This story is free to read because readers choose to support LAist. If you find value in independent local reporting, make a donation to power our newsroom today.

This archival content was originally written for and published on KPCC.org. Keep in mind that links and images may no longer work — and references may be outdated.

Getty: A Mughal-European smackdown and an art exchange that taught Rembrandt a thing or two

A wonderful scene played out about 400 years ago in India, a smackdown between a European painter and several Mughal artists:

The British ambassador to the Mughal court gave then-emperor Jahangir a European miniature so perfect, the ambassador claimed, that no court painter could duplicate it. Jahangir bet that they could. In the end, a Mughal painter turned out six duplicates so perfect the ambassador couldn’t tell them from the original. The ambassador ate his words and gave the painter a handsome reward.

As they plied their trade in eastern seas 400 years ago, European merchants encountered a vast civilization more advanced than their own in many ways: the newly-risen Mughal Empire of India. It covered most of what is now Pakistan, India, and Afghanistan, and is said to have been the greatest industrial power of the time. It was also a place of great culture and art, and it was in its art that the European and Asian cultures enjoyed a grand intermelding, a mutual assimilation that helped great artists from both the East and the West.

Perhaps the greatest of all of these artists was the Dutchman Rembrandt van Rijn. Besides his masterworks on canvas, he left us about two dozen pictures that he elaborated, rather than copied, from assorted Mughal originals. Most of these are now on display at the Getty Center now, along with a number of other works from both sides of the 17th century world that put the Rembrandt rarities into context.

“The critical eye and attentive curiosity Rembrandt turned towards Mughal portrait conventions still captivates viewers today. ” -- Getty curator Stephanie Schrader

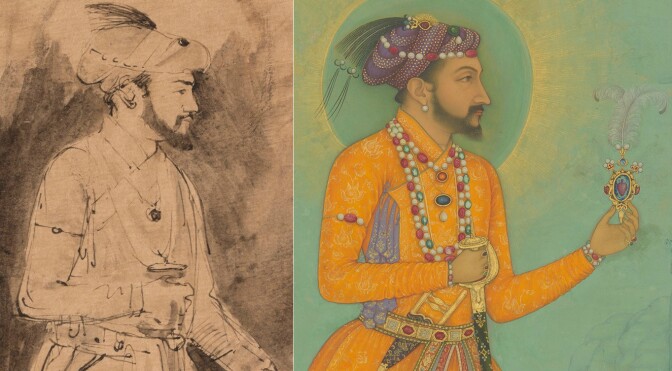

In addition to being familiar with Mughal art, Rembrandt seems also to have understood the Mughal hierarchy. Eight of his drawings on display at the Getty portray the mighty Mughal ruler Shah Jahan (“King of the World”) best known to us as the man who built the Taj Mahal. These renderings import the indications of Jahan’s towering rank, such as the halo-like gold aureole that surrounds his head, the jewels of his rank, and his “piebald” war horse.

Read Marc's review of LA Opera's “Orpheus and Eurydice,” a melding of ballet and opera

There is also a contrastingly simple, moving double portrait of the monarch and his infant son. The portraits exactly duplicate the shah’s unique features—his bearded chin, his sharp nose—and his typical garb. But the European master’s drawing techniques are totally different from those of his eastern counterparts. These oriental studies raise questions of whether they taught Rembrandt new techniques that appear in his later work.

But Rembrandt wasn't the only cultural borrower. As the Getty show shows, Mughal painters were as fascinated by European art as the Europeans were by theirs. They industriously copied and embellished European work that fell into their hands, and such work turns out to have been a major item of trade with the Far East: Schrader notes that a recently discovered European shipwreck contained hundreds of engravings and etchings bound for the bazaars of Asia, possibly to be traded for spices or indigo dye.

Most of the copies include telling differences, some subtle, some not. In a few cases, the Mughal master took a black and white European original—maybe an engraving or etching—and used it as you would a page from a coloring book, transforming it into a vivid, brilliant painting. It's a collaboration between the Orient and the Occident to create a form of art beyond the ability of either culture alone.

"Rembrandt and the Inspiration of India" is at the Getty Center through June 24.