Robert Mapplethorpe gets a massive retrospective at two L.A. museums courtesy of the Mapplethorpe Foundation. Can a set top box that streams first run films the day they're in theaters disrupt the movie business as we know it? Closing the gender gap one women artist at a time.

Why it took so long for Robert Mapplethorpe to get his first major LA show

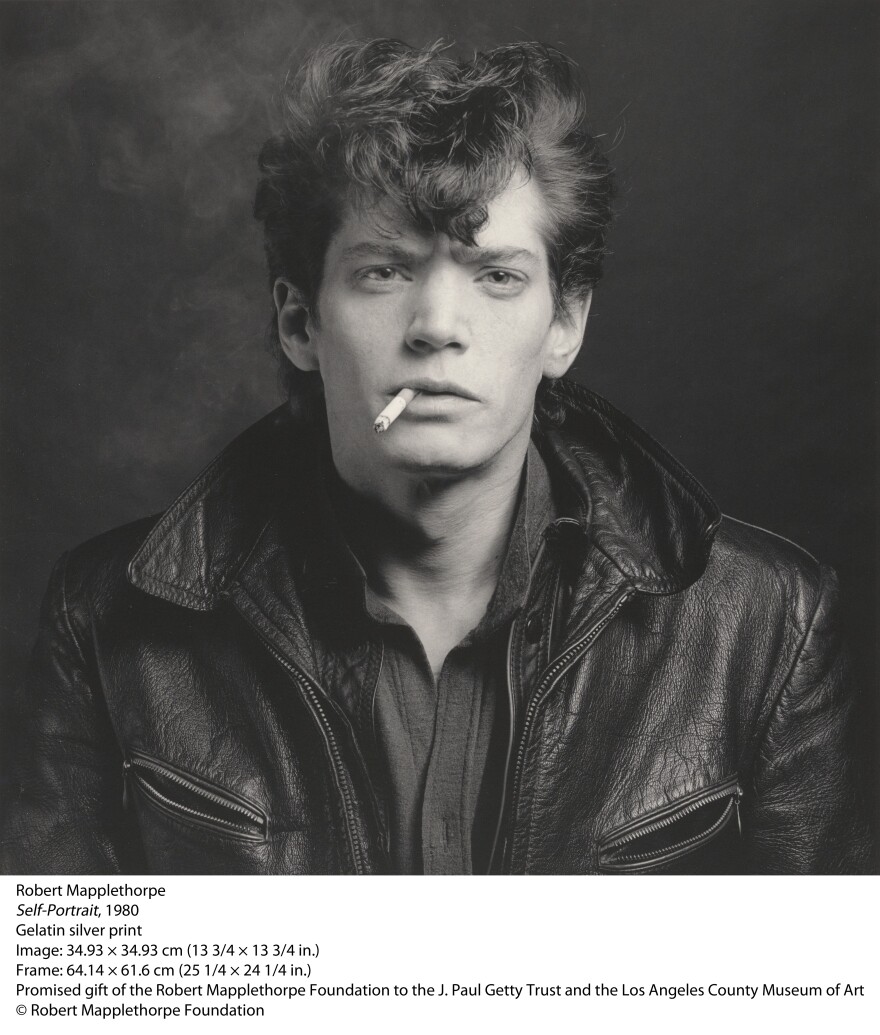

Obsessed with form, Robert Mapplethorpe was an exacting portraitist, still-life photographer and documentarian of the gay leather scene in 1960s and '70s New York. But to many modern viewers, he's best remembered as the photographer whose art went on trial.

In 1990, his work sparked a major controversy over government funding for the arts. It also led to the first trial in which obscenity charges were brought against a museum director, Dannis Barrie of the Cincinnati Contemporary Arts Center. Barrie was acquitted and Mapplethorpe’s work has only grown in stature and influence since then. But his work has never received a major show in Los Angeles — until now.

LACMA, the Getty Museum and the Mapplethorpe Foundation have teamed up to present an enormous retrospective called “The Perfect Medium," a title that riffs on Mapplethorpe's infamous touring show "The Perfect Moment."

When The Frame's John Horn met with The Mapplethorpe Foundation President Michael Ward Stout, he began by asking: What took L.A. so long?

INTERVIEW HIGHLIGHTS

Why is it that someone as important as Robert Mapplethorpe never had a show in Los Angeles before?

Mapplethorpe died in March 1989. In June, suddenly, this controversy arose in Washington involving the famous senator from North Carolina, Jesse Helms, and the Corcoran Gallery, which canceled an exhibition which had been touring from when Mapplethorpe was still alive. There ensued this tremendous controversy about the National Endowment for the Arts, and government funding for the arts. There was so much Mapplethorpe on the news.

By April 1990, that exhibition was still traveling. It traveled to Cincinnati, where there was another type of big controversy. The museum director was arrested for promoting obscenity and pornography. There was a famous trial.

All the sudden there was too much Mapplethorpe. Certain museums wanted to have Mapplethorpe exhibitions because they wanted to exploit this attention. We, [The Mapplethorpe Foundation], started to say no.

They were just trying to make headlines.

I think so. I wanted to concentrate on Europe. So we started to say 'no' frequently.

I want to know more about your relationship to Robert Mapplethorpe. How did you know him and what was important to him about what happened after his death?

I knew Mapplethorpe just from being approximately the same age, being in New York and being part of what we still call the art world. I was a lawyer working with artists. I was a person who very often went to the famous Max's Kansas City restaurant and bar. Robert was there, often with Patti Smith. But I didn't know him well.

In 1980 or 1981 he contacted a mutual friend and a client because he wanted to work with me. He felt that because I'd represented Salvador Dalí for a number of years, I must be very connected in Europe. He was interested in licensing his designs. And then we became friends in that process.

When he became ill — he was diagnosed with an HIV infection, pneumonia, in fact — in September 1986, I was in Geneva. He called and said, I have it. And I'm probably going to die. You have to come home right away. Which I did. By the time I got home, he was recovering. And then we started to talk about his estate plan, which fascinated him. He never thought he would die. Since he had no family goals in the estate plan, we talked about a foundation.

Anyone who knows Mapplethorpe knows he was a New York artist. And yet the Foundation's massive 2011 gift of his work was to the J. Paul Getty Trust and the Getty Museum of Art. How did this New York artist end up having all of his work in Southern California?

There's nothing about a geographic location that should dictate where you should put someone's life work, particularly when they consist of materials that are difficult to care for. Generally, there aren't many archives connected to museums which have the capacity to care for photography.

In terms of storage, of archive?

Right. There are fewer than five in the United States, and the Getty is by far the most equipped. However, the Getty doesn't have contemporary museum exhibition programming, and Mapplethorpe thought of himself as a contemporary artist. Therefore, LACMA is a partner in this joint venture.

Is there some part of the exhibit that you're particularly excited about, that illuminates the way in which he saw himself as an artist?

Robert Mapplethorpe has become very well known for what people call his sex pictures. Right now the Getty is exhibiting something called the X Portfolio, 13 very strong, difficult pictures of homosexual sex acts. It's also being shown in Oslo. And while that's interesting and it draws big crowds, Mapplethorpe's total output of that subject matter I don't think is more than 30 pictures. The total number of images which he chose to created his limited editions are more than 2,000.

Unfortunately, people know the sex pictures well. It's unfair to the artist. He created that work within a year-and-a-half period — it started to bore him, actually — and he moved on. And he became a great portrait artist and still life artist, even a documentarian. Everyone wants to see those sex pictures and they will, but people should take a good look at the great portraits he took, and the beautiful flowers and still lifes that are in both [the Getty and LACMA] — and lighten up a little about the sex pictures.

"Robert Mapplethorpe: The Perfect Medium" opens on March 20 at LACMA and runs through July 31.

Feminist edit-a-thons work to close Wikipedia’s big gender gap

A quick Google search of Boyfriend, a New Orleans-based rapper and performance artist, turns up tons of articles and videos — but no Wikipedia page. It's one of the many holes in the site's vast repository of knowledge.

Music writer Julie Farman wants to fix that.

A seasoned Wikipedia editor, Farman has been fact-checking and adding to the site since about 2012. Rather than ignore mistakes, she learned how to edit and began making corrections herself.

Only 13 percent of Wikipedia's editors identify as female. That may explain some of the site's knowledge gaps, which are more frequent and pronounced when it comes to female musicians and artists.

So Farman is creating a Wikipedia article for Boyfriend.

“She’s really fascinating,” says Julie. “She has this great big history and I’m always excited when I find a subject that hasn’t been written about. Especially when it’s someone like this woman who has reams and reams of press, and it’s like, ‘Wait. Why isn’t she in here?’”

Julie’s not working alone. She’s at a Wikipedia edit-a-thon, which is exactly what it sounds like — a group of people who come together create Wikipedia articles or add to existing ones. Some are veteran editors; others are here to learn.

This edit-a-thon is co-hosted by LACMA and the Art + Feminism initiative, and these editors are here to increase the representation of female artists on Wikipedia.

Longtime Wikipedia editor Stacey Allan, the organizer of this event, is excited about helping others learn. She’s been organizing edit-a-thons since 2013 through a series called Unforgetting L.A., which focuses on Los Angeles art history, especially on overlooked artists including women and people of color.

“It’s a mix of people, but they usually come with the goal of righting a wrong. They will come with someone in mind that they were shocked to find didn’t already exist on Wikipedia, and they want to make sure they correct that today,” Allan says.

That describes first-time editor Tracey Payne.

“One of my good friends from a long time ago, her name is Judy Brubaker," she says. "Wonderful actress back in the '50s. She’s mentioned but there’s nothing about her. So I’d like to maybe create a page about her.”

Omissions like this one aren’t uncommon. “Anyone can edit Wikipedia, but the studies show that not everyone does. Fewer than 13 percent of editors identify as female,” Allan says.

Wikipedia runs on an army of volunteer editors for whom it’s a hobby or a passion project. People work on the subjects they're personally interested in. More female editors should mean greater representation.

“There are a lot of things that determine how histories get written,” Allan says. “We don’t always have the opportunity to participate in that writing. If you can find information about [female artists] online, then they truly exist in the world and can’t be ignored. It’s a way of remembering.”

Would you pay $50 to watch a movie on your TV? Napster's founder thinks you will

How much would you pay to watch a blockbuster movie from the comfort of your couch on the same day it comes out in theaters? How about $50?

Thanks in part to Sean Parker — the man who disrupted the music business with file-sharing service Napster — we might be able to do that.

A startup called Screening Room reportedly has a piracy-proof set top box and a growing list of Hollywood studios, filmmakers and theaters interested in bringing big movies directly to the small screen.

Brent Lang, a senior film and media writer for Variety, recently wrote about Screening Room. He spoke with The Frame’s John Horn.

Who might a service like Screening Room appeal to?

...There’s this sort of age around the time that people have children — of between mid-30s and mid-50s — when people just sort of stop going to the movies as frequently. And what this technology would in theory do is allow studios to capture that audience and, advocates for the Screening Room suggest, grow the movie business.

Are there any theaters showing interest?

Well, it sounds as though AMC is the most interested in this proposal, which is not surprising because they’ve been the theater that’s most willing to experiment. But other exhibitors such as Regal [Cinema] apparently are not interested in this plan, at least not yet. And as you say, some people feel like something like this would, in essence, be midwifing their own demise... You could encourage people to not show up at the theaters anymore.

One of the things that’s been interesting to see is some of the bigger Hollywood names getting behind this: J.J. Abrams, Steven Spielberg, Peter Jackson. Why do you think these filmmakers are making a bet on a technology which could in theory keep theatergoers away from the multiplex?

Well, I can’t speak for all of them, although Peter Jackson did come out and confirm his involvement. But, you know, when you look at how the movie business is currently constructed, it’s quite interesting, because while domestic ticket sales reached $11 billion for the first time last year, fewer films were responsible for a greater percentage of that income. So what you have is a real case of haves and have nots. You have a very few films like “Deadpool” or “Zootopia” doing monster numbers and you have a lot of movies that are falling through the cracks. And maybe something like a Screening Room — I’m not sure [but] perhaps these filmmakers reason — could provide a business model forward for films that aren’t about superheroes or comic book characters or transformers and allow them to have a viable business model.

What are some of the major studios thinking about this?

Well, right now, officially it’s a very firm “no comment.” But we have heard that several studios are very interested. So far the only studio that we know that is firmly a "no" is Disney. And that makes a lot of sense because the kinds of movies that Disney produces are all these tentpole blockbuster movies — Marvel movies, Pixar movies — that don’t necessarily need to get the kind of older audience that Screening Room would cater to. And Disney cannot run the risk of angering exhibitors and potentially losing theaters for their major film releases.