Vote may change status of ride-sharing services in California

Rideshare services, like Lyft and Uber, have quickly gained in popularity in Los Angeles. They have that "hip" factor working for them, but all along they've been rogue operators.

KPCC's Ben Bergman has been following a vote going down today that could change their status in the state.

RELATED: California could be first state to regulate ride-sharing