This story is free to read because readers choose to support LAist. If you find value in independent local reporting, make a donation to power our newsroom today.

This archival content was originally written for and published on KPCC.org. Keep in mind that links and images may no longer work — and references may be outdated.

What happens to wild animals after a wildfire?

Many of Southern California’s native animals are fighting a losing battle for habitat. So what happens when the limited open space they have left is scorched by a wildfire?

That’s what the National Park Service is trying to find out by monitoring a section of the Santa Monica Mountains that burned in the 2013 Springs Fire.

Their results could help figure out what to expect from the La Tuna fire, which blazed through more than 7,000 acres of the Verdugo Mountains over the weekend.

Back in spring 2013, the Springs Fire burned through the western Santa Monica Mountains. Once the embers cooled, researchers with the National Park Service put up 30 motion-detecting cameras throughout the burn zone. Some camera sites had been completely torched, while in others, patches of vegetation remained. Researchers also installed cameras in a control area that had not been burned at all.

They wanted to find out: did fire affect certain animals more than others?

The answer was yes. In the first year after the fire, bobcats and rabbits had almost vanished from the burn zones, while coyotes, deer and skunks were thriving.

Justin Brown, the park service ecologist who lead the study, believes there are a few factors at play.

First, the disappearance of rabbits had a huge impact on predators that rely on them for food, like bobcats.

"Anytime you start wiping certain species out of the food chain it can definitely have effects on the upper levels of the food chain as well," he said.

Rabbits aren’t as mobile as bigger animals like deer or coyotes, so many either died in the fire or starved to death afterwards in the sparse, charred surroundings.

Second, some animals that disappeared from burn zones, like bobcats, simply prefer dense, woody undergrowth, which the fire destroyed.

Third, the animals that remained in the burn zones were either mobile, like deer, or able to eat a wide variety of food, like coyotes.

Brown was actually surprised by how well coyotes did in the burn zones: they showed up almost twice as often on cameras in burn areas as they did in the control areas that had not burned. Brown said he has no idea what they’re eating, but his on-going work dissecting coyote scat in Los Angeles has showed that coyotes can make a meal from just about anything.

“They’re one of the few species that’s able to adapt with us and move around the country,” he said. "There’s not really anywhere in the continental US that coyotes aren’t occurring.”

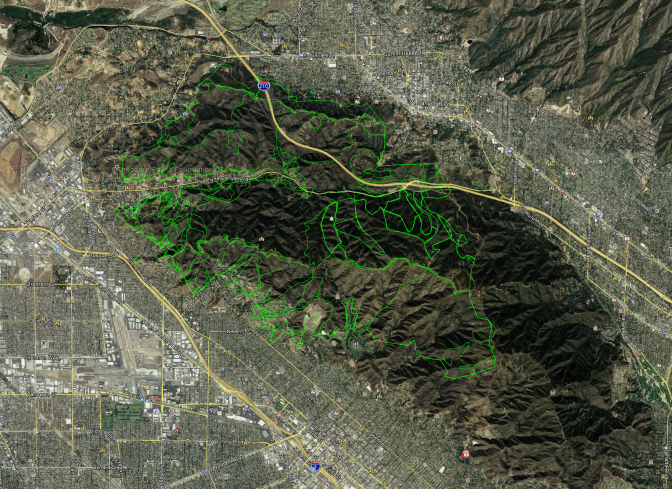

The Verdugo Mountains are a smaller, more isolated range than the Santa Monicas. They are bounded by the 210 Freeway to the north, the city of Burbank and the 134 to the south, the 2 to the east and residential development to the west.

The range has experienced 44 fires since 1937, according to Cal Fire data, and some spots have burned six times.

“One should probably ask if a ten to fifteen-year return interval is enough to get recovery of wildlife populations in burned areas,” said Tom Scott, a wildlife specialist at the UC Cooperative Extension in Riverside. “Animals are not used to dealing with an island system instead of a system where they had large areas that are contiguous.”

In particular, it could be difficult for shy animals like bobcats, or less mobile animals like lizards, to find their way back into the isolated Verdugo Mountains if an existing population died out during a fire, Brown said.

“You could very easily remove a species that’s more sensitive,” he said. “The odds of them getting back in there is almost zilch. You could easily end up slowly wipe out species by having major disasters occur.”