Dissident artist Ai Wei Wei made "Human Flow," a documentary about refugees around the world; Philip K. Dick wrote the story that inspired the original “Blade Runner,” but he didn't think the movie would amount to much; folk singer Barbara Dane has a lifetime of memories.

Philip Dick wasn't crazy about his novel being adapted into 'Blade Runner'

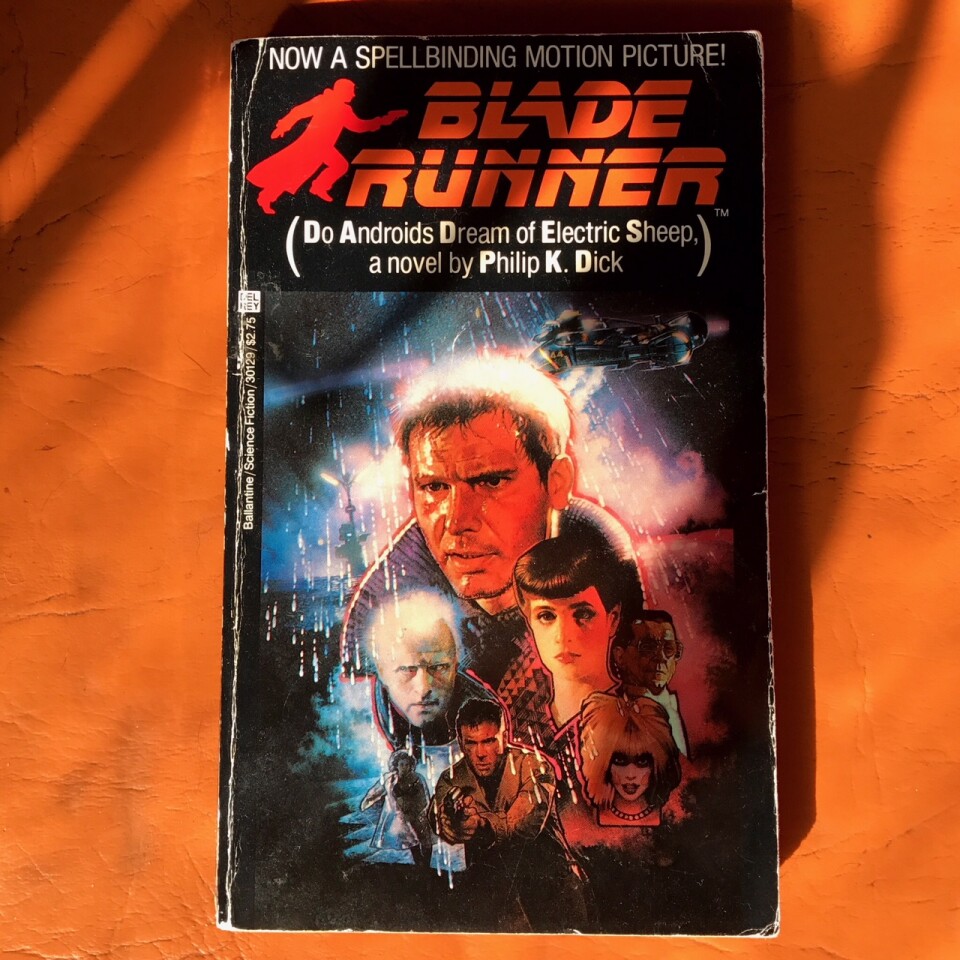

Hollywood loves turning Philip K. Dick’s stories into movies. The adaptation of his 1968 novel, "Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?," is the most iconic. That film, of course, is “Blade Runner.”

“‘Blade Runner’ started the whole Philip K. Dick revolution,” says Paul M. Sammon, a filmmaker and author of “Future Noir: The Making of Blade Runner.”

Sammon introduced himself to Dick decades ago, long before the film had shot its first scene:

"He asked me, 'Well, what [have] you read?' And I said ‘The Father-Thing.’ And he roared with laughter and he said, ‘I bet that f***** your head up.’ That was my first interchange with Philip K. Dick."

Sammon, a science fiction and film connoisseur, was thrilled when he heard rumblings in Hollywood that Dick’s “Androids” story was coming to the screen.

“But then I started to hear through the grapevine that Ridley Scott and a journeyman actor and very interesting life-liver named Hampton Fancher... was involved," Sammon says. "I actively lobbied to become involved journalistically in chronicling the film."

Sammon embedded himself on the “Blade Runner” set where he had access to all facets of the production, from start to finish. That included interviews with Fancher, an actor-turned-screenwriter-turned-producer.

“Back in ‘75, I got the idea that Philip K. Dick’s book could be turned into a movie,” Fancher says.

But there was one big problem: Fancher couldn’t find the author.

Fancher tells the story of how he finally tracked Dick down:

I went to New York to talk to his agent and he didn’t know where he was. So I gave up on the prospect. Wasn’t interested anymore. A couple months had gone by and I was walking down Rodeo Drive [in Los Angeles]. And there’s this guy across the street and he's yelling my name. And he’s pretty insistent. I run across the street and I say, Who are you? And he says, Ray Bradbury ...

Fancher had done a play of Bradbury's but didn't recognize him.

So we talked for a moment, you know, old times. And then I started to leave and I thought, Well, maybe he knows. Because nobody knew Philip K. Dick back then ... [Bradbury] brought out a pencil and wrote Philip K. Dick’s number down.”

Sammon says he became closer with Dick during the “Blade Runner” production, in part because the writer wanted to know what those Hollywood types were doing with his story.

“He used to call me his ‘Blade Runner’ spy,” Sammon says. “He would never call it ‘Blade Runner,’ he would always call it ‘Road Runner.’ That’s how little he thought of it.”

However skeptical Dick was, the “Blade Runner” filmmakers kept some of the most profound elements of his novel.

“This thing about feeling someone else’s pain and becoming human or not. That was a big one — empathy,” Fancher says.

It’s questions like these that spoke to “Blade Runner 2049” co-screenwriter Michael Green.

“The original taught everyone — myself included, at a young age — that science fiction can and should hold ideas," Green says, "that they are a vehicle for some of the best writing you can do."

So what would Philip K. Dick think of “Blade Runner”?

We’ll never know. But before the film was released in 1982, Ridley Scott invited Dick to view what he’d been working on.

Sammon recalls:

“And the lights came up and Phil was silent and he turned around and said, 'Can you [show] it again?’ And they ran it again and [then came] the famous quote: ‘How did you know what was going on in my head?’

[Dick] Called me up and said, ‘Hey man, I just saw some footage.’ And I said, ‘Yeah, I heard you were going to see it. How did it go?’ He said, ‘I can’t believe it. Where can I get a Deckard action figure?’”

Sammon says “Blade Runner” finally gave Dick’s work the spotlight it deserved.

“Then he dies,” Sammon says. “And it was such an unbelievable sad irony.”

Dick had a stroke and died in Santa Ana, California, four months before “Blade Runner” was released.

“It’s just the greatest irony that when he was on the cusp of after all these years, toiling in the vineyards of obscurity, that the light of celebrity — or at least the light of a certain financial security — was going to be shone on him,” Sammon says. “And he never really lived to enjoy it.”

For more on Philip K. Dick, check out Robert Garrova’s new podcast, PKD Files.

'Human Flow': Ai Wei Wei's doc is about more than the refugee crisis — it's about our humanity

Chinese artist Ai Weiwei has long been critical of the Chinese government and censorship there.

In 2011, he was arrested, his passport taken and he was kept on house arrest. But even while he was confined to his home, Ai Weiwei was not deterred from creating art and speaking out.

In 2015, his passport was returned, and he took his art to a new level -- a feature length documentary tracking the worldwide refugee crisis called "Human Flow," currently in select theaters.

"Human Flow" had its world premiere at the Venice Film Festival and its North American premiere at the Telluride Film Festival, where he sat down with The Frame to discuss the film.

The movie takes an on the ground look at the migrant crisis in 23 countries -- including the Middle East, Africa, Europe and Mexico. It’s an especially timely film, given that President Trump ran on a platform that was anti-immigrant and anti-refugee.

Ai Weiwei actually began working on the research for this project back in 2014, while still under house arrest. But he first sent a team to Iraq to visit refugee camps there:

The act of starting of this film after I got my passport back actually from the Chinese authority so I can start travel. I settled myself in Berlin and then I heard some refugees already come to Berlin. So I went to Lesbos, Greece to see how would they come on the shore.

Lesbos, Greece is an island off the coast of Turkey where a lot of refugees from the Middle East and North Africa end up after harrowing journeys by boat. Thousands of refugees from Syria, Afghanistan and other war torn nations have made the journey since 2015.

I met them and the moment I start to use my iPhone to shoot because it's not prepared. I was vacation with my son and girlfriend. So that moment I decide I have to make a film about this because what I have seen is unbelievable. And you see women, children jump out of a boat and they're totally foreign. They're from Syria and nobody understands their language, their religion, and even customs. I was shocked and I said to myself I want to find out who they are, why they have to give up their land and come to here.

Ai Weiwei has long been interested in political prisoners and the plight of people whose lives have been disrupted by war, natural disasters and economic issues. As an artist, he says he had no choice but to get involved and educate himself about this global issue.

The only way I feel is to get involved as individual artists. Get myself involved to learn about a situation because nobody can understand the total picture. To be in those locations, to study the history, to study very different kind of refugees. So it's education of myself to know that. Because, as artist, I have to know it. ... This film is as a result of this learning process.

This film isn’t the first time Ai Weiwei has created art based on the migrant crisis. He wrapped the Berlin Opera House in 14,000 used life jackets. A new work, "Law of the Journey" in Prague, is a large inflatable boat with human figures inside, a kind of replica of the scenes he witnessed in Greece. Through his work and life, Ai Weiwei has gained a very personal understanding about what it means to be a refugee:

Personally, when I grew up, I have the experience of being in a refugee-like situation because my father was poet, exiled. And 20 years I grew up in very remote area, our family being pictured as somewhat dangerous, different. My father is a poet, so for 20 years he's forbidden to even write a line. So you can see how wrong those kind of pictures can really affect a society as a result China has been punished its own best mind to make China like today still without freedom of speech, still doesn't stand up for standard human rights practice.

Though the film is not overtly political, it’s clear that Ai Weiwei's message in the film is that we must remember our humanity and that some people who are not welcomed on any shore not surprisingly turn to extremism:

Doesn't matter [if] you're west, you're right or left, people still avoid to really find out what made those refugees a refugee. But rather than trying to find some tactics, local tactics to shut the door and keep them out of sight and say, That's your problem -- solve it. It's not related to understanding of human condition and human rights and the human dignity. I think by doing that, it's very, very dangerous especially for the United States and Europe. Not bearing responsibility and not leading the world to give important message -- "humans as one." We have to help each other otherwise the condition can become much worse.

Watching "Human Flow" is a truly immersive experience. With cameras on the ground, Ai Weiwei reveals intimate details about the suffering -- hunger, lack of shelter, no health care -- that millions of refugees must endure. Using drones, Ai Weiwei shows the vastness of refugee camps that in many instances are larger than big cities:

Drones [are] a technology. Any new technology is questionable morally or aesthetically because it's never established that view of the view of the god or the birds. But today, the drones are so common. ... But when we use it, we very clearly understand to really try to limit... not to abuse that type of the drone. It's a very special visual effect to give very essential analyzing about human beings' relations in relation to nature, their location and the mass movement. And also to give some kind of detached feeling about when we're a little bit further, and we're a little bit from very above. You know, humans all look just like ants or some little box there. So that can give us a very special angle to make a film in this kind of scale. And also can help us to wrap up and then jump into another location because this film comes to so many locations. You always need to take a deep breath so the drones give us that chance.

Ai Weiwei hopes that by seeing the film, audiences can get a better understanding of the refugee crisis, and that they can also take action on what they have witnessed:

Understanding of humanity is above all. It's about, We're all the same. If someone being hurt, we are being hurt. So that kind of ideology has to be shared only by doing that have we had compassion for other people. We lost our home too. So that kind of ideology has to be shared only by doing so that have we have compassion for other people. We can tolerate something we'd normally think is so so foreign and so different. Someone lost their education, you feel, Oh, that could be my son. Some women have no place to deliver their children, you will say, That could be my mom or my wife. So those things we have to sounds very simple but we have to repeatedly talk about that. That makes us better as a society.

To hear John Horn's conversation with Ai Weiwei, click on the player above.

Activist and folksinger Barbara Dane taught The Chambers Brothers how to ‘do your thing’

In the early 1960s when Los Angeles had a thriving folk music scene, musicians came from all over to play at The Ash Grove.

It’s the club where folk singer Barbara Dane discovered the gospel quartet, The Chambers Brothers. In 1965 they recorded "Barbara Dane and The Chambers Brothers” — a collection of gospel and political songs. But almost as soon as the album came out, their careers went in different directions. Dane continued as a political activist while the brothers became a commercially successful rock band.

Now, Dane is reuniting with The Chambers Brothers in celebration of her 90th birthday.

Dane grew up in Detroit where she was exposed to blues music, often sneaking out at night to see artists like Dinah Washington. “I’d steal my mama’s hats," Dane recalls. "I got a long cigarette holder, gloves, high heels, fake ID and I went to hear some jazz by myself.”

Dane eventually made her name in the folk scene of the early '60s. And when she met a gospel rock group called The Chambers Brothers she had the idea to record a collaborative album.

DANE: They’ve told me about how they learned to sing as they would be in the cotton rows. They would do a little singing to relax. Their mama taught them to harmonize when they were really small. The minute I heard them I knew they’d be perfect to do these freedom songs that people were wanting so much to hear and sing in the ‘60s.

Because of the increase in racial tension and violence, The Chambers Brothers had moved from Mississippi to Los Angeles. At first, they were singing in churches. But eventually they started singing at folk clubs and cafes — in particular, the Ash Grove.

WILLIE CHAMBERS: We got booked in the Ash Grove and Barbara Dane was on the same bill. So was Lightnin’ Hopkins. And Barbara Dane says, "I think if the world could see you guys, you could maybe make it!"

So Dane recruited The Chambers Brothers for the album that she envisioned as a soundtrack to the Civil Rights movement.

Barbara Dane and Chamber Brothers - We'll Never Turn Back

GEORGE CHAMBERS: Folk music changed the attitude of a lot of people. You could say just about whatever you wanted to in the form of the song.

But The Chambers Brothers weren’t interested in staying in the folk music scene forever.

JOE CHAMBERS: Barbara Dane brought us out of L.A. to the Newport Folk Festival. We weren’t [supposed] to be gone maybe three days days. And we didn’t get back for how long? Maybe a year!

Chamber Brothers - Wade in the Water Live

Making that album with Dane helped launch The Chambers Brothers’ career as a rock 'n' roll band. But they were skeptical about making the album at the outset.

WILLIE CHAMBERS: I was a little bit hesitant because we didn’t want to get involved with anything that was political, and we still don’t to this day. You can’t do both. You can’t do music and politics. It’s like gasoline and water. It doesn’t mix.

Filmmaker Maureen Gosling is currently making a documentary about Dane’s life. For her, Dane’s mixing of politics and music is what makes her such an interesting subject.

GOSLING: She didn’t become the famous celebrity. It may have cost her in some people’s eyes, because she was also very political in that she was a member of the Communist party. She stood by her principles and she ended up having an amazing life.

Barbara Dane - I Hate the Capitalist System

Dane has gone all over the world singing at rallies. She even started her own record label, Paredon Records, to promote musical activists. And, perhaps most importantly, she’s inspired groups like The Chambers Brothers to challenge music industry norms.

JOE CHAMBERS: The bureaucracy in the rock ‘n’ roll industry called us misfits. It said, You guys are playing the wrong music. We were supposed to be doing blues … and dancing with suits on and with a backup band. We said, No, that’s not what we do. We do our own thing. Because Barbara Dane taught us the phrase, Do your thing.

DANE: I’ve always wanted the country to live up to its promises. So what I started right out doing is trying to put my songs at the service of justice and peace. And for that reason, I arrive at 90 years old and I have no regrets.

Barbara Dane performs with the Tammy Hall Trio, Osamu and Pablo Menéndez and special guests The Chambers Brothers on Oct. 21 at UCLA’s Center for the Art of Performance at Royce Hall.

To listen to the audio version of this story, click on the player above.