This story is free to read because readers choose to support LAist. If you find value in independent local reporting, make a donation to power our newsroom today.

The Palm Springs Government Burned Down Their Neighborhood — Now They're Seeking Reparations

As evening fell on a recent chilly Sunday, Alvin Taylor looked out over a vacant lot in central Palm Springs. The sandy soil was dotted with small cement slabs, cracked from age and the elements.

“These are foundations where houses were,” said Taylor, who then pointed toward a fence in the distance. “I lived behind the gate over there.”

There’s nothing on the lot now save for the slabs, bits of debris and trash, and grass from a wetter-than-usual winter. But back in the 1950s, this was where Taylor and his four siblings grew up.

The lot is part of a square-mile section of Palm Springs known as Section 14, once home to a working-class community of about 1,000 people, mostly Black and Latino families who worked in Palm Springs’ service sector.

A thriving and safe community

In the 1950’s and ‘60s, Section 14 fell victim to a government operation to drive everyone off the land and raze the buildings to clear the way for more lucrative developments.

“My dad was a carpenter and my mom was a maid,” said Taylor, adding that his dad helped construct the building that today houses the local hospital while his mother tended to some of the celebrities who kept homes in the desert oasis.

Taylor’s dad also built their house. Like the other families here, they leased land belonging to the Agua Caliente Indian Reservation, on which much of Palm Springs sits. Section 14 refers to one of the reservation’s many numbered sections.

Racist housing policies at the time restricted where families of color could live; Section 14 was a place where they could build and own homes.

Old photos show a modest neighborhood with some nicer, larger homes, mixed in with small shacks.

What Taylor remembers is a thriving community.

“It looked like home, you know. It looked like a community where it was safe,” he said. “ I was living next to people who I know loved me and cared about me.”

But in the early 1960s, when Taylor was a child, the family was abruptly advised by the city that they’d have to leave.

Evictions and a ‘city-engineered holocaust’

The evictions had started a few years earlier. Section 14’s modest homes were eyesores to officials who wanted to promote tourism. The dislocation effort picked up steam after 1959, when new laws made tribal land available for long-term leases of 99 years — making it especially attractive to the city and developers.

Court-appointed conservators for the tribal land worked with the city to clear it. As people were evicted, their homes were torn down and burned, sometimes with their personal possessions still inside.

Taylor’s older sister, Pearl Taylor Devers, remembers what it was like.

“We would come home from school and see a house across the street would be bulldozed over, and then set afire,” she said. “Yeah, we saw it, we smelled the smoke.”

The Taylors’ home was burned down, too.

The community scattered, and for many, life was never the same. Families weren’t compensated. Taylor Devers remembers being sent away to live with an older sister, while her mom found a new place to live.

“Even to this very day, there's nothing there to even say that we were there,” she said. “The streets’ names are changed. It's just — it's gone.”

A 1968 report from the state attorney general’s office described the neighborhood’s destruction as a “city-engineered holocaust.”

In a 2019 article, leaders of the Agua Caliente tribe, some of whose members also lived in Section 14, described the tragedy there as part of their struggle for sovereignty fought with city leaders. LAist reached out to the Agua Caliente Band of Cahuilla Indians but did not receive a response.

Losses that could exceed $2 billion

Decades later, the Taylors are part of a group of former Section 14 residents — along with their descendants — who are seeking reparations.

Last year, the group filed a claim against Palm Springs, alleging the evictions were illegal and seeking damages; its attorney, Areva Martin, said their losses could exceed $2 billion.

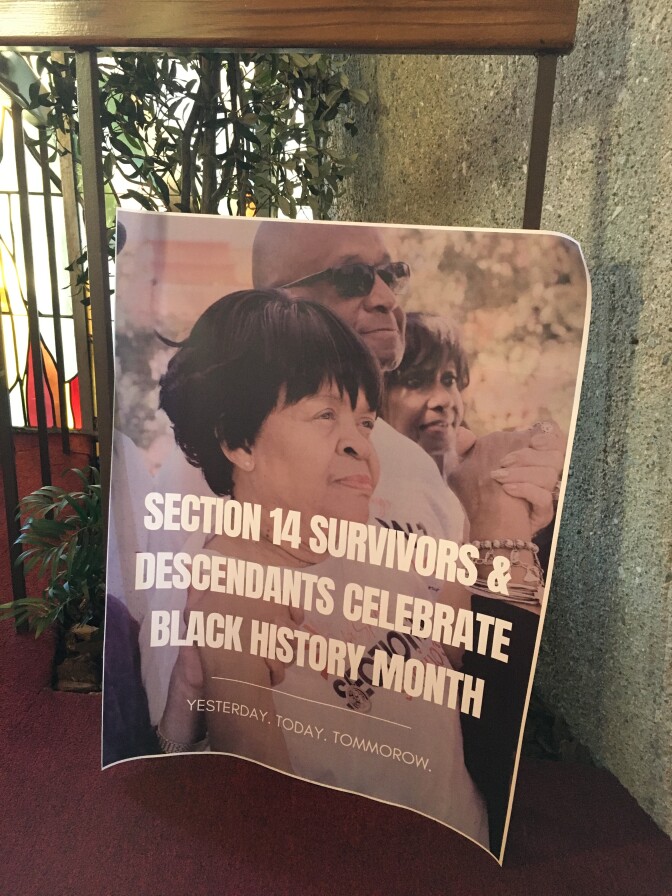

“People are awakening to a new understanding of what has been broken, and how it must be repaired,” Martin told the crowd at a February church service in Palm Springs held in honor of Section 14 survivors. “People are understanding the urgency of reparations.”

The Section 14 claim comes amid growing awareness of racist land grabs around the country that long ago robbed families of color of their properties, businesses, and home equity — and with that, generational wealth.

In the claim, Martin likens what occurred in Palm Springs to the 1921 destruction by a white mob of Tulsa, Oklahoma’s Greenwood neighborhood; a few remaining elderly survivors have been engaged in a court battle with the city over reparations for what happened to “Black Wall Street.”

Closer to home, the city of Manhattan Beach recently apologized for seizing a Black family’s beachfront resort — known as Bruce’s Beach — by eminent domain in the 1920s. Last year, L.A. County returned the land to the Bruce family, which later sold it back to the county for $20 million.

Martin said while the Section 14 families’ homes were built on tribal land, they would have gained substantial equity as the city grew, especially given Section 14’s location by downtown Palm Springs.

“They lost out on that opportunity to be the beneficiaries of the boom that happened in this city,” Martin said. “The goal is to make these families whole; the goal is to acknowledge the contributions of these families.”

The city apologizes

In 2021, Palm Springs formally apologized to Section 14 survivors. Late last year, the city began a search for a consultant to come up with a reparations program. A spokesperson said the city expects to award a contract this month.

The consultant will also be providing “additional historical research that may be necessary to develop a complete understanding of what occurred before, during and after the displacement took place,” Palm Springs spokesperson Amy Blaisdell said in an email.

The city recently released documents related to what it euphemistically called the “abatement” in Section 14, including records of houses destroyed by controlled burns.

... We were very happy there. Everybody got along. It was all races, Blacks, Mexicans, Filipinos, whites. We all got along. We were all friends, you know … we’d dance in the parking lot, and everybody came.

Many of those who remember Section 14 are now elderly. Among them is Margarita Godinez Genera. Now 84, she said her Mexican American family moved there in the late 1930s, and she grew up there.

She remembers her family helping organize the neighborhood’s popular church fiestas. Her mother would cook, and she’d help with concessions.

“I sold candy apples and all kinds of things,” Godinez Genera remembers. “And we were very happy there. Everybody got along. It was all races, Blacks, Mexicans, Filipinos, whites. We all got along. We were all friends, you know … we’d dance in the parking lot, and everybody came.”

Her younger cousin, Delia Ruiz Taylor— who later married Alvin Taylor, a former schoolmate — remembers the camaraderie.

“Everybody visited, everybody played together,” she said. “I remember all of us being out there playing baseball, playing kickball, dodgeball.”

‘I learned what racism was’

When Ruiz Taylor was entering 7th grade, her family was forced to leave. She said while many Black families moved to the windswept north of town, where they were allowed to live, her Mexican American family landed in Cathedral City.

There, she said, most of their neighbors were white. Her family was treated poorly.

“Once we moved from [Section 14], I learned what racism was, and I learned what hate and anger [are],” Ruiz Taylor said. “I learned that in the new neighborhood, when I was told to go back to Mexico — and I didn’t know where Mexico was — and I was called a wetback.”

At one point after she moved, Ruiz Taylor said she was shot in the leg with a BB gun by local boys who hurled racial slurs at her.

“That never happened in Section 14,” Ruiz Taylor said. “We all got along.”

The ‘trauma…stays there forever’

Most of Section 14 has been developed by now. There are condos and businesses, hotels, a convention center and a casino among other things, attorney Martin said.

But the area where the Taylors grew up remains bare.

Alvin Taylor said the eviction devastated his family, especially his father, who stayed on in the house as long as he could before it was destroyed.

“My dad just fell apart [and] became an alcoholic,” he said, adding, “my mom and dad broke up.”

Taylor eventually struck out on his own and built a successful career as a drummer, living in Los Angeles and playing with, among many others, Little Richard, Jimi Hendrix, Eric Burdon, Elton John, and George Harrison.

But he couldn’t shake the trauma of what happened to him as a kid.

“I got involved unfortunately with drugs and alcohol, and that was a kind of way of deadening the pain,” Taylor said.

Eventually he got sober. A little over a decade ago, he moved back to Palm Springs — and was reminded again of how much it all still hurts.

“The trauma is something that stays there forever, Taylor said. “I just remember us being treated like cattle, and herded off like sheep.”

It’s something he says he remembers each time he sees that vacant lot.