They called it the Glass House, but it was anything but transparent.

When Parker Center opened 62 years ago, it was hailed as a monument to modern, efficient, policing, reliant on radio cars, IBM punch-card-sorter machines, helicopters, the chemistry and physics of mid-century forensic science. Its six-story Bauhaus modernity was the LAPD’s proud monument to itself, but it faced the street not with windows, but with a blank wall of white, cut stone ... a perfect symbol for the thinking within.

Now the building is all but doomed; the city claims Parker Center has to go, that the space it takes up can better be used for office space, even multi-unit housing. The LA Conservancy argues that this can be accomplished more cheaply without demolishing the old building.

... from the beginning, the City departments in charge of determining Parker Center's fate have acted consistently to bring about its demolition. Examples include proposing a preservation alternative designed to fail, inflating cost estimates for preservation, and proposing a master plan for the Civic Center that presumes the absence of Parker Center. -- LA Conservancy

The city council has nevertheless voted to knock it down.

I have mixed feelings myself. In the early 1980s, the Parker Center press-room was almost a second home to me, where I worked the overnight shift as a City News Service reporter. Along with a rotund, veteran reporter from the Times and a younger colleague from UPI, I was the source of all the news of Greater Los Angeles from 10 at night to 6 in the morning. And of course, I was working in what was, thanks to Dragnet, the most famous police headquarters in the world.

But I was also seeing a side of the LAPD that I had never seen on TV. A force of tough, direly overworked mostly white mostly male cops that by and large seemed to consider much of Los Angeles’ black and brown civilian population as an enemy. There were the bitter jokes about “no humans involved” shootings, and about how gunshot wounds were a natural cause of death south of the 10 Freeway. Officers sometime referred to their prisoners as “guys with unhappy childhoods.” It was the era of what you might call the “Do you hear me, asshole?” school of community policing under Chief Daryl Gates.

But it had begun under Chief William H. Parker, the building’ s namesake. Parker was widely lauded for cleaning up a severely corrupt department, but his 16 years as chief were shadowed by endemic prejudice: black men could never rise above the rank of Lieutenant; women could not rise beyond Sergeant. Integrated niteries along Central Avenue were shuttered; the LAPD presence in black and brown neighborhoods reflected his experience as an occupying US Army officer in post-war Europe, building tensions that erupted in Watts in 1965.

Parker died a year later. But his tradition survived another generation, despite the critical findings of the official 101-page McCone Commission report. In 1990, commission members told the Times their recommendations had been largely ignored. In 1992, Los Angeles’ underserved population rose up and said the same thing with the Rodney King riots. This time, the city had to listen.

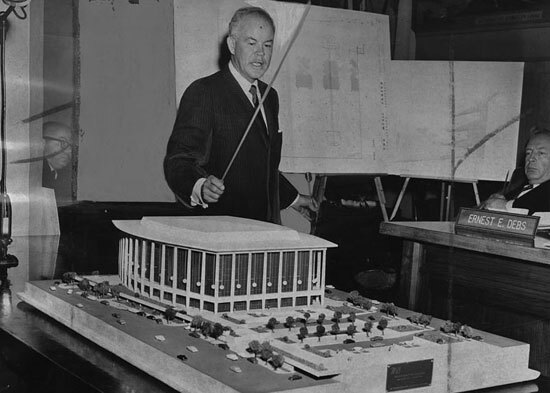

When all is said and done, Parker Center is a handsome building, one of the most understated efforts of architect Welton Becket, who also gave us the Capitol Records tower, the Music Center, the Santa Monica Civic Auditorium, and the Beverly Hilton. The problem in saving it, however, is not so much the economics, but its history. Proust wrote that there is no such thing as a beautiful prison, meaning that, whatever they look like, jails contain too much misery to be pretty. And so it is with Parker Center. It exactly represents a miserable policing policy that twice in 27 years caused the policed population to rise up and burn the city.

Maybe it is time to obliterate it, and hope that the doctrine of its namesake has been obliterated too.