Diavolo Dance Theatre is reinventing modern dance by combing architecture and wildly physical choreography; media critics have been piling on NBC for going soft on the GOP nominee, and now late night host Samantha Bee has joined the fray; Richard Nelson keeps his election-themed plays current by writing until the last minute.

Diavolo blends dance, architecture and real danger

"I’ve broken both of my ankles, heels, my left tibia, both of my hands, and my spine," says dancer Ezra Masse-Mahar. "And my teeth. They’re bones too."

Masse-Mahar in his fifth season with the ultra-physical dance troupe Diavolo, and he says the risk is a huge part of the appeal: "I love being scared, so this is a great company where I feel like that challenge will never go away."

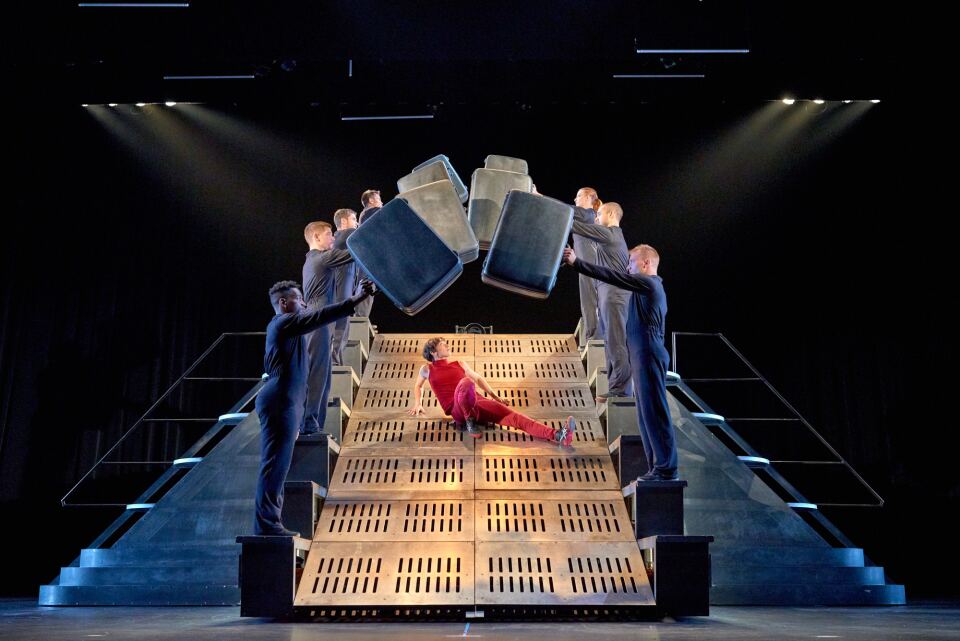

Company artistic director Jacques Heim created Diavolo in 1992 with a vision of combining dance and architecture. He incorporates huge, custom-designed props into his choreography. The prop in the company's signature piece, "Trajectoire," looks like a giant crescent moon or a ship rocking back and forth.

Working with props like the 3,000-pound "ship" in "Trajectoire" requires careful planning and constant communication between the performers.

"We have to physically call each other’s names," says Diavolo dancer Chisa Yamaguchi. "Oftentimes you can’t see what you’re looking for because we’re inside of the structure and so a lot of it is verbal cues of our names, or hearing 'set' before we fly, or even a 'no fly.' Or even communicating if a set piece has come unlocked. We make it very known to the audience that we have to talk to one another."

Heim says that this audible communication actually enhances the performance.

"The first 10 rows will be able to hear what’s happening at every moment," Heim says. "And I really believe that sometimes the reason why the audience give[s] us a standing ovation [is] because they feel what those men and women go through... And so, not only [can they] feel it, they could see the sweat splashing across the first 15 rows of the orchestra. But also, they can hear them. So there’s something very vibrant and real that is happening."

The props, or architectural structures, always come first in Heim's creative process. He works with a handful of designers. Once the prop is ready, he collaborates with his dancers.

"Like children in a playground, they discover the environment," Heim says. "They discover what they can do on it. The structure tell[s] them movement they can do, movement they cannot do. Movement more dangerous or impossible to do. So, of course, there’s a lot of collision and mishap that happens, and that’s part being a Diavolo performer. It’s a little bit like the NFL of dance. You have to be ready for major collision and impact and risk-taking."

By the time a piece is ready to be performed, there are no accidental collisions and very little chance of serious injury. But Yamaguchi says the dancers aim to make the audience believe the danger is real.

"We purposely create moments to put the audience at the edge of their seat," says Yamaguchi, "and that’s what keeps the work exciting, even though we’re very calculated in how we do it and it’s very purposeful. But the art is making it look like it’s accidental, making it look like it’s a close call or that it is actually dangerous."

Diavolo Architecture in Motion performs Sept. 23-24 at the Broad Stage in Santa Monica.