This story is free to read because readers choose to support LAist. If you find value in independent local reporting, make a donation to power our newsroom today.

This archival content was originally written for and published on KPCC.org. Keep in mind that links and images may no longer work — and references may be outdated.

Jail suicide results in $1.6M settlement with LA County

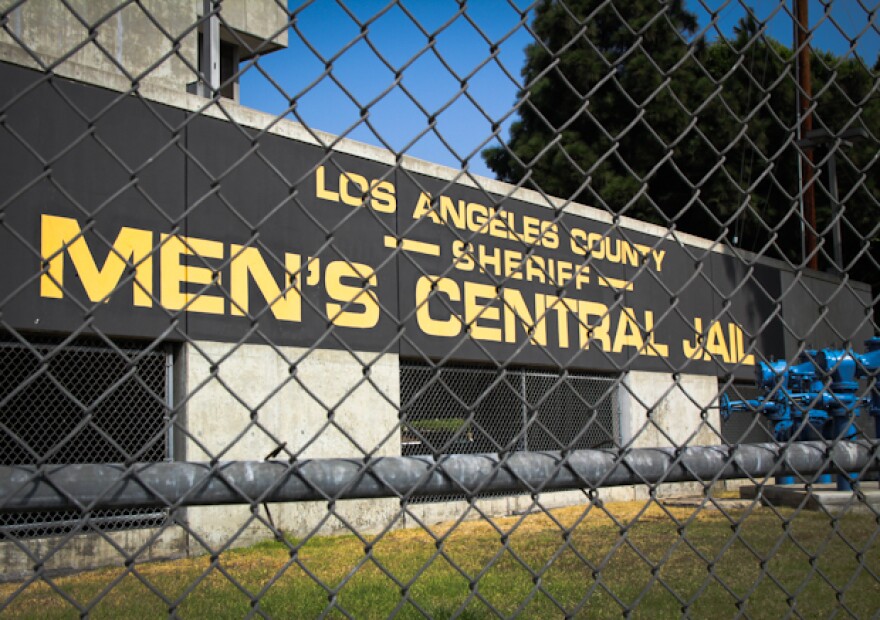

The Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors Tuesday agreed to pay $1.6 million to the family of a man who committed suicide inside Men’s Central Jail.

Austin Losorelli's death was highlighted by the U.S. Department of Justice as an example of widespread neglect of mentally ill inmates in the nation’s largest local jail system.

“This case embodies the tragic, deliberate indifference that was committed by the Department of Mental Health and the Sheriffs Department,” said attorney Ron Kaye, who represented the family in a federal civil rights lawsuit against the county.

The settlement comes on the same day supervisors voted to go ahead with a roughly $2 billion jail overhaul plan that involves replacing Men's Central with a 3,885-bed jail devoted mostly to inmates with mental health issues. (The board had previously approved the plan in a surprise vote last month--but decided to revisit the issue over concerns they may have violated open meetings laws.)

Sheriff's official want the new jail to deal with a growing population of inmates with severe mental health problems--and have acknowledged that cases like Losorelli's have stemmed from lapses in care.

Kaye called called the settlement the biggest ever in a jail suicide case in California — and a case that highlighted repeated breakdowns in L.A.'s system for dealing with the mentally ill.

Losorelli, whose father is an LAPD lieutenant, had been in jail before when he was arrested in 2013 on a probation violation. But despite information in their records that he had been suicidal, deputies placed him with the general inmate population inside a cavernous dorm room at Men’s Central Jail.

“He told inmates in the module that he heard voices and believed the television in the unit was talking to him,” according to the lawsuit. “Inmates observed him pacing the unit while grabbing his head with both hands and mumbling ‘It’s not right. I don’t feel right.’”

Deputies responded by moving him to a single man cell with limited supervision. Within hours, Losorelli hanged himself with a bed sheet from an air purification unit. He was 23-years-old.

“Its such a travesty,” Kaye said.

Losorelli’s family declined to comment on the settlement.

Opportunities missed

According to the lawsuit, Losorelli first began to show signs of mental illness in his late teens and ultimately was diagnosed with schizophrenia. He was admitted into mental hospitals on seven occasions prior to his arrest for assault on June 25, 2013.

When Losorelli repeatedly banged his head against a patrol car, sheriff’s deputies determined he was a danger to himself and placed him under an involuntary psychiatric hold. He was later released.

Losorelli was arrested again a month later for being drunk in public and resisting an officer. This time he went to jail, where he was identified as having a history of “mental disorder,” according to the lawsuit.

A psychiatric social worker noted Losorelli said he wanted to kill himself: “current plan is to hang self,” she wrote.

At an August 21 sentencing hearing, Superior Court Judge Daniel Feldstern said Losorelli should only be released into a residential treatment program. Instead, eight days later, the Sheriff’s Department released him onto the street outside Men’s Central Jail.

Losorelli ended up back at his parents’ Santa Clarita home. His father, an LAPD lieutenant, sought advice from a sheriff’s detective on what to do as his son displayed more erratic behavior.

“Detective Welch advised them to have Austin re-arrested; and that by re-arresting Austin, he would be in safe hands until a space finally opened up at the dual diagnosis facility,” the lawsuit reads.

Eight days later, he was dead.

In July, because of a rash of suicides and excessive use of force against mentally ill inmates, Los Angeles County agreed to a series of reforms and oversight by the U.S. Justice Department. Those reforms include better identification and treatment of inmates with mental illnesses, and the development of discharge plans that include treatment outside of jail.