Truth matters. Community matters. Your support makes both possible. LAist is one of the few places where news remains independent and free from political and corporate influence. Stand up for truth and for LAist. Make your year-end tax-deductible gift now.

This archival content was originally written for and published on KPCC.org. Keep in mind that links and images may no longer work — and references may be outdated.

Etienne Trouvelot, the Victorian who brought us transcendent space paintings ... and gypsy moths

Marc Haefele reviews “Radiant Beauty: E. L. Trouvelot’s Astronomical Drawings," at the Huntington through July 30, 2018.

Back in the 1970s, along with thousands of other people, I shared the losing fight for hundreds of square miles of Delaware Valley oaks, apple trees, and hornbeam. Our enemy was the gypsy moth, or more precisely, its voracious caterpillar. We wrapped tree trunks in burlap and pulled the hairy little devils off their boughs in clumps before drowning them in kerosene. How many trees did we ultimately save? Not many. We were left with plenty of firewood. And the bugs marched west into Pennsylvania. Since then, they’ve gnawed all the way through Wisconsin.

Who did we have to blame? We know exactly: an artist, astronomer, and extremely amateur entomologist named Étienne Léopold Trouvelot. In the 1850s, Trouvelot fled totalitarian France, landing in New England as a political refugee. A decade later, this maniac, while trying to breed a better silk worm, brought over a colony of gypsy moths from Europe, and allowed some to escape into the woods.

"This episode also seems to have soured Trouvelot’s passion for entomology," says one scholar. He moved on to other things—in particular, astronomy, where he almost redeemed himself by becoming perhaps the 19th century’s greatest portraitist of the heavens. His astronomical prints (known then as chromolithographs) were so astonishing that, despite his lack of specialized astronomical education, the Harvard Observatory put him on staff.

Photography was making inroads into astronomy, but Trouvelot claimed the eye was more trustworthy—which in those days may have been true. His assigned goal was, via Harvard’s new 15-inch refracting telescope, to “represent, as nearly as possible, the most interesting objects in the heavens.” More than 1,000 pictures resulted, many now lost.

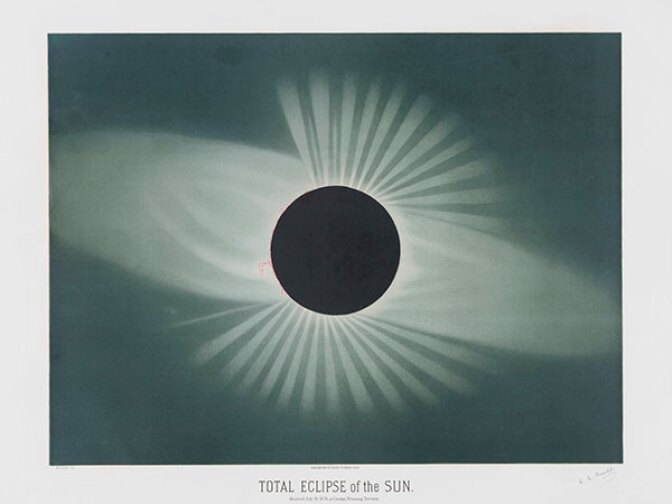

But at the far more powerful 26-inch instrument at Washington’s Naval Observatory, Trouvelot created the series of 15 chromolithographs that was his crowning achievement. Published in 1882 in New York, the complete set was priced at $125—nearly $3,000 in today’s money. They were intended for libraries and rich collectors. But due to advances in photo technology, the gorgeous renderings soon appeared obsolete. Very few of the sets now survive.

It’s one of these sets that’s on display as the “Radiant Beauty” show at the Huntington. Donated by print collector and Silicon Valley pioneer Jay T. Last (who has contributed to previous Huntington shows), the images flaunt Trouvelot’s incredible descriptive artistry and unequalled technical imagination in creating literally other-worldly planet- and star-scapes.

“He had an uncanny capacity to combine art and science in such a way as to make substantial contributions to both fields,” says Huntington curator Krystle Satrum. “But his best thing was his eye for detail.” His lithographs were compiled from sketches that took hours to complete before they were incorporated into the lithographic composites we see now.

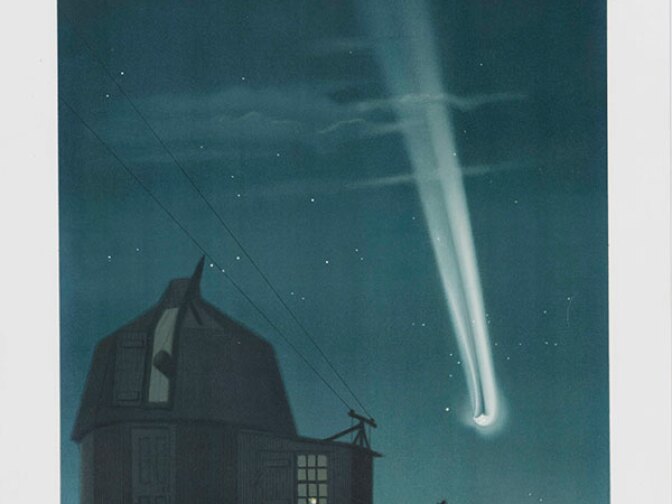

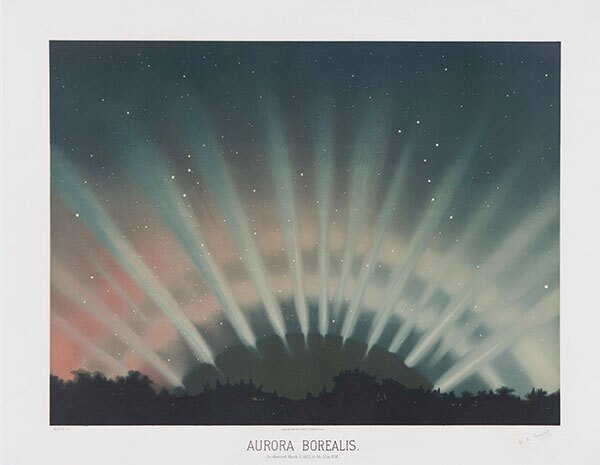

There’s “Aurora Borealis,” with its half-pink arc of astral glow pierced by straight searchlight-like beams of blue-white light. There is “The Great Comet of 1881,” zooming down toward a homely back-yard observatory.There is a lunar landscape, “Mar Humorum,” that is hard to tell from a modern photograph of the same area. There are sunspots that resemble exotic vegetation, and a picture of what looks to be a stormy Mars. It isn’t a conventional red Mars, either. The night he was making his sketches, it seems to have appeared a vivid pale green. He hypothesizes a possible ocean on Mars, but refuses to confirm it—showing that he had a more scientific mind than certain better-schooled contemporary astronomers. He only painted, as the old saying goes, what he saw. But what he saw was out of this world.

Sometimes his work reaches way out of the solar system. There is a nebula, a star cluster, a big slice of our Milky Way galaxy stretched across the sky. (This was 40 years before astronomy realized the entire universe was made up of separate galaxies.) There are renderings of Jupiter and Saturn, with all its rings, like a modern color photo, but somehow, much more. Jove shows his famous red spot. But over the spot there are two tiny dots that Satrum speculates may have been otherwise undiscovered Jovian moons.

Again, Trouvelot painted what he saw. Even when he didn’t know what he was seeing.