Paul Dini went from writing Batman stories to mining his own traumatic history in the graphic novel “Dark Knight: A True Batman Story;” NBC goes all-in on Summer Olympic coverage like you've never seen; Inside a bootcamp for Broadway dreamers with pros like Taye Diggs

NBC going all out for Summer Olympics coverage in Rio

When the Summer Olympics take place from Aug. 5-21, NBC will be all Olympics, all the time. Even "The Tonight Show with Jimmy Fallon" and "Late Night with Seth Meyers" will be replaced with live broadcasts from NBC studios on Rio de Janeiro’s Copacabana Beach.

Unlike recent Summer Olympics in London and Beijing, Rio de Janeiro's time zone is just one hour later than eastern time in the U.S. — a fact that NBC intends to exploit. NBC will air 260 hours of Olympic programming, with an unprecedented 6,700-plus hours spread across NBC Universal’s cable networks. Add to that the 4,500 hours of live-streaming digital coverage, one can only imagine the flood of up close-and-personal, tear-jerking athlete profiles there will be.

To get more of an idea of what NBC is thinking, The Frame's John Horn spoke with Brian Steinberg, senior TV editor at Variety.

Interview Highlights

This year’s Olympics are not several time zones away. So what does that mean in terms of people watching the games in real time, not the next day or in the middle of the night?

I think you'll be able to see more of what you want at times where you might be awake to see it, as opposed to Beijing and London, where NBC more or less put them online to stream live and collect highlights during prime time for people to watch.

That's part of the problem, and it will still be a bit of an issue on the West Coast, that in past years, by the time an event got to prime time, if you paid any attention to social media or the news, you knew what the results were. I think NBC feels like that has been a huge problem. Do they have a benefit now of people watching more live events than in years past?

I think so. I think this will give an added heft to prime time. They also are more or less removing the schedule for two-and-a-half weeks. All you're going to see is "The Today Show" and [The Nightly News with] Lester Holt, and everything else is going to be Olympics. You'll have a late night show with Ryan Seacrest instead of Jimmy Fallon and Seth Meyers. I think since they're paying a lot of money for the rights for this thing, they're blowing it out on the broadcast network and also on many of their cable networks, on digital and on their Spanish stations as well.

Why is there so much content this time around? If you look at the total coverage, it's thousands upon thousands of hours. What is NBC's play here?

First of all, there's a lot of technology available now that lets them transit more of this stuff when it happens, as opposed to 20 years ago when something would happen in Nome or Beijing, wherever it was being held, and they'd have to have a way to collect it and distribute it. Now you can watch it in real time, and if you're interested you can watch it at work. I think the notion of waiting to see the highlights later on in the evening is kind of an anachronism and no longer really part of the behavior of a rising generation of TV viewers.

Let's talk a little bit more about digital. NBCOlympics.com and the NBC sports app will live stream — and I'm not making this up — 4,500 total hours. So what is the overall digital plan and does it include some virtual reality?

There is some chatter about virtual reality and 4K HD as well. They haven't spilled the beans, but they are hinting that they're going to try it. I think there are just multiple behaviors in how people watch video these days and so if you're NBC or you're CBS or Disney, you need to dip your toe in all these waters and do it right away.

NBC Today Show anchor Savannah Guthrie is skipping the games over Zika virus worries, and many of the top golfers — including Jason Day — won’t compete. NBC spent more than $1.2 billion to get these games. With worries about athletes’ and visitors’ safety, is NBC maybe more nervous than they have been in years past?

I think they have to have security on their minds. Savannah not going is a big deal. That is a very recognizable face and one of their ambassadors for the network. The fact that she decided not to go says a lot about the danger of Zika and what it can do. But yeah, I do think that there has to be some kind of concern about the disease, and security. I'm sure these guys already have a pretty big security presence at the Olympics, but I do think this adds another wrinkle to the whole situation.

Live sports is one of the very few events on television where people don't use their DVR to fast forward through commercials. How much advertising revenue has NBC been able to book so far for this summer's games?

I believe they said in the past they booked over a billion dollars for this event. That's been a benchmark for them in the last couple of Olympic showings. They said they intend to go past it this year. They usually get a couple of major Olympic sponsors and then the network tries — after going to the International Olympic Committee — to go with its own clients and suss out different category exclusives of certain kinds of auto makers or banks. You generally will see the same ads several times over the course of those 16 days.

3,000 miles from Broadway, dreams stay alive for The Great White Way

Inside a rehearsal room at The Wallis Performing Arts Center in Beverly Hills on a recent afternoon, it’s hard to imagine that the women practicing a song from “The Color Purple” musical have much to learn about performing. They already sound amazing.

But skill-sharpening is exactly why they’re here. All are students of the Broadway Dreams Foundation. It’s a group that’s been teaching week-long performance intensives for 10 years across the country — even around the globe in places such as Moscow and Brazil. You can think of it as a “Broadway bootcamp” of sorts, where people of all ages, experience and skill-levels learn to be better “triple threats.” That means they can act, dance and sing.

“I’m a Baptist preacher’s daughter, so I’ve always sung. I’ve always been musical,” says Marva Smith, a student in the program. While music has always been a part of her life, it wasn’t until recently that she realized this could be her job. She's spent most of her adult life as a community organizer.

“I didn’t start acting until I was 45,” Smith says. When asked how old she is now, Smith says: “51, honey! This is what 51 looks like.”

Just recently, a friend at a BBQ overheard Smith singing. The friend told her about this intensive workshop happening at The Wallis and that there was no age restriction. Smith knew she had to come and follow her Broadway dreams.

“I’ve learned a lot,” Smith says. “I can sing. But these folk can sang!" And so life begins again. You just gotta hit the reset button!"

Stage and screen star Taye Diggs teaches dance at the workshop. Diggs says the younger students in the workshop are just as talented as the adults in the class, and they might even have a leg-up.

“They got more going for them than I did,” Diggs explains. “It’s really empowering and exciting. I think young artists are more in touch with themselves. They are less ashamed. They are more confident. They didn’t have a lot of the hindrances that people my age had coming up.”

Those are some of the big ideas at the Broadway Dreams workshop: To be less ashamed, more confident and less nervous. The students here quickly learn that those qualities not only build a stronger character, they also build a stronger performance, which all requires some strong, thick skin.

In another rehearsal room, a teenager named Grant sings in front of the class. The instructors listen and then one shares this feedback: “I think technically you do a marching band thing with your foot. Did you notice that? That’s just nerves.”

Grant is listening to notes from Olivier-nominated theater director Stafford Arima, whose recent Broadway credits include "Carrie: The Musical" and "Allegiance." Arima says these students are smart and eager to learn, so his class is nothing but real talk. In fact, the class is actually called, “Do you know want to know the truth?"

“This is an actor’s song,” Arima explains to Grant, the young singer. “This is a storytelling song. This would reveal to us, Can you act? Can you take us on a journey? And if you can’t yet because you are not ready, maybe it’s too early for you to tackle this song.”

But in the rehearsal room next door to Stafford’s tough-love class, you’ll find students trying to tackle all kinds of tricky songs — sometimes very successfully, sometimes it’s more of a challenge. Voice teacher and former "American Idol" star, Isabelle Pasqualone, works with the students on combining technique and craft with their willingness and passion.

Pasqualone recalls: “I wish someone would have told me, ‘Go into a room, and sing something you are so comfortable with!’”

While Pasqualone is now an accomplished performer and teacher, 10 years ago she was a student taking these Broadway Dreams classes. So she knows about nerves.

The attentive students tap fast notes on electronic tablets as she advises: “Don’t go into a room and sing something you think they want to hear, or you think is right at the moment. Sing something that you love to sing and that you connect with. Because, ultimately, when someone walks into an audition room, everyone who's sitting at that table is either tired, hasn’t had their coffee, or is just wanting to feel something. And if someone comes in and really connects to a song, that’s all anybody every wants.”

The days are jam-packed. Program participants dash from Pasqualone's voice class to the movement studios of choreographers Alexis Carra and Jenny Parsinen. Then they shuttle outside for private one-on-one coaching with Broadway newcomer Ryann Redmond or acting intensives with Craig D’Amico. It’s a really tight schedule. But they only have one week to learn from Broadway’s best.

The delightful, supportive environment keeps spirits high, and yet, while many students qualify for financial aid, access to Broadway’s crème de la crème hovers around $900. Of course, there’s never a guarantee of success in the hardscrabble life of a theatre artist.

Annette Tanner is executive director of Broadway Dreams. Tanner, who co-founded the program, says, “Many of them, I don’t believe, will ever go on to being on Broadway. It’s a highly competitive field. But we’re giving them tools that really aren’t offered in schools today. We’re providing them with courage and empathy and how to look at each other — things that kids in this generation really, really need. Everything we do is based in love. It’s just a beautiful thing.”

Many students agree with Tanner. Some even come back more than once, such as 17-year old Jai’len Josey from Atlanta. This is Josey’s third time at Broadway Dreams.

“I’ve always had those family members that will [say], What if this doesn’t go as planned? What are you gonna do? And I’m stuck with the Plan A/Plan B type thing," Josey says. "My Plan A is to perform for many. And my Plan B is to make sure that my Plan A happens.”

But the best plan of all, according to Taye Diggs, might actually spring from the most personal place.

“It would be to get out of your own way,” Diggs says. “It’s not like there aren’t hurdles. But it’s all perspective. And I think when you are an artist, the more positive you are with yourself, and accepting, the better.”

How Batman helped Paul Dini overcome a traumatic childhood and being mugged as an adult

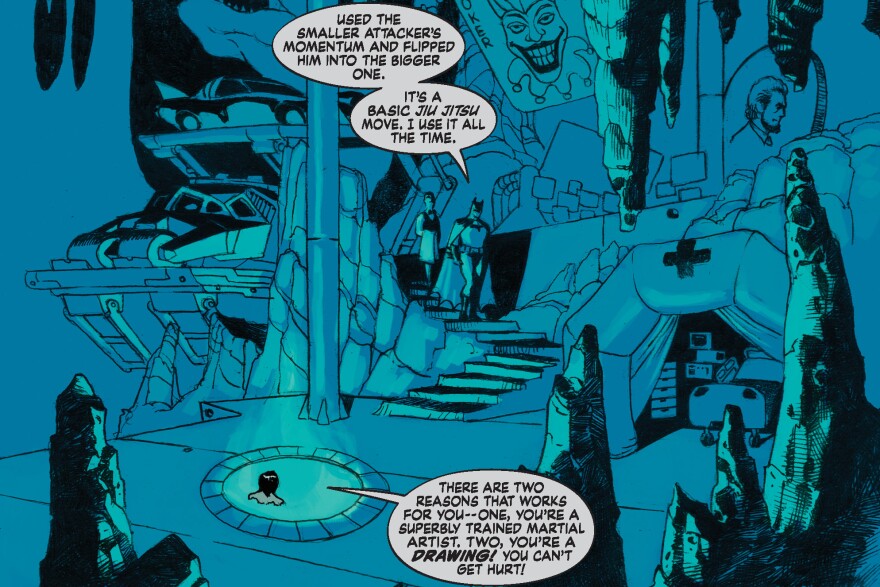

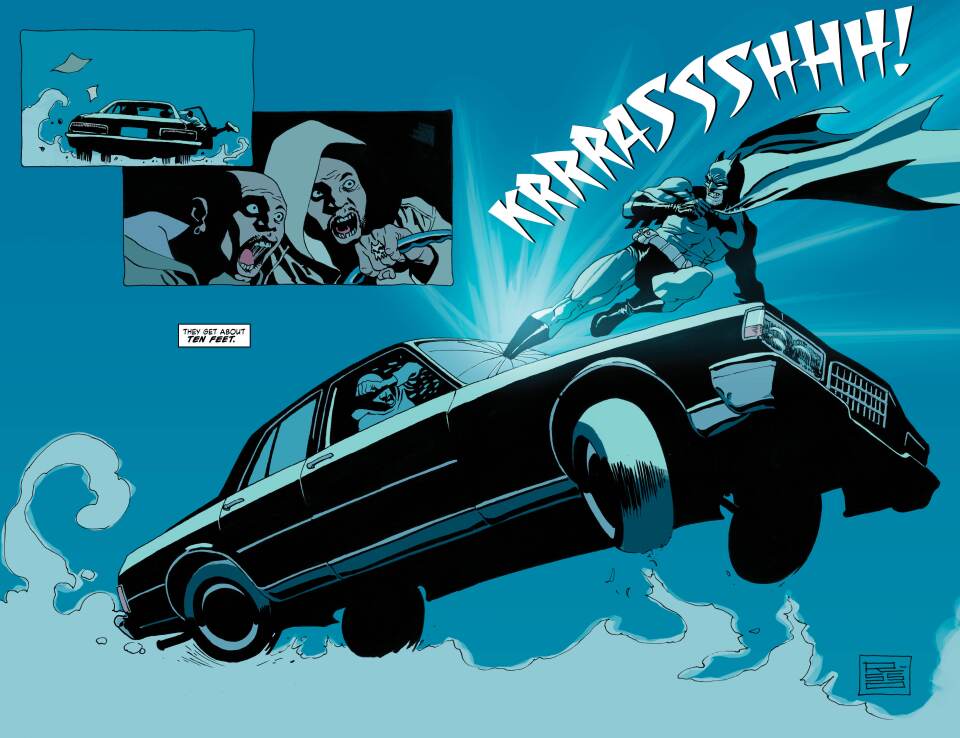

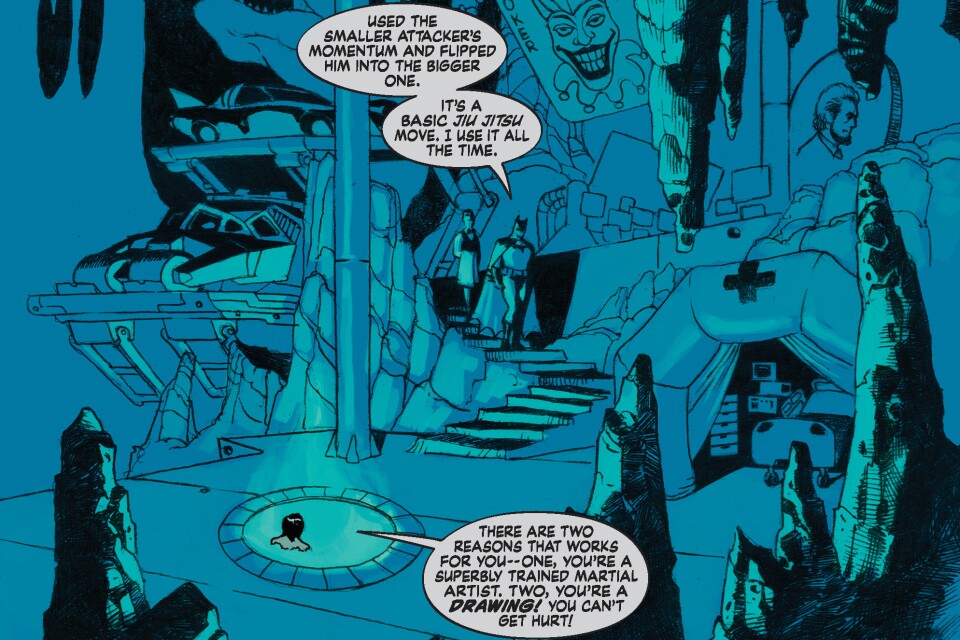

Paul Dini is a talented writer and lifelong fan of superheroes. He combined those two passions to become a screenwriter and comic book writer. His TV credits include “Batman: The Animated Series,” “Tiny Toon Adventures” and even “Lost.” With Bruce Timm, Dini created the character of Harley Quinn, an iconic Batman adversary coming to the big screen this summer in "Suicide Squad."

But Dini is also a crime victim. He was mugged and badly beaten in 1993, but the suffering he endured at the hands of others began well before that. As a child, he was regularly bullied, and from an early age, he would retreat into his imagination.

When Dini joined The Frame, he discussed his new graphic novel “Dark Night: A True Batman Story,” in which Dini writes about his childhood, his beating and his road to recover his self-esteem.

Interview Highlights

This book is really about an assault in 1993, but I want to talk about the assaults that preceded it. To me, those are as harrowing, if not even more harrowing, and they occurred when you were repeatedly and violently bullied as a child. Can you talk a little about what happened to you when you were a kid?

It just seems to have been something that happened that dovetailed with my first school experiences. I remember very vividly going to school, being very happy, and then just having guys there who were just out to make my life miserable.

I remember showing up one day with a toy that I'd gotten — I had sent in some cereal boxes and I'd got a stuffed toy — and I wanted to show it off to everybody at school. So I get there and the door's closing, and there was this one guy, I don't even remember who he was, but he stood outside and said, "You're not going in," and he knocked the toy out of my hand and closed the door and locked it. I couldn't get in, and I'm sitting there while he's smiling, and I went home crying that day. That might have been where it started.

How old were you?

Four? Four or five.

So you write in the book about becoming what you call "an invisible kid," and you illustrate a scene where there's a school bus and you're getting beaten up in the back of the bus. Can you read a little bit from this page of the graphic novel?

Sure. "So you get the idea. In order to survive, I devised this unique coping mechanism. I could put up with any sort of mindless torture in public, as long as I could let my imagination run wild in private."

It's a horrible way to get from point A to point B, but is it fair to say that the way in which you were treated and how you saw yourself as a child led you to become an artist?

Yes, definitely. And I think that, if there was anything healthy about that that I could teach myself, it was to direct that anger at something to create something positive. A lot of people grow up being bullied and they say, "I'm directing that anger at the people who bullied me, I want to get even, I want everyone to know how bad I feel."

It's wrong to become a bully yourself or to take it out on other people, and in my case, I just retreated to a place where I was safe. And that place was my imagination, books, and television.

And there was clearly something that meant a lot to you about Batman. By 1991, you're working on "Batman: The Animated Series," and you've worked on other Batman projects in the years since. What is it about Batman that really inspired you and attracted you to the character?

He was a character that had always been sort of around, and then suddenly the TV show and everybody's talking about it. I remember I really wanted to see the first episode, and my father, Bob Dini, was a singer in the '50s. He said, "Oh, I performed with this guy Frank Gorshin, and he's in this TV show tonight." But we didn't get channel 7 very well, so I had to go over to a friend's house, and I watched the show and saw Batman and the Riddler for the first time.

In those first episodes, Batman was really cool — he had the car, one of the henchwomen died in the episode, and it seemed like a fun world that was also darker than something like the "Superman" reruns I'd been watching in the afternoons. I enjoyed the character, but then I fell out of it, and the more they began making the show gaggy and campy, the less I watched it.

But a few years later, I was really gravitating toward the comics by Neal Adams and Denny O'Neil. I thought, Oh man, the character can be strong, powerful, dark, and mysterious. Why didn't they do this on TV? This would've been cool.

In the graphic novel, there are a lot of conversations that you relate with therapists, and what they're telling you to change in your life. And you generally don't listen. Does the act of writing this book serve as some sort of therapeutic event itself, even if it happened so many years after you were mugged?

Yes it does. When I told people I was writing the book, some people said, Why are you doing this? Is it some sort of therapy? Yes and no, but I also feel like it's a story I'd been thinking about a lot, and I think that I could tell it and maybe people would get something from it. It was kind of like ripping the lid off Pandora's box again — I had to deal with stuff that I'd internalized over the years. But once I took them out it was like, Yeah, this is still nasty, but I don't need this anymore. I was able to mentally clean house quite a lot while writing this.

When you were mugged, you were working on the animated movie, "Batman: Mask of the Phantasm." And after you were mugged, you find yourself essentially unable to write Batman stories, and in the introduction to the graphic novel, you write, "The last thing that made sense to me was to continue writing stories about a fantasy crimefighter." Why was that?

Because it was like a horrible joke. In these stories, there's some sort of justice that comes to the characters — either Batman is able to stop a criminal and bring them to justice, or that villain dies, perishes, or is defeated as a result of something they've done. And Batman's the mitigating presence, the one who brings justice. Justice is served because he's there.

In this case, it was like I couldn't write myself a happy ending out of this. I couldn't even write an ending to this, because everything I did after the attack — trying to get more information out of the police, trying to go to a couple help groups — was met with... there was no solution to it, nothing happened, nothing came of it. It was a bitter joke, like, OK, I have to write a happy ending for this guy? I have to tell an untruth, knowing that there was someone who was victimized and there won't be any help for him.

But then, through talking to other people and examining where my life was, and hearing how much people liked the things I'd worked on, it was like, Well, you're not doing this for yourself. You're doing this because it maybe helps someone else's day get a little better, so you should keep doing this.

One of the things I was most struck by in this novel is your relationships, which is probably too strong a word, with women you name Vivian and Regina. These are women you go out with, but it's clear they're not interested in you in the way you're interested in them. Can you read two pages of dialogue from the book for us? This is what you do to yourself after Regina decides not to attend an Emmys ceremony with you because it's not going to be televised.

Sure. Oh boy, OK. "She forced you to look at yourself as you really were. With all your imperfections and inadequacies laid bare. What does she see that she hated so much? At every place you saw imperfection, you left a little mark, confirmation of her judgment on you. Of course, she never really hated you; probably never liked you much either, but my guess is she rarely thought about you at all. Even that would have required too much emotional investment. The only hatred you experienced was from yourself, because in that moment, you looked at yourself and despised what you saw."

Can you describe the images that are on those pages?

Yeah. I'd gone to the Emmys with the crew of "Tiny Toon Adventures," and I had this date who basically blew me out of the saddle the day of the Emmys. I felt so miserable about myself and I'd idealized so much what I had felt this relationship was leading me to, that I took it out on myself. I stripped off my tuxedo, stood semi-naked in front of a mirror, and like I said, every time I saw something I didn't like or felt she didn't like, I took the wings of the Emmy and cut myself. In that moment, I was in love with the idea of bringing pain to myself and hurting myself as bad as I could for being a failure, for putting this image out there of someone perfect, and then I was the one who destroyed it for myself. So, you know, I look back on it, and it affects me to read the words more than it does to relive the event. Now I think the event is really kind of stupid and the person definitely not worth it, but I do empathize with that sad version of myself from years ago. Not only do I want to be more comforting to him, I just want to say, Schmuck! What the f---? Take that Emmy, put it on the shelf, be proud of it, and never think about it again. But at that point, I was a creature of my own imagination and taking it out on myself.

We should point out the nice postscript, which is that you're here with your lovely wife, Misty, so it all gets better. And I'm wondering now, is the point of this graphic novel that it all does get better?

I mean, I'm leaving here and going home and writing a Harley Quinn cartoon. So the more things change, the more they don't. I'm still doing it, but I'm doing it because it's fun, it's pleasurable, people enjoy it, and it's where I want to be at this moment.