Film composer Atticus Ross took Brian Wilson's music and created sound collages for the score to "Love and Mercy"; the Academy Museum of Motion Pictures has settled differences with a neighborhood group over the new facility planned for Wilshire and Fairfax; for composer Derrick Spiva, music is all about movement.

Academy Museum of Motion Pictures to move forward with building project

The Miracle Mile neighborhood of Los Angeles is set to get yet another cultural facility. Known as Museum Row, this stretch of Wilshire Boulevard is already home to the L.A. County Museum of Art, the Architecture and Design Museum, the Craft and Folk Art Museum and several others. Now, the way seems clear for the $300 million Academy Museum of Motion Pictures.

The Renzo Piano-designed space, which will include the former May Company building at Fairfax and Wilshire, hit some roadblocks this year.

A neighborhood group known as Fix the City threatened a lawsuit if the Academy of Motion Pictures didn’t address some concerns first, including how the new museum will affect traffic in the already congested Miracle Mile area. The Academy has just reached an agreement with Fix the City and The Frame’s John Horn spoke with Bill Kramer, managing director for the Academy Museum.

Interview Highlights

Back in June, the Academy got the go-ahead from the [Los Angeles] city council to start construction on the new museum. What happened?

Fix the City, a community group we’ve been speaking with since the beginning of the planning of the project, wanted us to commit to working with them on some monitoring and mitigation efforts tied to the project. So we waited. We extended the 30-day wait period to 60 days and by the end of August, which was the end of the 60 days, we were able to come up with an agreement that worked for us and Fix the City. At that point we were able to go to the Department of Building and Safety and secure our first permit to start construction.

What is Fix the City and have they had a history of dealing with other developers in terms of what their point of view is on the neighborhood?

They have. [Fix the City] is a community and advocacy group, really concerned with the quality of life in Los Angeles overall. Great group, very sage ... So when they looked at our project it was not about what’s just happening on [our] plot of land. It’s how that project is connected to everything else that is happening in that neighborhood. And [examining] how we can work together on mitigation efforts to really make the neighborhood remain livable while we create a world-class cultural institution for the city.

It sounds as if they had a couple of concerns, [including] signage. What about in terms of parking and traffic flow?

We’re not building new parking. We have secured over 800 spaces in the neighborhood for use at our most high capacity moments, which would be the weeknights and weekends ... In terms of traffic, we will monitor traffic flow — cars coming out of our area and the LACMA area to see who is using our museum. And if it becomes overly-trafficked, we will work with them on mitigation efforts, [such as] working with the city on putting speed bumps in, better signage, directing people to our parking areas, etc.

We know from the schematics from architect Renzo Piano’s plans that the museum will include a 1,000-seat theater and event space. What else can you tell us in terms of what will be in the museum and its design?

The 1,000-seat theater, the sphere, is the most apparent part of the project. But within the May Company [building] — a beautiful existing building with great bones — there are going to be six stories of galleries that will explore the history and future of moviemaking.

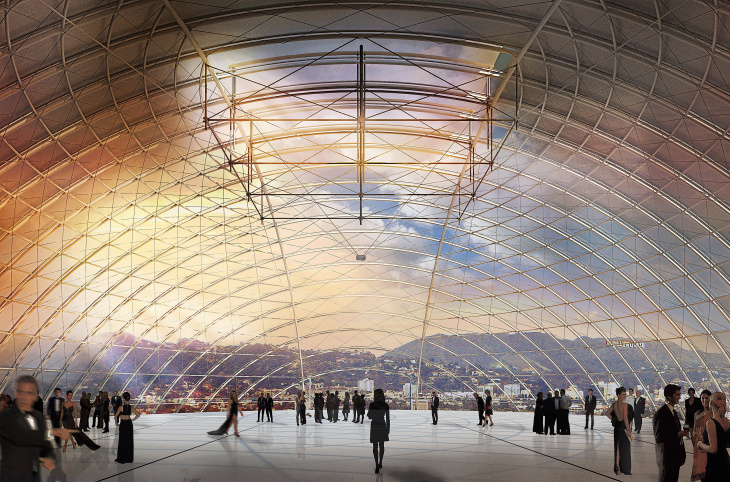

Academy Museum Rendering - ©Renzo Piano Building Workshop/©A.M.P.A.S.

Academy Museum Rendering - ©Renzo Piano Building Workshop/©A.M.P.A.S.

You still have $50 million to raise. But with the Fix the City issue resolved, are there any other issues that remain as the building of the museum progresses?

Obviously, a project of this scale has many challenges that lie ahead, and we’re prepared to tackle them. It was very important to us to work with the community. We did not want to move forward with the project without the support of our neighbors, and we were thrilled that we were able to come to an agreement with them. They’re our greatest stakeholders. It’s their neighborhood and we would not feel comfortable moving forward without an agreement like the one that we’ve just secured.

Atticus Ross breaks down the score to 'Love & Mercy'

"Love & Mercy" is based on the life of The Beach Boys' songwriter Brian Wilson, who is one of the most respected musicians living today. Composer Atticus Ross is well aware of Wilson's stature and knew that scoring the film would be a daunting task.

Ross tried to take a different approach to musician biography film scores by remixing classic tracks such as "Help Me, Rhonda," "California Girls" and more than a dozen other songs into one piece.

Ross was a rock musician before he started scoring films just a few years ago. He was in the British rock band 12 Rounds in the early 1990s, and more recently in the electronic band How to Destroy Angels with Trent Reznor. They collaborated on the Oscar-winning score for “The Social Network" and on “Gone Girl.”

The Frame's John Horn spoke with Ross on why he decided to remix Beach Boys songs, the challenges of scoring a film about Brian Wilson, and what the songwriter thought of Ross' work:

INTERVIEW HIGHLIGHTS

Were you nervous about working on a film about Brian Wilson?

Very nervous. And a film being made about Brian Wilson wasn't necessarily something that resonated with me because it's very nerve-wracking to having one's music [heard] against his catalog. Plus, I'm not a huge fan of music bios. I think there have been some good ones made, but generally speaking, not a great fan. So, eventually after much harassment, I did get around to reading the script and I thought it was a brilliant script and it wasn't at all what I expected.

I was doing some research and there was this mythology about all these recordings from those years that have never been released. So I had this idea that if we were to somehow convince Brian to give me all this recording that we might be able to do something interesting in terms of storytelling. And remarkably he was up for it. And then, even more remarkably, this hard drive arrived at my house with this phenomenal amount of material.

All of Wilson's masters?

It was all the masters, but I suppose what's more remarkable to the fan is just the amount of material. "Good Vibrations" alone — I think I've got 68 versions of it. He would leave tape rolling [in the studio] and you could hear him [in the control room]. I think that people, me included, had come to see Brian as spaced out. But when you hear him talking, instructing the musicians — [he's] incredibly focused, self-possessed, confident, direct... I mean it's incredible.

The track "Silhouette" is very representative of the film. You have your own orchestration and you're mixing it with some snippets of Brian Wilson's music?

The idea was that Brian should be ever-present. So we're taking parts of his a cappella pieces and sampling them, and then making new melodies that feel evocative of his work. And I worked with my family a lot ... my wife and my brother. But there's one scene — it's one of the darkest in the film — when he's in studio and his father ... comes in to play that dreadful "Fun Fun Fun" song. ]Wilson] goes into the control room and puts on the headphones and has this terrible experience. That was the hardest cue to do and it ended up being my wife's voice. She's singing.

When you started to work on this film, you were not enamored of Brian Wilson's or The Beach Boys' music. Did your thinking about his music and his artistic talent evolve in the making of the film?

Well, I wouldn't say that I wasn't enamored. I just wasn't an obsessive fan. Anyone who loves music can't [not] love much of what he's done. As a musical education, it really was incredible because to work out how he's put these songs together ... it's remarkable that he can achieve these incredibly sophisticated orchestrations while at the same time [creating] an incredibly catchy and beautiful song.

Brian Wilson was a collaborator on this film. What has he told you about your musical work on his life story film?

Nothing [laughs]. He's been very, very nice when I've met him, and I've heard he's very happy. I was very, very nervous about doing it. When we finished, everyone felt like they have done their best. But you could never tell how things are going to be received. It seems to be received pretty well.

"Love & Mercy" comes out on DVD on Sept. 15.

For composer Derrick Spiva, music is all about movement

Derrick Spiva is a composer who works on both land and in the water. Well, not literally — but he has composed music for synchronized swimming teams. It’s all part of his interest in the relationship between music and movement.

Spiva’s latest percussion-heavy work, “Prisms, Cycles, Leaps,” will have its premiere Sept. 19-20 with the L.A. Chamber Orchestra. When Spiva joined us at The Frame studio, we talked about his varying influences, his interest in West African percussion and composition, and how "Apollo 13" changed his life — and still didn't scare him out of wanting to be an astronaut.

Interview Highlights:

Tell us about the instrumentation in the piece, "Dance in 3, Move in 2."

This particular piece is four guitars, two violins, hand percussion and electronic percussion, as well as a small chamber string ensemble and vocals. It's kind of a hodgepodge of instrumentation.

How did that track come about? Do you hear the instrumentation, the vocal chorus? What's your first inspiration?

For that track, I was actually inspired by some North African music that I was listening to — it had a blues taste to it. And then also I'm really fascinated with rhythms — North Indian tala and stuff like that.

One of the things that I like to do is take little chunks of rhythm that you don't think would go on top of each other, and I try to find a way to actually make it seem natural so you don't even notice what's happening.

What is it about African percussion that intrigues you so much?

To me, the most unique aspect of the West African music that I studied is the fact that it really seems like an orchestra — with the percussion instruments, the dancing and the singing.

When one of those pieces that's inspired much of my recent music is executed, each person is playing a different part on a different instrument, the dancers are dancing a specific dance, their feet create rhythms and sometimes they'll also have bells on their ankles that will create rhythms, and there will be singing and clapping.

All of those things together create an orchestra of percussion and song, and there's a lot of complexity there because it's all rote learning — they don't have sheet music. [laughs]

But it's also very communal. It's not like the orchestra is playing for a dancer, or a dancer is dancing to orchestral music. It's all incorporated.

Yeah, if you're there, you've gotta get involved.

I understand that the movie "Apollo 13" played a key role in your becoming a musician. What's that story?

I wanted to be an astronaut, and I saw the film "Apollo 13," and contrary to what most people would think — you see that movie and you're like, I don't want to go into space, we'll get stuck out there — I was drawn to all the adventure, like, Oh my gosh, that just seems so awesome. But I had a lot of allergies when I was a kid, and I was like, Man, you have to be really healthy to be able to do that, you can't have all this extra stuff.

So I started thinking about why I was so drawn to being an astronaut. Was it just the movie? I really liked the soundtrack by James Horner, and I listened to it so many times that I was like, Man, the music really inspired me to want to do this. So I wanted to be involved in having an effect on people and seeing what my music can bring to the human experience.