This story is free to read because readers choose to support LAist. If you find value in independent local reporting, make a donation to power our newsroom today.

This archival content was originally written for and published on KPCC.org. Keep in mind that links and images may no longer work — and references may be outdated.

After a week of violent shootings, what to tell the kids?

The shootings last week that left two black men dead at the hands of police officers and five Dallas police officers dead at the hands of a sniper have left families worried about how to talk to their kids about it.

For African-Americans, the issue is now a familiar one and more pressing because it involves the safety of their children.

One recent morning at a coffee shop in the Los Angeles neighborhood of Watts, patrons worried out loud: Will tension between police and the community worsen? Will there be more violence? And those who are parents wondered what more they could do to keep their kids safe.

“It makes me think to keep my kids in the house," said DeJuan Nunley, a longtime Watts resident who has two sons, the eldest of whom is middle school-aged. "It’s not even safe to go outside.”

In neighborhoods like Watts, now majority-Latino but historically African-American, fear like this over kids' safety isn't an exaggeration. There have long been tensions between police and residents, some of whom have grown up feeling like they can't trust law enforcement.

Parents warn their kids not only to stay out of trouble and avoid the powerful draw of local gangs, but also to avoid drawing the attention of police.

“I try to tell my son to keep his pants up, you know, the little styles of clothes the kids wear – it’s cool, but make sure to stay humble," said Nunley, who works as a restaurant cook.

There is a long history of officer-involved shootings involving black men; a recent investigation by KPCC found that in Los Angeles County, police fatally shoot African-Americans at three times their proportion in the population.

This reality makes for difficult conversations in African-American families, said Donald Grant, a psychologist at Pacific Oaks College in Pasadena.

"Being able to tell your children to call 911 when you are in danger, but also to behave in a very specific way to maintain your livelihood when you engage with these officers, is a challenge for many parents of color," said Grant, who is African-American and has a seven-year-old son.

While "the goal is for children to grow and understand that our police officers are here to keep us safe," Grant said, this isn't always possible in communities of color where people feel unfairly targeted.

For many African-American parents, this often leads to a painful conversation when their children — boys in particular — when they become old enough to drive.

"The conversation becomes about maintaining safety," said Grant. He would say, for example: "'When you get pulled over by a police officer, and you are so sure that you didn't do anything wrong, I need you to comply to stay alive.'"

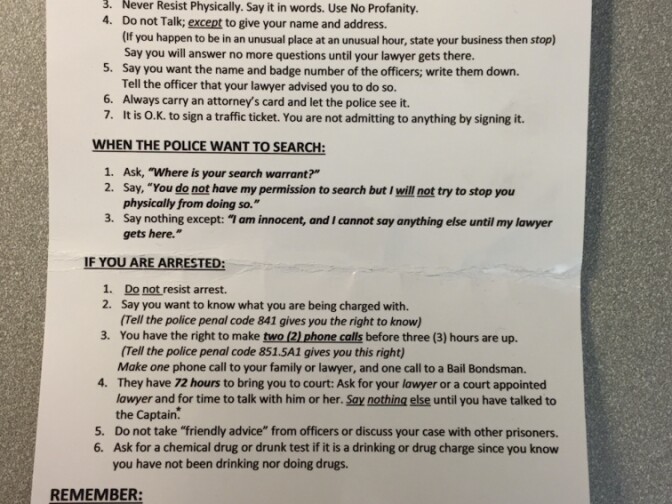

It's what some refer to as the "driving while black" conversation, one that's long prompted activist groups to disseminate tip sheets for drivers with advice like "Stay Calm! Keep your hands visible" and has even led to an advice-filled "DWB" app.

Driving aside, as with Nunley's sons, parents routinely tell their boys not to call attention to themselves when out in public and to think twice about their actions, even if it means "that you not be 100 percent authentic to yourself," Grant said. "It hurts like hell," he added.

Now, after the violence last week and the related protests in recent days, these conversations are taking different turns. It's not only about safety, Grant said, but about explaining the tragedies.

Generally speaking, he said, parents of any ethnicity trying to help their kids make sense of the news may find it helpful to explain to them that sometimes people aren't treated the same.

"People of dominant cultures tend to raise their kids in a color blind society, and they will be quick to say, 'My child does not see color,' and that is a problem," Grant said. "What we need for them to understand that different people are treated differently."

Explaining the fatal shooting last week of five police officers by sniper Micah Johnson, a former U.S. Army reservist who is African-American, last week poses a more difficult challenge. Johnson struck as demonstrators in Dallas marched in the streets to protest the recent police-involved killings of Philando Castile near St. Paul, Minnesota, and of Alton Sterling in Baton Rouge, Louisiana.

That tragedy has led some politicians to criticize groups like Black Lives Matter, an advocacy group that was formed to protest the killing of African-Americans by police and others.

Grant said the message to kids should be that feeling anger is okay, but responding with violence, as the Dallas shooter did, is not.

"We want to honor the anger and the frustration, because we'd be remiss if we didn't," Grant said, "but we want to condemn that particular method of expressing that anger."

A recent day in Watts, parents worried about that anger mounting — and being met with more violence.

“It's going to escalate, without a doubt," said Sherri Dodson, a home health care worker from Watts who has five children. "You just sit back and you wait for everything to unfold and you try to protect yourself and your family.”

Dodson, whose children range from their 20s to elementary school age, said she's given them cell phones with strict instructions. "'I need to know where you are, who you with, where you going, what time you coming back, and do I need to come and get you,'" she tells them.

But other than talk to them, she said, there's little more she can do to protect them.