Imagine for a moment if the population of a group of people dropped 80 percent in less than three decades.

A mass die-off, or a mass extermination?

The latter is what UCLA assistant professor of history, Benjamin Madley says happened to California's native populations. The kicker? The mass extermination was state-sponsored with taxpayer dollars.

Madley wrote about this in his new book, "An American Genocide: The United States and the California Indian Catastrophe," and shared his findings with Take Two's A Martinez.

What tribes were here and how did they co-exist with others who called California home?

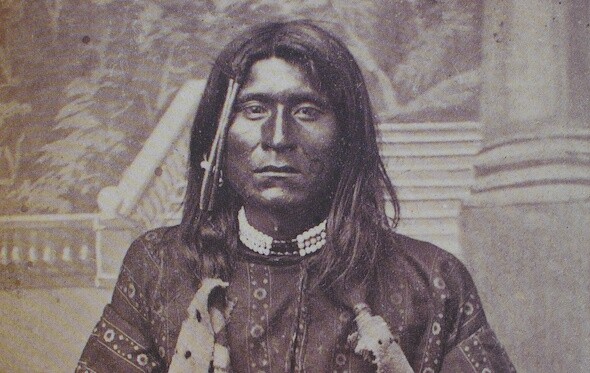

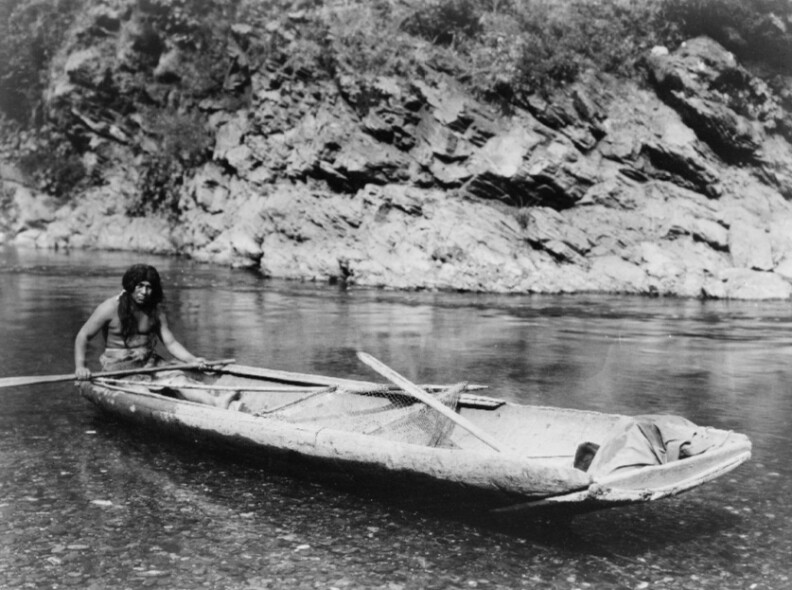

There were many different tribes here in California. In the northwestern corner of the state, there were the Tolowa; they were people who hunted and fished. They had 60-foot long redwood dugout canoes. Down in the southeast portion of the state, there were Quechans, who farmed along the banks of the Colorado River. And they traded with each other; there were extensive trade networks that roughly follow the lines of today's interstate highways.

California became a state in 1850. Did statehood change things?

Statehood did change things. California's legislature first convened in 1850, and one of its initial orders of business was banning all Indians from voting, barring all Indians with one-half of Indian blood or more from giving evidence for or against whites in criminal cases, and then denying Indians the right to serve as jurors. California legislators banned Indians from serving as attorneys, so in combination, these very laws shut Indians out of participation in and protection of the state legal system. So this amounted to a virtual state-sponsored grant of impunity to those who attacked them.

It almost was if California's legislature decided to declare war on the native population ...

I think it's not an exaggeration to say that California legislators established a state-sponsored killing machine. California governors called out or authorized no fewer than twenty-four — that's two dozen — state militia expeditions between 1850 and 1861, which killed at least 1,340 California Indians. And state legislators put the power of the purse behind this project. They passed three bills in the 1850s, which raised up to 1.51 million dollars to fund these operations. These militia expeditions helped to inspire vigilantes to kill at least 6,460 more California Indians during this same period.

You mention how the State of California and the US Government have not called this genocide. Why not?

Frankly, there's a lot at stake. When Presidents Ronald Reagan and George H.W. Bush recognized the forcible relocation and internment of some 120,000 Japanese-Americans — many of them Californians —during World-War Two, this then led to compensation. Congress has now paid out over $1.6 billion dollars to these Japanese-Americans and their heirs [...] And there's also the legacies that are all around us. Should we stop commemorating the supporters and perpetrators of this genocide: people like Peter Burnett, Kit Carson, John C. Freemont. And there's also the question of education: will the genocide against California Indians join the Armenia Genocide and the Holocaust in public school curricula or public discourse? So there's a lot a stake in acknowledging genocide.

Press the blue play button above to hear this interview.

(Post has been updated.)