This story is free to read because readers choose to support LAist. If you find value in independent local reporting, make a donation to power our newsroom today.

Want residents, not politicians, to find answers to LA’s thorniest problems? Try a civic assembly

Here’s the scenario: L.A. has to handle a really tricky issue. Maybe it’s homelessness, rebuilding after wildfires, or community relations with police — but you are responsible for helping come up with policy solutions to address it.

You’re not a City Council member or government official of any kind. You’re just an ordinary resident, working with a group of other randomly selected residents to hammer out workable ideas for the government to adopt.

This is the idea behind a civic assembly, a process designed to bring communities closer to the public decision-making that affects their lives. Over the past decade, cities across the world — primarily in Europe but also in Brazil, Colombia, Canada and a small number of places in the United States — have increasingly experimented with civic assemblies to address questions like how to improve air quality, what to do with a city-owned piece of land, how to tackle youth homelessness, and more.

They’re not used in L.A. — yet. But some groups have tried to build momentum to make civic assemblies a reality here.

Part of that effort means letting Angelenos try the experience out for themselves.

On a recent Saturday afternoon, a group of around 30 residents gathered in a room at the Veterans Memorial Building in Culver City.

Their job was to tackle one big local question the way a real civic assembly would. The session was co-hosted by Public Democracy L.A., an advocacy group championing more inclusivity and representation in L.A.’s democratic systems, and Braver Angels, a national organization dedicated to bridging political divides.

“I’ve been dying to do this with other people,” said Joan Jaeckel, a resident from Studio City. She said the idea of civic assemblies appealed to her because it was a way to start a discussion from a point of curiosity and learning, rather than fighting from opposing political sides.

“I’m tired of yelling at the TV and writing on Facebook. But to do this with other people is exhilarating,” she said.

How a civic assembly works

A civic assembly (also called a citizens’ assembly) is sort of a cross between a city council meeting and jury duty. The idea: Gather a group of residents — chosen randomly, but also selected for demographic factors like age, race or socioeconomic status to make sure the group is representative of the broader community — and give them a big question to address.

The group then holds a series of meetings to learn about it, deliberate, and come up with a set of policy solutions. In the end, it produces a list of recommended policies that the government can turn into real legislation.

Civic assemblies are usually formed when there’s an especially complicated or divisive problem to solve. In some cities like Brussels and Paris, they’re a permanent staple of government decision-making and are formed every year.

The idea isn’t a far stretch from some of the ways local governments in Southern California already try to get residents involved. For example: K-12 schools have school site councils, made up of parents, students, staff and community members. And there are citizens’ advisory groups, which recruit residents to provide policy recommendations and feedback for city governments (like South Gate or Long Beach) or individual agencies (like L.A. Metro). However, elected officials appoint these members.

What makes civic assemblies different is their accessibility. They’re intended for as many people as possible to have a chance to participate and designed to reflect the diverse backgrounds and perspectives of the wider community — including those traditionally left out of government decision-making. Participants are paid stipends to cover the costs of transportation, child care, food and other needs so they can attend.

This inclusive selection process is one reason Culver City Councilmember Bubba Fish has been interested in the idea. The city, like many others, has struggled to get input on important local issues from residents who don’t regularly participate in city government or civic life, he said. A civic assembly was a way to hear from a wide range of residents who also had time to become fully educated about the topic at hand.

He attended the mock civic assembly to see if it could be a good fit for an upcoming task: redesigning the public input process for Culver City’s annual budget.

“I went through our budget process when I first got elected and I could not believe how few people we heard from,” Fish said. Culver City lawmakers recently agreed to set aside $250,000 to improve the budget process. They have yet to decide how to spend that money, but creating a civic assembly to help design a new budget process is one option on the table.

Alex Levy, an organizer with Public Democracy L.A., said she hoped the experience would inspire people to imagine other scenarios where a civic assembly could be useful in their communities.

“We think that these little model assemblies can provide a good avenue for smaller problems within communities that can be solved,” Levy said. “So like for a neighborhood council that’s just trying to just figure out where a streetlight goes, or bike lanes — there's all these questions that are facing these communities, and maybe an assembly could be useful for that.”

The mock civic assembly

The randomized, demographically representative selection process wasn’t part of the mock civic assembly. The group overall was older and whiter than one that would have been picked for a real assembly. But that day’s goal wasn’t to fully mimic the real thing. Instead, it was to help participants get a feel for the experience. Could people who had little to no background knowledge about the topic feel confident weighing in on policy? How would it feel to craft solutions with people of different backgrounds or opinions?

The L.A. participants received their big question to tackle for the day: “What should happen to land in areas damaged by fire to balance resiliency, safety and housing needs?”

It required a steep learning curve. Many participants said they knew little or nothing about the complicated issues involved — fire resilience, municipal finance, housing policy and more. But in a civic assembly, you don’t have to be an expert on any of the issues. The learning is built into the process.

Experts from local government, advocacy groups and other stakeholders are usually part of the civic assembly meetings, citing data, giving additional context and sharing their organizations’ stances. For this session, representatives came from Abundant Housing LA, a group that champions greater housing density; Altadena Green, which works to preserve Altadena’s tree canopy; and the office of State Sen. Ben Allen, whose district includes the Pacific Palisades. Each gave a 10-minute presentation at the start of the session to outline their organization’s perspective on post-wildfire rebuilding.

Participants split up into groups of four or five, each probing one policy idea. Among them: low-interest loans for those looking to rebuild in fire zones, forested buffer zones around residential neighborhoods, and ensuring that all new development and utilities in burn zones are gas-free.

Facilitators helped each group organize their thoughts and make sure everyone had a chance to speak. What were the benefits or negatives of each proposal in terms of logistics, finances or social effects? What questions remained?

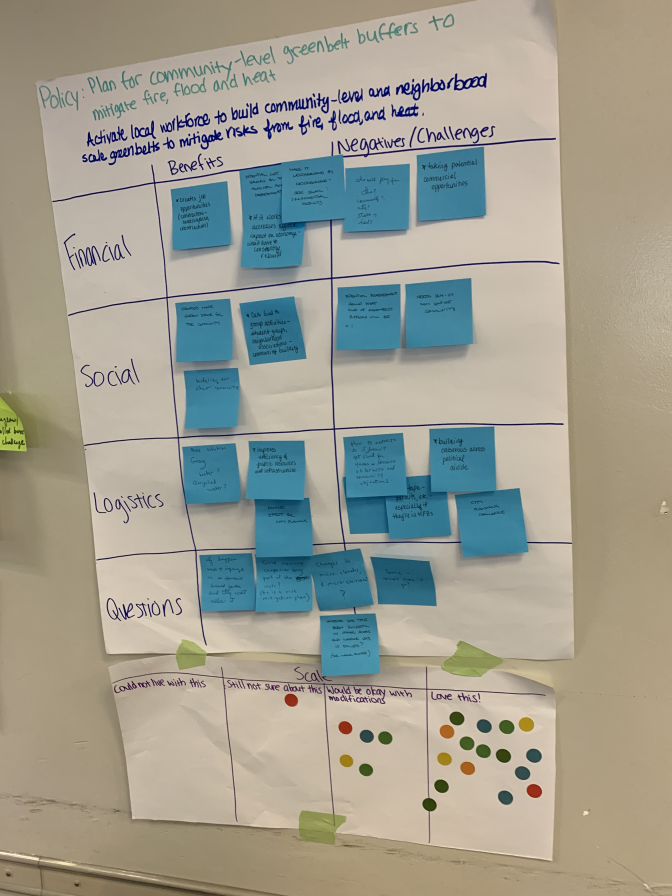

Participants scribbled on sticky notes, peppered the experts with questions and bounced thoughts off each other, at times tweaking the wording of a proposal or adding qualifiers. A proposal about giving low-interest loans to homeowners or multi-family projects in burn zones got an added caveat that those loans could be interest-free or forgivable if they provided low-income rents for the loan term. Another group changed their proposal’s language from “Plan for community-level greenbelt buffers” to “Activate the local workforce to build community-level and neighborhood scale greenbelts” instead.

There was little, if any, heated debate. Most were simply trying to better understand the full impact of the proposals before them: Are developers disproportionately benefiting from this idea? Would going gas-free for all new construction mean added strain on the power grid? Where does insurance fit into all of this? Who’s responsible for footing the bill?

At the end of the session, participants stuck colored dots on each proposal to indicate whether they loved it, would support it with some changes, still weren’t sure about it, or rejected it. In a real civic assembly, proposals with the strongest support would pass through to the official recommendation list.

How well does this work in real life?

Major legislation has come out of civic assemblies in other countries. Famously, Ireland’s citizens’ assemblies led to the repeal of a nationwide abortion ban and the legalization of same-sex marriage.

It’s hardly a slam dunk for getting new laws passed, though. For instance, when France convened a citizens’ assembly on climate in 2019, President Emmanuel Macron pledged to advance or sign their proposals “without filter.” In the end, only 10% of the group’s 149 proposals made it into the government’s climate bill unchanged, while 37% were modified or watered down. More than half were rejected outright.

But even if the actual power of civic assemblies hold to make change is a mixed bag, there’s another, more consistent effect: studies show civic assemblies are a really worthwhile experience for the people who participate in them.

For instance, an analysis of Petaluma’s 2022 civic assembly on what to do with a hotly contested fairgrounds land found that more than 90% of participants felt a growing sense of community with other members of the group and felt their input was meaningful in local decision-making. Nearly 40% reported that they were more politically active since their civic assembly experience.

In another pilot assembly to come up with solutions for child care access in Montrose, Colorado, more than 90% of participants said after the fact that their thoughts were heard, they were exposed to opinions and perspectives they hadn’t considered before, and that they supported using the same process to address community problems in the future.

Those who attended L.A.’s mock assembly seemed to share many of these feelings too.

“I was surprised at just how nuanced our discussion could get,” said Patrick Traynor, an Irvine resident. Traynor said he came because he had been fascinated by the idea of civic assemblies, but knew very little about fire safety or the finances of land ownership and renting, the issues his group was assigned to discuss. He wound up learning a lot about both topics, with help from the experts available.

A real civic assembly, he said, could help residents learn the ins and outs of complex issues in a way that they would never have time for just by filling out a ballot.

“I’m even more excited about this idea now that I’ve done this mock assembly,” he said.

Jamal Thomas from Bell Gardens said that hearing from others not only allowed him to think of solutions from a wider range of perspectives, but also made him feel like solutions were more attainable.

“Honestly, just listening to people’s experiences and what people want and need about different options and opportunities really helped me believe that there’s hope in getting some of this done,” he said.

Fish, the Culver City council member, said the experience was “incredibly eye-opening” for him.

"I was so floored by how it encourages collaboration and deep respect between people,” he said. “I went in thinking about the budget and I came out thinking, ‘How do I make this a part of our regular decision-making process as a city?'"

What would it take to bring more civic assemblies to L.A.?

Culver City’s subcommittee on governance is scheduled to hold its next meeting on Tuesday, July 8 at 3 p.m. It will hear a presentation on civic assemblies from Public Democracy L.A., and from there the subcommittee will consider whether to move forward with putting its first civic assembly together on the budget process.

If you want to give public comment on the issue, the meeting agenda has instructions on how to do so.

If you’re interested in exploring the idea of civic assemblies elsewhere — maybe in your local school, or another city government — you can get in touch with this event’s organizers, Public Democracy L.A. and Braver Angels, to see what upcoming events they may be putting together. Public Democracy L.A. also holds regular meetings where civic assembly advocates can strategize ways to bring them closer to reality.