Filmmaker Rebecca Miller takes on a tough documentary subject: her iconic playwright father; Merrill Garbus addresses cultural appropriation on Tune-Yards' new album; Aaron Sorkin’s Broadway adaptation of "To Kill a Mockingbird" hits a legal roadblock from the estate of author Harper Lee.

Merrill Garbus of Tune-Yards confronts cultural appropriation accusations

Singer Merrill Garbus and bassist Nate Brenner make up the band Tune-Yards. And, in case you don’t know, they’re white. That’s important to point out because the band’s sound may suggest otherwise.

The Oakland-based duo has always used complex, African-derived rhythms as the backdrop to Garbus’s piercing voice. Their indie, Afrobeat style has earned them legions of fans — but it’s also attracted fierce criticism.

In interviews, Garbus addresses the issue of appropriation. She has also taken breaks from her career to reevaluate the group’s direction.

Since Tune-Yards’ last album in 2014, she started DJ-ing to reboot her musical perspective and she even enrolled in anti-racism workshops.

"I don't want to be making a 'statement.' It's an exploration. In fact, the way that the music interacts with the lyrics is just as much a conversation as the lyrics themselves. And that's where I love songwriting because that's that magical interaction. It's the conversation between those elements that makes it food for thought."

The band recently released its fourth album, "I can feel you creep into my private life." It’s the duo's most challenging work, musically speaking. It also shows Garbus addressing appropriation and systemic racism in the songs themselves.

'Arthur Miller: Writer' — A daughter remembers her beloved complicated father

"Arthur Miller: Writer" is the sixth movie from writer-director Rebecca Miller ("Maggie's Plan"), but in some ways it's also her first.

More than two decades ago, she began filming her famous father around his home in Connecticut and recording conversations with him in his woodworking shed. She had decided that the man she knew — who she called "Pop," who told jokes and spun her around the backyard as a little girl — wasn't the same man she saw in public interviews.

Rebecca Miller was born in 1962, well after her dad had established himself as a great American playwright — impacting public discourse with plays such as “Death of a Salesman,” for which he won the Pulitzer Prize, and “The Crucible,” which used the Salem witch trials as a veiled commentary on McCarthyism.

Rebecca's mother was the photographer Inge Morath. As Arthur's third wife, she came along after his very public marriage to Marilyn Monroe, which itself has been preceded by a first marriage that had also ended in divorce. Rebecca Miller examines all of the personal and professional aspects to her father's life in the documentary.

She told The Frame that during the long process of making the film, she came to understand what motivated him and his work:

I think he was really primarily driven by a curiosity and love of people — human beings and how they worked, anomalies in their characters and how [someone] could be a good person and do bad things, or how people were morally ambivalent. He never taught people how to live. It's funny — he's thought of as such a moralist, but if you really unpack his work he's asking questions about what it is to live a moral life. But he's not really giving anyone advice. I think it's more like he's saying, Let's examine ourselves in some way.

INTERVIEW HIGHLIGHTS

In the film, Rebecca asks her father about fatherhood and he tells her that he "couldn't be a father 24 hours a day, I was in and out of my own skin." She explained his answer this way...

He had the challenge of anybody who's doing work that's very internal. To be present. And I was trying to imagine myself answering that question, saying, I couldn't be a mother 24 hours a day. I was in and out of my own skin.' To some degree everybody is in and out of their own skin, everyone is lost in thought, everybody's distracted. You're never constantly 100 percent present with your kids. But I think that some of that had to do with his being a father versus a mother. It had to do with being a completely committed artist. But he also was a different father, as could be expected over the course of his long life. And he had three marriages. And so the different children had slightly different experiences.

Rebecca Miller made use of her father's love letters and journals in the film and it wasn't always comfortable:

There were times when I found it disturbing or embarrassing. Like I shouldn't be there. There were certainly times where I was [almost] re-creating love scenes. Or kind of early love scenes ... where I felt quite uncomfortable in a way. But it was my job that I'd taken on. And that's when you have to try and see it in a more dispassionate way as a storyteller. But at the same time, one of the things I've been struck by is how different he seemed as a very young man right after the whole hit of his huge success, especially after "[Death of a] Salesman," where he was awarded almost demigod status for a minute there. And then later where he has a much more equivocal and humble way of talking. It's really interesting sort of seeing in a way how his persona changes.

Rebecca's parents had a son who was born with Down Syndrome. They decided to take the advice of having him raised in an institution. Rebecca discussed what her relationship with her brother, Daniel, has been over the years.

Over the last 20 years or so I've had a very fun relationship with him — a very easy one. When I was a little kid ... it wasn't easy for [my parents] to talk about. And I think that it was a lot of probably ambivalence about a decision [to institutionalize someone] that was culturally pretty common, but still fraught. As I say in the documentary, weirdly I know much less about what was going on in their minds than I might because I didn't get to talk to them about it.

When asked if this was the hardest subject to discuss with her father:

It was the hardest thing for me ... Because if you're trained not to bring something up for a really long time, then it's hard to bring up if that's what your culture is within a family.

"Arthur Miller: Writer" debuts March 19 on HBO.

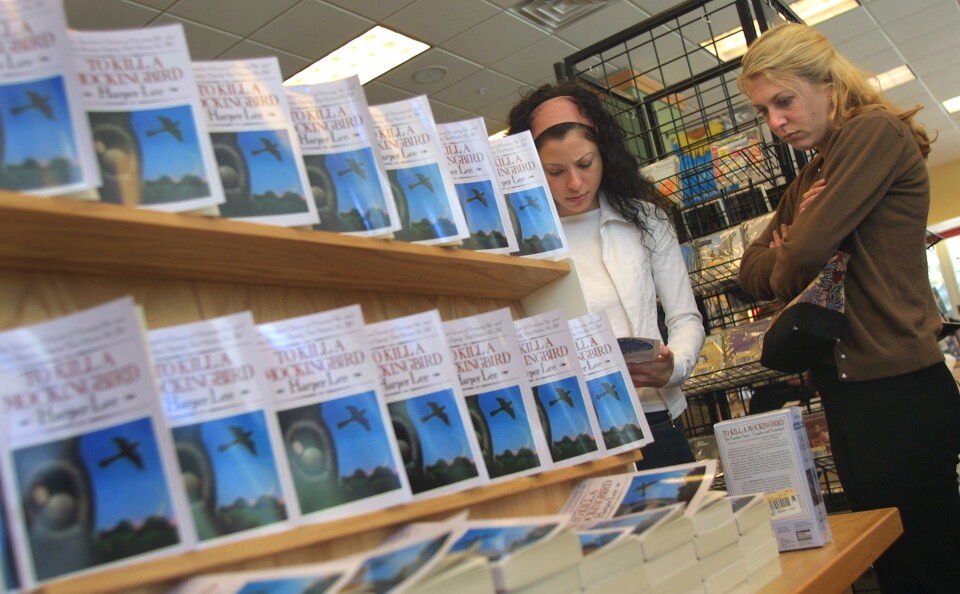

Harper Lee sues Aaron Sorkin over 'To Kill a Mockingbird' adaptation

Before Harper Lee's passing in 2016, screenwriter Aaron Sorkin and producer Scott Rudin received her blessing to go forward with their Broadway adaptation of "To Kill a Mockingbird."

The play is supposed to debut in December of this year.

But the author's estate has filed a lawsuit claiming that Sorkin's adaptation deviates too far from the spirit of the original novel. Sorkin's decision to add characters and manipulate existing ones didn't go over well.

Assuming no compromise is reached, the case will head to court in Alabama, the estate's jurisdiction, where a judge will assess the spirit of the novel and whether or not the Broadway production has strayed from it.

The Frame's John Horn spoke with New York Times theater reporter Michael Paulson about the lawsuit.

What the Harper Lee estate is upset about:

They're suggesting that the characters have been changed in ways that they find to be unacceptable. In particular, the two kids — Scout and Gem — are being played by adult actors. So, this is shaping up to be a sort of memory play where these adults reflect back on experiences in their childhood, and the estate sees that as a problem. And, more significantly, the character of Atticus Finch, who the estate claims should be seen throughout as a hero, in the play he evolves. He starts as a naive apologist for his neighbors and becomes more of a champion as the narrative unfolds. And the estate has a problem with that as well.

Sorkin's decision to include two characters that weren't in the novel:

The play focuses on a specific section of the novel. A significant section — the trial — has a couple of new characters. And also the housekeeper, Calpurnia, has more of what we might call agency. She's a little more outspoken in the play than she was in the novel, reflecting the way that writers in 2018 think African-American characters ought to be represented.

Producer Scott Rudin's response to the complaints:

He completely rejects the suggestion that they have departed from the spirit of the book. He says that the play, which is still being developed, very much honors the spirit of the book [and] that, of course, it is different from the book. That it is not a bunch of actors on stage simply reciting Harper Lee's words. It's a theatricalization of a significant section of the novel, and that Harper Lee knew when she agreed to give the rights to this producer and this writer.

Does the book need an update for contemporary audiences?

The estate at the moment seems quite dug in with the notion that the characters should be exactly the same as the ones in the book. They don't seem all that interested in the imperatives or arguments about contemporary theatre or contemporary audiences, or the differences between something you might see onstage and something you might read in a book. They tried to negotiate this both in person and in email for some weeks before they finally had a breakdown this week and the estate filed suit.