Don Randi recalls his days as a pianist in the legendary studio band The Wrecking Crew in his memoir, "You've Heard These Hands"; the documentary "Song of Lahore" tells the unlikely story of how a group of Pakistani musicians found worldwide acclaim; YouTube enters the streaming biz with a new app.

In 'Song of Lahore,' Pakistani musicians fight social stigma to play the music they love

The quest for YouTube notoriety isn't just for teenagers. In 2011, Sachal Studios — a coalition of traditionally-trained musicians in Pakistan — posted a video of their rendition of "Take Five" by the American jazz master Dave Brubeck. The musicians were in search of a wider audience because their own country had become alternatively hostile or indifferent to their work.

The video was a hit. It earned the attention of Dave Brubeck himself — and then of jazz trumpeter Wynton Marsalis, who is also the artistic director of Jazz at Lincoln Center. Marsalis invited the group to travel to New York City and perform a concert in collaboration with his orchestra.

Sharmeen Obaid-Chinoy — who has won two Academy Awards for her short film — and Andy Schocken documented the musicians' journey in "Song of Lahore," which is now playing in theaters.

Obaid-Chinoy and Schocken spoke with The Frame's John Horn about the film and about the musicians' wider significance to Pakistani culture. Obaid-Chinoy, who grew up in Pakistan, reminisced on the social climate that made an organization like Sachal Studios a rarity.

INTERVIEW HIGHLIGHTS

Obaid-Chinoy: There are no formal music institutions in Pakistan. The way music is carried down is from father to son, uncle to nephew, in people’s homes. We had a very vibrant film industry. We had concerts, clubs, and cabarets. On Sundays on the streets musicians played. And then at the very end of the 1970’s, we had a general that took over the country, General [Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq], who decided that the Islamization of Pakistan was very important. Suddenly, the music industry started collapsing.

Because it was considered sinful.

Obaid-Chinoy: Yes. [Zia] closed off all the avenues that existed for musicians, and dried them, so they had no ways of earning money. The film industry collapsed. Clubs shut down, alcohol was banned. Cabarets were deemed illegal. And suddenly this industry that had existed no longer did.

No one ever said, It is illegal to play music. What they said was, If we take away all the avenues that are available to them to play music, no one will be able to listen. So they did it far more cleverly than banning music.

And also musicians are perceived to be in a lower social caste, so there’s a stigma against being a musician.

Obaid-Chinoy: Pop musicians are wealthy. They have this level of protection about them. But these are poor musicians that play instrumental music, and they live in sequestered neighborhoods where people do frown upon music. Where if you hear music, you’ll hear a neighbor — he might just come up to your door and say, This is un-Islamic. I don’t want to hear it.

So something happens in 2004 where a bunch of these musicians found Sachal Studios.

Obaid-Chinoy: Izzat Majeed is the founder of Sachal Studios. He is a philanthropist and a businessman. A Pakistani who lived outside of the country for many years, and came back in 2004. He wanted to preserve some of these instruments and these great masters who were dying. There are so many instruments in Pakistan where people can no longer play them, because the great masters have passed away and not passed it on.

So he came back to try to revive and find an avenue for these musicians to record their music. That’s when he set up a studio in the city of Lahore.

How does jazz fit into the narrative of what the musicians are trying to create?

Andy Schoken: At Sachal Studios they were putting out folk albums, traditional music. [But] they didn’t have a local audience . . . They basically decided that they were going to look West, and find an audience located outside of Pakistan.

In the 1950s the U.S. State Department had a program called Jazz Ambassadors. They sent some of the great jazz masters around the world — Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington, and Dave Brubeck. And Dave Brubeck came through Lahore in 1958. The founder of the studio had been at the concert and he’d always been struck by that. So he thought, why don’t we try to integrate some of these Western harmonies into our music? As a way of keeping our instruments vital, and a way of keeping in touch with our classical roots, but in a contemporary format. So that’s when they first recorded their rendition of “Take Five.”

And what happens when they record a video of this song?

Obaid-Chinoy: They put it on their website, on YouTube — the single goes up in the digital charts. It becomes number one. Dave Brubeck heard this rendition and wrote to them and said it was the most interesting rendition of “Take Five” he had ever heard. And then Quincy Jones wrote to them. Then Wynton Marsalis and Jazz at Lincoln Center heard about these musicians, and then invited Izzat to come to New York and figure out how they were going to have a concert and a collaboration.

So they these musicians come to New York. What happens when they go back to Lahore?

Obaid-Chinoy: Firstly, they made headlines. All the newspapers carried articles about them. Suddenly, all the television channels were interested in them. But more than that, I think Sachal always wanted to cultivate new audiences, and they wanted avenues to play their music. And once they went back to Pakistan, they were able to play a concert.

To them it kind of a bigger deal to play Lahore than to play New York because they’re playing for their own people. I remember one musician turning to the other and saying, “I hope somebody comes to the concert today.” And then outside when we walked in, until my eye could see, thousands of people [were] lined up. When the doors opened, and when the musicians walked out, the kind of response — the thunder of applause. So welcoming.

So what’s happening in the nation itself? Is it more accepting of music now?

Obaid-Chinoy: Well, with the Sachal musicians, and the kind of instrumental music they play, I think what they were able to do was make it cool.

But “cool” is still at odds with fundamentalist Islam.

Obaid-Chinoy: So, any music is at odds with fundamentalist Islam. But there is a huge push in Pakistan against fundamentalist Islam, especially in the last 18 months. The number of terrorist attacks have gone down exponentially. A number of avenues have opened up for artists and musicians that didn’t exist before. And I think that if we are able to hold the terrorists at bay, and that fundamentalist ideology, you will see some of this flourish again.

"Song of Lahore" is currently playing in select theaters. This segment was first published in November 2015.

In 'You’ve Heard These Hands,' pianist Don Randi chronicles his career with The Wrecking Crew

In 1962, a young pianist named Don Randi was asked to play on a recording session at a Hollywood studio. The song was “He’s a Rebel” by The Crystals, with Darlene Love singing lead, and the producer was Phil Spector.

Randi became a regular on Spector sessions, along with many other musicians who would become known as The Wrecking Crew. That group became the go-to studio band in Los Angeles in the 1960s and '70s, playing on hundreds of hit songs with everyone from The Beach Boys to Frank Sinatra to the Jackson 5 and The Monkees.

Don Randi has written a memoir about his time with The Wrecking Crew. It’s called “You’ve Heard These Hands,” and he recently came into The Frame’s studio to talk with Oscar Garza about those special days.

Interview Highlights

On moving from jazz to playing pop with The Wrecking Crew:

[Studio work is] how I made my living, and it became my living for many years. The jazz was the ultimate for me, and I got to do many albums with myself as the Don Randi Trio and then as Don Randi and Quest. I have 21 albums over the years. A number of them are still in my garage (laughs)... I enjoyed [The Wrecking Crew] ... the camaraderie ... all the guys that were there. They were a terrific bunch of musicians and they took me right in from the first day on.

What we did for all those different producers, we were basically capable of playing any genre of music. And there weren’t many guys that could do that. And all those guys that were in The Wrecking Crew and before that in [Phil Spector's] Wall of Sound, they were all jazz players. I’d be sitting next to one of the great guitar players like Tommy Tedesco, Barney Kessel, Howard Roberts ... It was always great musicians that were doing that because jazz is what they loved, but they also had to earn a living. And there was so much rock 'n’ roll being recorded in Los Angeles that we were the ones they called on.

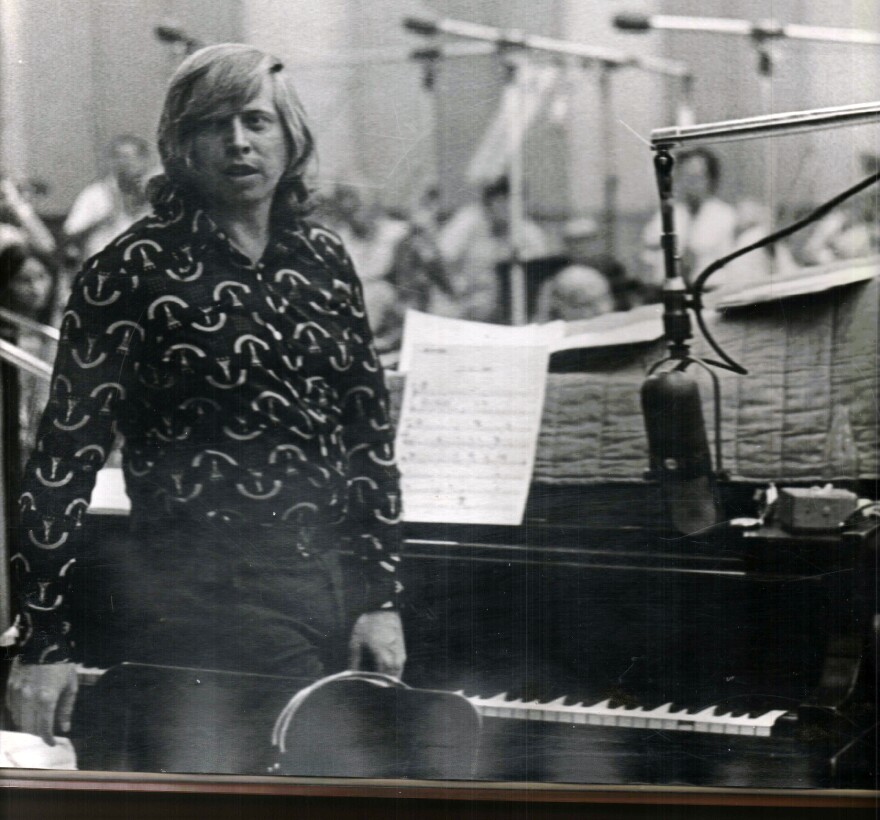

Don Randi (at piano) and Quest playing at The Baked Potato in Studio City California (Mid 1970s). Photo from Don Randi collection.

Don Randi (at piano) and Quest playing at The Baked Potato in Studio City California (Mid 1970s). Photo from Don Randi collection.

What was it like working with Brian Wilson in the studio?

It was amazing because ... his talent was so brilliant. And many of the times you’d be working with him, he knew where he wanted to go ... If you played something he didn’t like, he’d let you know right away. Or if you played something he really liked, [he'd say], Stay with that, let’s do that. And he had the facility to remember everything. And when we did, for instance, “Good Vibrations,” we ended someplace in another world because it was that incredible. And it took us three months. We were in and out [of the studio] over three months with that song.

On recording “Help Me, Rhonda” with Brian Wilson after an earlier version appeared on the album, "The Beach Boys Today!"'

I sat there right after we went through it and I said, “My God, this is a stone cold hit.” I didn’t know it had been [previously] recorded until I got together with Leon Russell one day. He says, “You know, I think I played piano on the original one.” I didn’t even know there was another [version].

On playing harpsichord on the Stone Poneys’ “Different Drum”

[The sheet music] said, “Baroque style” ... So I just played on a rock 'n’ roll record what Bach would have had to play.

On what it was like working with artists like James Brown, Frank Zappa and Lou Rawls.

Someone asked me, “Didn’t you know you were making those hit records?” I said, “If I knew that, I would be a multimillionaire” ... We didn’t really know, we were supporting our families.