This story is free to read because readers choose to support LAist. If you find value in independent local reporting, make a donation to power our newsroom today.

Happy smogiversary, LA. We don't wear gas masks anymore, but the air is still terrible

In Los Angeles, smog is a given, and most of us know its primary source is cars and trucks. But the story of how our infamous smog came to be is as thick and convoluted as the smog itself.

It was July 8, 1943, when the first real smog rolled into town, taking many people by surprise.

"People were having car accidents," said Chip Jacobs, a former investigative reporter and co-author of Smogtown: The Lung-Burning History of Pollution in Los Angeles. "Mothers were wondering why their kids' eyes were watering. Police officers were spinning loopy. It became a circus-like atmosphere in this really hot metropolitan juggernaut known as Los Angeles, and the politicians were speechless."

Because no one knew what it was.

People started wearing gas masks in public. Even Peaches, a donkey at the Griffith Park Zoo (the precursor to the L.A. Zoo) was outfitted with goggles (smoggles?) to protect his eyes from the irritating air, and yes, there is a photo.

The "daylight dim out"

Before smog was called smog, the mysterious haze that descended upon L.A. that fateful day had many names. The L.A. Times referred to it as the "daylight dim out."

So-called "heavy fumes" were to blame.

"It rolled in like this dirty, gray washcloth fog," according to Jacobs. "You could almost taste it and it smelled kind of like gasoline and chlorine. Just imagine what's otherwise a bright, humid day. All of the sudden this thing rolls in and your lungs are contracting. You can't see anything."

But where did it come from? Before smog was connected to cars, there were multiple suspects.

Some believed Japan had launched a chemical warfare attack on us. The U.S. was in its second year of heavy fighting against Japan during World War II. Just a few months before smog rolled into the burgeoning L.A. metropolis, Japan had, in fact, bombed Santa Barbara.

But it wasn't Japan.

The next suspect was a gas company butadiene plant on Aliso Street, Jacobs said. But after that plant was shut down, the smog only got worse.

So, not butadiene. Maybe it was sulfur? The scientists brought in to assess the situation just assumed it was, according to Jacobs, but they turned out to be wrong.

"Other cities have had terrible air pollution, and it was always sulfur," he said. "Sulfur is largely the product of coal-fired power plants, of which we had very few in L.A."

Finding the origin

So what was the culprit in this addled, lung-congesting mystery that had L.A.'s then-mayor Fletcher Bowron vowing to snuff it out in six months?

Smog. It's what happens when bad emissions mix with good sunshine to create air pollution. But it wasn't connected with cars until nine years after it first invaded L.A.

In 1952, Caltech professor Arie Haagen-Smit "opened up his lab window in a basement office... and brought in air, went throughout the scientific process, distilled it into acids and said, 'Aha. Now I know what's going on and you're not going to like what's going on people.'"

It was cars, in all their mass-produced, big-bodied glory. The very cars that were defining L.A. and its do-anything lifestyle were spewing noxious fumes and making a mess of the city's iconic air.

Haagen-Smit was ridiculed and vilified. But eventually he was vindicated, as officials and the general public slowly began to accept the car-smog connection, and even more slowly realized something needed to be done. Haagen-Smit's name now graces the emissions laboratory at the California Air Resources Board building in El Monte.

Thanks to advancements in car technology and California emissions regulations, it's rare we hear weather forecasts that include any reference to smog. But air quality in the Los Angeles basin has been up and down in the past few years.

In 2017, there were 145 days that exceeded the federal ozone standard in the L.A. area, according to data from the South Coast Air Quality Management District, which controls air pollution for urban portions of L.A., Riverside and San Bernardino counties and all of Orange County. That figure was up from 132 days in 2016 and 113 days in 2015.

By 2023, the number of days over the federal standard was 115.

All of that is a big improvement.

Keep in mind that in 1978, the L.A. area exceeded the federal ozone standard 234 days, or roughly two out of every three days in the year.

So we've come a long way, but there's still a lot of work to do. By 2031, the goal is virtually zero days of smog.

"In some ways, I wish we could have a 1943 every year just to remind us," Jacobs said. "When you can see it and smell it and watch your dog struggle or watch your lawn turn brown ... that was a call to action, and people's indifference does tend to follow a bell curve where it shoots up in a crisis and then dips, dips, dips.

So happy smogiversary, Los Angeles. We can breathe a lot easier than we used to, but don't let that fool you — we still have the worst air quality in America — a distinction the American Lung Association has consistently given us in nearly every report since they began more than 25 years ago.

A note on air quality this week

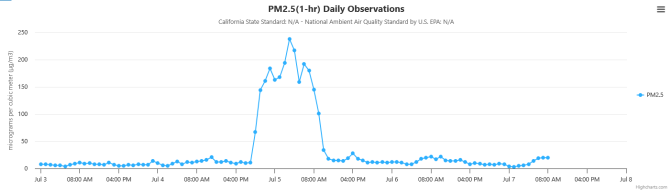

Harmful PM2.5 pollution tends to spike in Los Angeles after July Fourth fireworks. Sure enough on July 4 and 5, 2025, the South Coast Air Quality Management District's air quality index climbed into very unhealthful territory early Saturday.

The particulate matter we breathe after the oohs and ahhs is made up of strontium, magnesium and barium, among other metals and chemicals, an AQMD representative told LAist recently. Some illegal fireworks also contain lead.

“ Some of those metals are actually toxic to breathe,” added Scott Epstein, air quality assessment manager at the South Coast Air Quality Management District.

This article was originally published at 5:02 p.m. on July 9, 2018.

Matt Ballinger and Aiko Offner contributed to this report.

Updated July 8, 2019 at 6:45 AM PDT

This article was updated with the most recent air quality data from the South Coast Air Quality Management District, as well as a new link to the American Lung Association's annual State of the Air report.