This story is free to read because readers choose to support LAist. If you find value in independent local reporting, make a donation to power our newsroom today.

This archival content was originally written for and published on KPCC.org. Keep in mind that links and images may no longer work — and references may be outdated.

To fight an invisible problem, researchers and health advocates give teens pollution monitors

Scott Chan worries a lot about tiny invisible particles that harm kids. He works for an organization that works to prevent childhood obesity, and he realized that there was a deep obstacle to the kids he works with exercising: invisible pollution particles in the air cause kids to get sick when they constantly breathe them in.

“People are asking us what’s better – do I exercise in bad air, or don’t exercise at all?” Chan said. Hearing this question repeatedly pushed him to look for a third way: “We really want to make sure that those are not the only two options.”

Finding a solution to an invisible problem is hard. And it can be harder to motivate people to look for solutions to a problem that no one can readily see. Chan's organization, the Asian Pacific Islander Obesity Prevention Alliance (APIOPA), wanted community members to get a visceral sense of what the air contained, so they began working in schools to do pollution air monitoring.

Despite efforts to protect children's health from the damaging effects of air pollution, thousands of children in Los Angeles still attend school dangerously close to highly-trafficked roads and freeways.

In 2003, lawmakers banned school districts from opening new K-12 schools within 500 feet, or about one city block, from a major roadway. But a KPCC analysis found nearly 90 K-12 schools still operating closer than that distance to a highly-trafficked road in Los Angeles County.

KPCC identified highways in Los Angeles County that have 100,000 or more cars zipping through them on an average day, at several different points in the county—the 2003 law uses 100,000 cars a day as the threshold for a busy roadway. KPCC then used data on K-12 schools from the California Department of Education to find sites within 500 feet of those highways.

And that's in addition to the 169 preschools, which were not included in the 2003 law, located closer than 500 feet to a major road.

It's unlikely that an established school can move, Chan said. So he began to think about how to empower students and their families to protect themselves.

APIOPA partnered with the University of Southern California's environmental health science centers’ community outreach and engagement program, which has developed a training program for community members on how to use portable air monitoring devices and evaluate the results. With APIOPA's help, the researchers brought the air monitoring devices to high schools.

“When residents understand more of the science, they are able to feel confident going to meetings and talking to city leaders about changes to clean up the air,” said Carla Truax, the outreach coordinator for the center's community programs. “Combined with the research and data about overall levels of pollution, the community monitoring is part of the picture, and aids the understanding of what is going on in the neighborhoods.”

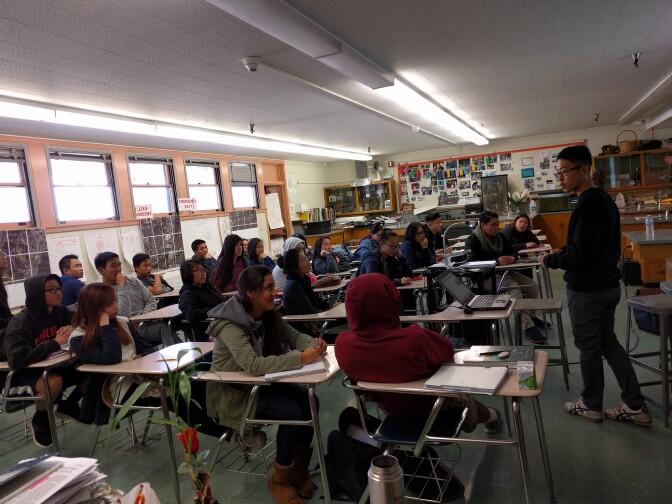

Recently, Chan partnered with high school environmental science teacher Winnie Kwan at East Los Angeles' Abraham Lincoln High School. It’s a unit Kwan developed to bring academic science out into the real world. As part of the class, the students use portable pollution monitoring devices to check the number of fine particles in the air that surrounds their school.

The school sits in the middle of three freeways – the 5, the 10 and the 110 – but not close enough to any to be in the highly polluted zone. But it is right on a major road – Broadway – which gets a lot of trucks, buses, and older cars driving up and down.

On a winter morning, as the students tested the equipment in their classroom before heading out into the streets, they were addressed by a visitor from Washington D.C., Justin Harris of the Environmental Protection Agency.

“You’re probably wondering why I’ve come all the way here from Washington to participate in today’s workshop,” Harris said to the seniors.

Harris works for an EPA program that he said aims to “advance environmental education in communities here in the U.S. and internationally.” He gave some small devices to Ms. Kwan to help with air monitoring. “These are not regulatory devices; they’re primarily intended as educational tools,” he said.

It was Harris’ first time in Lincoln Heights, and he was at Ms. Kwan’s class for a very deliberate reason. “Air pollution particularly affects vulnerable populations and so we think it is really important to engage youth because each of us can make a difference in our daily actions,” he told students.

In this case, the vulnerable peoples are these kids themselves and their families. A 2003 study by the California Department of Health found children of color are three times as likely as their white peers to live and attend school in a bad pollution zone.

Ms. Kwan’s students fanned out in small groups around the neighborhood. Their task was to watch for spikes in the fine particle count that the smart phone like machines was recording. When the count jumped, the group was instructed to stop and note down what might be causing the spike.

Kwan told the students they should also keep track of “any weather or wind patterns or big trucks that might come by.” These are all things that impact pollution counts, she told them.

Lincoln High senior Mary Chung loves the AP environmental science class. Her team noticed that idling cars with the engine on, buses picking up passengers, and trucks zooming by, all caused the particle count to jump dramatically while they were out.

Chung said she has taken lessons learned in this class right home to her family. She said it is not always welcome news, especially for a working class family trying to get by.

Chung’s sister recently bought a house in Pomona and the family was excited to have their own home. Soon after her family moved Chung learned in her class that the government has a website to check the air quality in any neighborhood. Airnow.gov ranks air quality by color: Green is good, yellow is moderate, and red is bad.

Pomona, Chung said, “was the only area that showed up red while all the surrounding neighborhoods were still yellow.”

Air quality that is bad one day may improve depending on the weather, the season, and lot of other factors. But Chung worried that her family had just moved to a high pollution zone. She told her sister, who didn’t seem too bothered.

“You know there’s a lot of people living in Pomona and if they’re ok with it then I guess that like she doesn’t really care,” Chung said. “We were thinking of moving to Alhambra, but it was too expensive.”

Alhambra did not come up red in the pollution check, she added.

After taking Ms. Kwan’s class, and realizing her own family doesn’t have the option to move to a less polluted area, Chung now thinks the solution has to be bigger, something that would help all the residents of Pomona. It’s exactly the kind of realization Justin Harris of the EPA hopes more young people can come to.

“You know, once you’re aware of how you contribute to pollution, once you’re aware of what the sources are within your community, you’re better positioned to make informed and make smart decisions,” Harris said.