The producer of "The Graduate" talks about working with Nichols; why Sandra Oh went from “Grey’s Anatomy” to producing a crowd-funded animated film; was Atari’s “ET” one of the worst video games ever made?; and musician George Clinton spills all the funk in his new memoir.

Actress Sandra Oh: 'I still do not see myself represented' in kids' entertainment

After spending 10 seasons on "Grey’s Anatomy" and winning numerous awards for her role as the determined and intelligent Dr. Cristina Yang, Sandra Oh retired her white coat and left the show earlier this year.

Instead of branching off to a bigger endeavor, Oh went the other way with a crowd-funded indie project called “Window Horses.”

The project is an animated film based on the graphic novel by Canadian artist and filmmaker Ann Marie Fleming. It tells the story of Rosie Ming, a young poet who's both finding herself as an artist and as a woman of mixed race: she grew up in Canada with her Chinese grandparents, but she's also of Persian heritage.

Oh recently dropped by The Frame studios, where she talked about weeping upon finishing the "Window Horses" graphic novel, creating a movie outside of the big studios, and what it means to get this project made in light of the limited diversity in Hollywood.

Interview Highlights:

How did the story of "Window Horses" come your way, and what's the source material?

Ann Marie Fleming is the creator of "Window Horses," and also the creator of the main character, whose name is actually Stick Girl. Her animation's great, because it's very 2D and she's actually a stick girl. And since she's a Vancouver filmmaker, I've known her for a long time and we've been trying to work together. And only a couple months ago she e-mailed me and [said], "Will you do this?" And I'm like, "Okay, okay, I'll do it" ... She had already written "Window Horses" as a graphic novel. I read it in one sitting, it was almost 300 pages, and I just wept. I wept because "Window Horses" has so many things in it that I want to say, and I wanted to be a part of it — not only just adding my vocal talent. I wanted to do anything in my power to help Ann Marie get this made.

What were the specific things in "Window Horses" that prompted such an emotional response?

It's very much about young women finding their voices, which has always been something that I've really tried to do in my own work and definitely that I want to encourage young women to do. And here it happens to be in this wonderful medium of poetry. It's also about tolerance and opening your mind to different cultures; not only finding your own, but being open to ones that are not your own. Lastly, my nieces are of mixed race, and Rosie is Chinese and Persian, and it is really important to me to be able to present those stories and those images and have my nieces feel like they are reflected in this society.

A character who's living with Chinese grandparents and who's of Persian ancestry isn't what we typically see represented in most entertainment.

Oh, absolutely not — and the more specific, the more universal. Again, I think it also has to do with the animation: it's very simple and unique and beautiful. And with that it gives people a wider space to be able to see themselves in a girl who's a circle with two little eyes and two little pigtails. So that's a real opening. She is specifically Canadian, she is specifically Chinese, and she's discovering her Persian heritage.

Did your decision to use Indiegogo occur because you were rejected by the more traditional channels of production? Or did you just want to get this story out there in your own way?

Honestly, Ann Marie and I never once thought about trying to make this film in a traditional way, because the scope is a very small, independent project. And not only that, our outreach was not necessarily to the big studio system. [laughs] I'm not saying that that cannot come along in the "Window Horses" development, but we really wanted to keep this a small, grassroots effort. Now, even though it's a small effort it's also a big effort to try to raise awareness and raise the money through the Indiegogo campaign. Having been in the Hollywood system, I'm definitely interested in what it means to be outside of it and what it means to embrace being outside of it.

How do you view "Window Horses" now that you've left "Grey's Anatomy"?

This is like a full-time job. [laughs] So I would say that I would not have been able to give the time and the effort that I'm giving "Window Horses" now if I were still on "Grey's Anatomy." And of course this is my work after "Grey's," and I've been taking my time trying to find the right projects that I really love. And this is definitely one of them.

Is storytelling in Hollywood more open-minded about different ethnicities when it comes to casting or depicting characters? Or is there still a long way to go?

Having been on "Grey's Anatomy," which was such a life changing experience for me ... We have to remember: 10 years ago, a cast that was half not-white was not really a part of mainstream. And somehow it was the right time and right combination where people embraced it. That's one of the proudest things I feel about having been on "Grey's Anatomy" — being a part of that cast and ... people seeing faces that they don't necessarily usually see.

Having said that, a part of my desire of doing this animated film, which is not mainstream television, is because I want to go further with ... what I feel the messages are that I'm interested in, which is mixed-raced girls and that they're the heroines. I want my nieces to see themselves and then be heroines. So those girls who are actually Chinese and Persian can see themselves. It will be transformational because I know that, myself — having grown up in Canada and here in the United States — I did not see that enough in my own life. And one thing that I can say about animation: I've been seeing a lot of kids' movies and in that realm I still do not see myself represented in children's entertainment, children's films and in animation. Not at all.

Find out more about "Window Horses" on its Indiegogo page.

Why Mike Nichols got the gig to direct 'The Graduate'

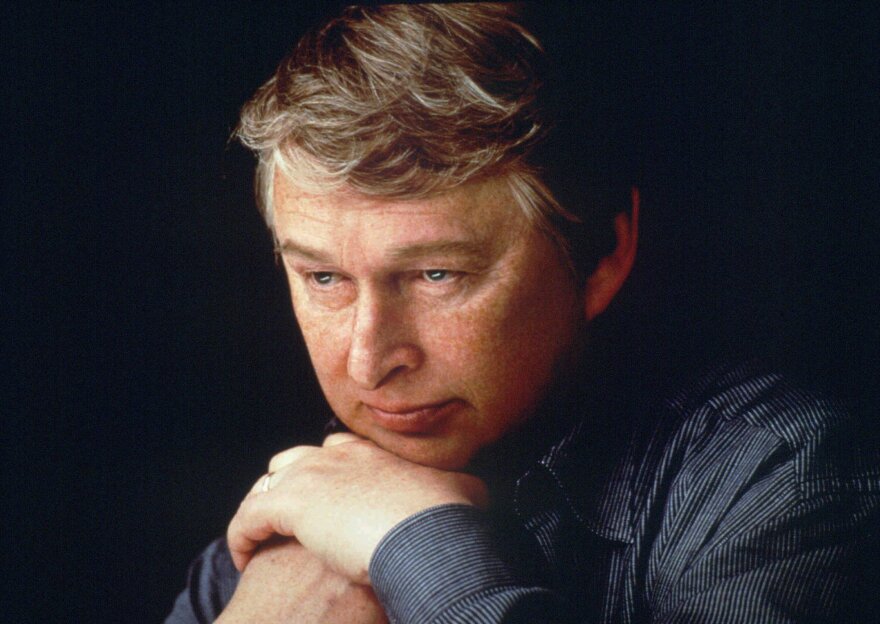

With the news of Mike Nichols' death, we spoke with producer Lawrence Turman about their collaboration on "The Graduate."

Turman would go on to produce many films — including "American History X" — and to chair the Peter Stark Producing program at USC.

Nichols would go on to direct landmark feature films, TV movies and Broadway plays. But back when Turman first reached out to Nichols, they were still at the start of their careers. Nichols hadn't even yet directed "Who's Afraid of Virginia Wolff" — his feature film debut.

Why Turman wanted Mike Nichols to direct "The Graduate"

If you've read Malcolm Gladwell's book, "Blink," it was that kind of decision — meaning when I offered "The Graduate" to Mike Nichols, he had never done a movie. And had only done a single Broadway play, "Barefoot in the Park," which I saw as just oozing smart, sensitive, funny direction. At the same time, I'd been a fan of Nichols' and [Elaine] May's stand-up comedy show. And I felt it was just an intuitive marriage — funny but mordant with an edge because that's the novel, "The Graduate," which I had optioned with my own money. It just seemed a hand-in-glove fit: that book with Mike Nichols.

On the attributes Nichols brought to the film

He's smart. He's funny. He's pinpointed. He has great people skills. Whether he's talking to a reporter from Afghanistan or to Richard Burton and Elizabeth Taylor or a seeming neophyte Dustin Hoffman, he seems to have intuitively the key to whatever it is that unlocks that person's security and confidence.

How Turman and Nichols worked together on "The Graduate"

Mike had an unusual, what I think, quite wonderful quality. I would suggest something to Mike and he would turn to me and say, "Turman, that's the absolutely dumbest idea I ever heard in my life!" That's during the day.

That night, at home, I'd get a phone call from him. He wouldn't even say "Hello." He would say, "You know I've been thinking...." and we would launch into a very productive discussion [and] sometimes it would end with him liking my suggestion. Other times no. We were both smart and lucky in that movie.

Tearin' the roof off with George Clinton

Whenever George Clinton hears the adage, If you remember the ‘60s, you weren’t there,' he's got an answer: “I was there for real!”

Dr. Funkenstein, now 73, recently visited KPCC to discuss some of his iconic music, as well as his entertaining new memoir, "Brothas Be, Yo Like George, Ain’t That Funkin’ Kinda Hard on You?"

In the book, he details his rise from scuffling doo-wop singer in the 1950s to tripped-out acid rocker during the '60s, and then his funky you-had-to-be-there meteoric rise throughout the '70s as symbolized by his creation of the Mothership, and his music empire’s massive stamp on the evolution of hip hop in the '80s and beyond. It’s a compelling, often humorous tale, rich with details awash in astronomical highs and drugged-out lows.

INTERVIEW HIGHLIGHTS

On the early years

During 1959, ’60, I’m trying to be a doo-wop singer. The Coasters had a big influence on me. I worked right next to Leiber and Stoller and I thought that was the funniest stuff in the world. And we [the Parliaments] could do that for real. And “Poor Willie” [our first single] was our shot at becoming…[sings] Poor Willie, look at Willie got a bro-o-ken heart.

The next phase

I had no idea what I was doing. I just was trying to come to a sound that I was hearing on stuff that I liked. We came out there for “Testify," which was a hit right at the same time as “Sgt Pepper’s”… We never had a chance to do what we had planned on, Parliament-wise. We had a couple of suits, but soon after we got to Detroit we pretty much started realizing we had to at least just have nothing but a flowery T-shirt and some beads. We realized immediately the suits wasn’t necessary.

Doin' their thang

I was trying to shock. "Free Your Mind and Your Ass Will Follow" — I didn’t know what I was saying. We knew we was on our way into a psychedelic thang. And that’s where we went with it. Our mission was to stay underground and not try to be competing with Top 40, 'cause I wanted to do an album that would be like jazz or rock 'n' roll… Where people would have the albums forever.

But I could agree and go and try and get a hit record. We did. “Chocolate City” was a hit. “Up for the Downstroke” first, then “Chocolate City.” But when “Mothership” happened and it was a hit, I knew [that] you don’t get paid on the back end anyway from record companies. But they will pay bills. Get me a spaceship! Got me a spaceship. I promoted Parliament, Funkadelic, who was on another label — I offered them Bootsy [Collins]… So we promoted all three groups with that spaceship for 10 years.

'Atari: Game Over': The true story behind the 'ET' video game debacle

In 1983 the video game industry crashed, and it crashed hard.

Over the course of two years, revenue for the industry fell 97 percent, and the company that was hit hardest by the crash was Atari — at that point the fastest-growing U.S. company in history.

The catastrophic downfall of Atari and the gaming industry was generally due to a combination of market saturation and overproduction of game cartridges. But that didn't stop people from finding a different scapegoat: Atari developer Howard Scott Warshaw and his final game, 1982's "E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial."

The urban legend surrounding the game was that Atari made so many cartridges and that the game was so bad that the company buried millions of cartridges in a landfill in Alamogordo, New Mexico.

Director/writer Zak Penn wanted to literally get to the bottom of the Atari video game burial, and his new documentary, "Atari: Game Over," explores both the history of the company and the process of excavating a dump in New Mexico.

When Penn visited The Frame, we talked to him about balancing the multiple stories in "Atari: Game Over," the pitfalls of video games that follow successful movies, and what it feels like to help rewrite history.

Interview Highlights:

So, what exactly is the urban legend of the Atari video game burial, and what actually caused it?

The "urban legend" is that Atari dumped millions of "E.T." game cartridges in the desert because the game was so bad that they had to bury it. The movie is very much about how that story came to be, that's one of the subplots. Atari did bury quite a bit of stuff — 750,000 cartridges, to be precise — but the story is filled with inaccuracies and everything's kind of upside-down about it, including "E.T." being the worst game ever, which it is absolutely not.

They had less than five weeks [to] get it out for Christmas. Because back then, and I still think it's true, that if it doesn't come out for Christmas, then it's not worth doing. And the movie was obviously still in theaters, too. So it was this impossible task that nobody else at Atari wanted to take, and Howard Scott Warshaw had designed "Raiders of the Lost Ark" for Spielberg, who really loved him, and he said, "I'll do it, what the hell." And he just worked on it 24 hours a day.

How did you balance the story of the excavation with Howard's story? Did you always know that you really wanted to involve him, or did his story develop as you were filming?

Even when I came on it was obvious that Howard would be a big part of the story, and frankly —and I think Howard would admit this — in the first interview I did with him it was very hard to get him to admit that he really was upset about any of this. He just has developed this really good coping mechanism of, I don't mind.

And the way I got through to him was by saying, "Listen, I wrote a movie. The first movie I ever wrote, 'Last Action Hero,' I was fired the day they bought it. And then the movie comes out a year later that my friends and family hated. And everyone hated and it was called an enormous bomb. And I can tell you that, 20 years later, when people started re-evaluating the movie, and particularly when they say, 'It's a great concept,' or, 'I read your original draft,' it's crazy. Yeah, I've gotten over it, but of course I feel better." And I think once I started to share my experience, he opened up and was like, "Yeah, it's annoying. No one else in the world could build a game in five weeks, and I did it."

So what were the complaints with the game? Why was it considered bad?

First of all, it was never bug-tested because he did it in five weeks, so there are bugs in the game, one of them being that you keep falling into pits. Everyone said, Why are there pits? There's no pits in the movie. But actually E.T. does end up in a drainage pit of sorts. But because of these glitches in the game, you used to fall in the hole if your head even passed the hole.

What people don't realize is, no one had made a fully-3D game like this before, so there's a reason Howard didn't consider that. Nobody had done it before, so he wasn't thinking about the fact that when your head crosses the plane of a hole, of course you're not going to fall in.

But there were other things, too. The game was too hard, the timer went too fast, and even in the instructions it kind of told you when to stop playing because there was no natural end — you just played it over and over. So there were a lot of legitimate problems that never got bug-tested.

Was there a point during the actual excavation where you thought, What the hell am I doing here?

I think that point began the first day I got out of a car and realized I was shooting a movie in a landfill, and that continued up through the horrible sandstorm, which practically blinded people. It looks bad in the movie, but it was worse. [laughs] It really was insane. We had to stop shooting because the excavator we were using was about to tip over from the winds, and that's a heavy piece of machinery. So we all had to go take cover, go off in cars and stuff...it was apocalyptic out there.

There were moments all the way through, but particularly the day of [the dig], where I thought, These people have come out here for nothing. It's my fault. What the hell am I doing? Can I leave? I find that often goes through my head; the couple times I've directed I've always had these moments of, Could I get fired, or leave? And you just have to fight through it.

It feels like "E.T." almost set the precedent for lackluster video games coming on the heels of successful movies. Are they always just shotgun marriages?

Having worked on some adaptations of movie games, I think they often are a shotgun marriage, and I think it has more to do with the production pipeline and the way things have to be linked up. One of the things about video games that's equally true of movies: if either of them are put on a rushed track, they will suffer. Once in a while, a great movie comes out of being rushed, and once in a while a great game comes out of it, but in general the best games are the ones that are developed until they're right, Pixar-style. Like, We work on it until it's great. But I think, for the most part, it's pretty hard to adapt a movie to a video game well. It takes a lot of time.

Why did the myth of the Atari video game burial last so long in pop culture? And how does it feel to help rewrite history?

One of the most interesting things is how this story came about. Where does — call it a legend or call it a meme — this idea that "E.T." is the worst game ever come from? That didn't start until way, way after the game was ever released; 20 years later is when people started saying it was the worst game ever, which is kind of interesting. Howard's explanation was that an industry has to be around for 20 years before people can start making lists about it.

I also think it has to do with the rise of the Internet. What's interesting about this story is that, unlike the Loch Ness Monster — which is something else I spent some time studying and which started with a sighting that was probably not true and ... turned into the legend it is today — this myth kind of went backwards. "E.T." came out and it was a disaster and it wasn't a great game, and the industry did fall apart. And it was buried. And then many years later people started saying, Wait a second, this game was buried because it was so bad. That must be the story here. The story kind of coalesced in the most natural way that it could, and that's what became the legend now. And as a screenwriter that's partly what fascinated me about the whole thing.

"Atari: Game Over" premieres tonight on Xbox.