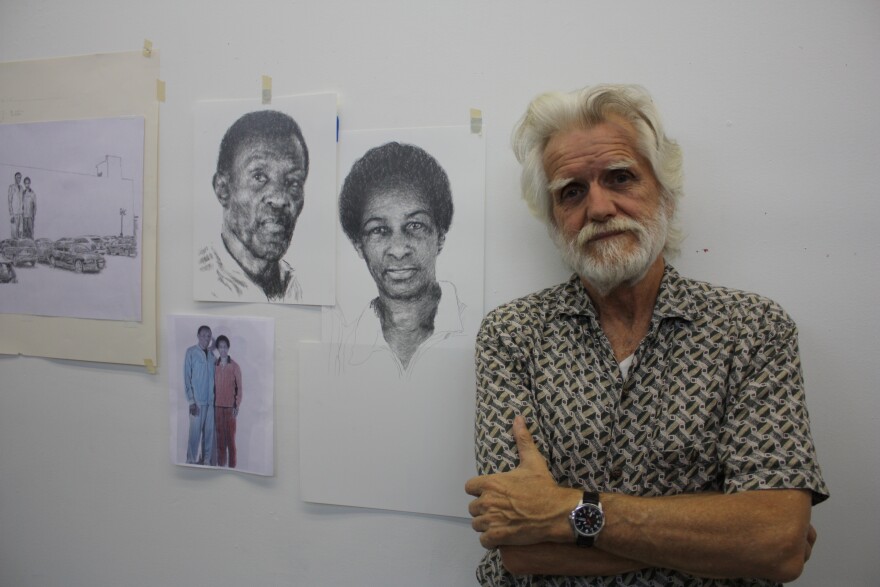

Noted muralist Kent Twitchell (pictured) has created a new work for the Special Olympics; playwright Todd Almond was inspired by Matthew Sweet's 1991 album, "Girlfriend," for his musical about growing up gay; the Teragram Ballroom tries to carve out a niche on the local live music landscape.

Teragram Ballroom aiming to be the next 'it' venue in LA

The '90s rock band The Dandy Warhols has toured the world, played to tens of thousands of people at music festivals, and headlined the 1,200-seat Wiltern Theater just a couple of years ago. But later this year, the band will be playing a venue that only holds 600 people on the outskirts of downtown L.A.

It’s a bit of a coup for the Teragram Ballroom — a new music venue recently opened by Michael Swier. He’s a prominent New York City club owner who started the Mercury Lounge and Bowery Ballroom there.

Swier spent more than three years and $3 million renovating what used to be a silent movie theater. The Teragram Ballroom opened in May with the alternative rock band Spoon selling out the venue.

The Frame's John Horn spoke with Michael Swier and Teragram Ballroom’s talent buyer, Scott Simoneaux, about why they chose L.A., how it differs from other venues, and why the city has a booming music scene:

INTERVIEW HIGHLIGHTS:

Why did you decide to make a new venue in Los Angeles?

Michael Swier: I personally have built venues in New York. New York is what I know and what I feel comfortable in. The thing that L.A. shares is the music industry and the demographic of the music industry. These two cities are the centers.

Like New York, L.A. is an incredibly competitive market when it comes to bands. Scott, there are 50 shows in L.A. tonight. So when you're putting together your line up and trying to set yourself apart from other venues, what is your pitch to get bands to come to your venue?

Scott Simoneaux: They get treated well. The sound is great. They're going to be playing a room in an important market where you're playing for media and you're playing for press. You got to make a good impression there. Part of it too is — you've seen what is going on downtown just over the last few years. Now you look at all the cranes downtown and you would think that we were expecting the Olympics.

That plays into it as well. I think not every single show is going to cater to people who live in Silver Lake, Echo Park, Los Feliz, etc. But a lot of that programming is the younger people or people who might be a little big more delved into the kind of stuff that we do.

How would you describe the kinds of bands that you want to have playing in your club? What is its identity going to be? How is it going to be different from other clubs and venues in LA?

Simoneaux: If you had to put it into a category, probably more indie than not. But I don't think we're going to be restricted on anything other than the focus will be live acts, as opposed to doing DJs, let's say.

You had Spoon play a night after they played at The Wiltern, which is a much bigger venue. Does that mean it is a different kind of show for a band? Even if they are used to playing larger clubs?

Swier: It becomes a bit more special when you can do "underplays."

Meaning like when U2 was playing at The Forum and they did a gig at The Roxy?

Swier: Exactly. That would be considered a bit of an underplay. Underplays don't happen often so there are some great examples. Metallica played at the Bowery Ballroom. I loved when Robert Plant played there. It was like I was reliving my childhood. He is playing some Led Zeppelin on my stage in this little intimate Bowery Ballroom.

The music industry is centered here. I see that happening here. I see predominantly our genre as being indie rock — the demographic, the type of people that come to see those shows, the passion they have. Just the sensibility, they're smart people that enjoy the music without having to get too active.

If people see the name Teragram Ballroom on print they would maybe see that there is a name hidden in there. Could you explain what the name means to you personally?

Swier: My wife Margaret passed away just over five years ago. She was an extremely integral part of our business. She was very hands on — finance, private events, human resources — she would take on everything.

So "Teragram" is Margaret spelled backwards. As time progressed it became more important to me because it was the first venue I didn't open with her. We didn't have children. Theses venues — there are certain ones that we really built from ground up — were our children. This would have been one of them. So it's happy-sad.

Michael, what is it actually like to open a venue? What does it mean to you both personally and professionally to see the audience coming in that first night?

Swier: It's indescribable. There is nothing quite like it. It is like a birth. It's special. You can really just look at the show. Look at what you built and what you accomplished — what was actually happening on there. Nothing really can describe it.

To see Teragram Ballroom's upcoming music calendar, you can head to the club's website.

Kent Twitchell paints larger-than-life Special Olympics heroes

You might not know muralist Kent Twitchell by name, but if you’ve spent any time driving around Los Angeles, you’ve seen his work. His eight-story tall portraits of L.A. Chamber Orchestra musicians stare down as you drive north through downtown on the 110, and his Freeway Lady is a local favorite.

His most recent project is one of three murals commissioned by Toyota to commemorate the 2015 Special Olympics World Summer Games in Los Angeles. Twitchell was given no specific instructions, but he says that deciding who to paint was easy.

“I asked for the most iconic figure that would represent the Special Olympics and everyone came up with Loretta Claiborne, who was a past champion and just is one of those charismatic, wonderful kind of people,” Twitchell said. “Rafer Johnson, of course, is one of the greatest athletes of all time."

(Twitchell's sketches for his Special Olympics mural hang in his Downtown Los Angeles studio. Photo Credit: Elyssa Dudley)

(Twitchell's sketches for his Special Olympics mural hang in his Downtown Los Angeles studio. Photo Credit: Elyssa Dudley)

Visiting the mural site is usually the first part of Twitchell’s process. He sketches the wall and everything around it — trees, street lamps and even parked cars — before he begins planning the mural. But delays in securing a wall meant doing things differently this time.

“This was not thought of to be the ideal wall for me," Twitchell says. "By the time the wall came about, I was already going to paint Rafer Johnson and Loretta Claiborne, and that’s two people, and here we have a wall 120 feet wide-by-30 feet high. But that’s great with me because I love having a lot of negative space. It just gives so much more power to the figures."

After he’s photographed his subjects and added their portraits to his sketches of the wall, Twitchell is ready to start painting. He paints small sections of the mural on polytab, a cloth-like fabric that can be adhered to most walls. Twitchell works in his studio with the help of a few assistants. Once they’re done, the mural can be installed in just a day or two.

“On installation day, usually we take all of the separate grids and line them up just to make sure they all fit together properly," says Marie Rooney-Hardwick, Twitchell’s assistant. "We do some alterations, a little painting. Apart from that, the rest of the work is just applying it straight to the wall.”

(Twitchell beside his mural halfway through the installation process. Photo Credit: Larry Hirshowitz)

Twitchell says he gives his “giants” neutral expressions, so that interpretation is left to the viewer. His newest portraits are no exception. Clad in red and blue athletic warm-up suits, they stare down at the street from about 30 feet high on a wall at 1147 South Hope Street in Downtown L.A. He says they're part of an ongoing series called, "Monuments to American Cultural Heroes."

“I grew up in the '40s and '50s where it was very common to have sports heroes, movie heroes," Twitchell says. I think it was a good way to grow up because you tried to be the best you could to be more like your hero. I think heroes are really important and I think America is the less for not having more heroes. These are two true, walking-around, legendary people that deserve everything they’re getting.”

Note: The Twitchell mural is one of three commissioned by Toyota that are located near venues hosting the Special Olympics World Games events. Below is information on the other two murals created by L.A. artists.

David Flores created a mural called World Stage Legacy which is located at the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum. The mural includes Special Olympics athlete and World Games Global Messenger, Ramon Hooper alongside iconic figures with a connection to the Coliseum.

The artist Cryptik created a mural located at 1248 South Figueroa in Los Angeles. It's called The Greatest and features a large-scale portrait of Muhammad Ali.

How a Matthew Sweet album inspired the stage musical, 'Girlfriend'

Can you remember what your favorite album was when you were in middle school? Sometimes that music, embarrassing as it might be, sticks with people for life. And in the case of playwright and lyricist Todd Almond, that album is Matthew Sweet's 1991 record, "Girlfriend."

So when Almond began work on a musical based on his experiences as a gay teenager growing up in Nebraska, it only made sense for Sweet's album to be involved in some way. What ended up happening, however, is that the album "Girlfriend" ended up forming the entirety of the lyrics and music for the show.

When Almond joined us on The Frame, he talked about the loneliness he experienced growing up in Nebraska, how he navigated his awkward teenage years, and the new play he's doing with Courtney Love.

Interview Highlights:

So what was it about this album that affected you so greatly?

There's a small group of us that have this reaction to that album where it just moved us profoundly. I think that there's an operatic-ness about love within that album, and maybe I was just feeling so alone in Nebraska and I wanted so desperately to be in love like the people around me that I saw having this experience. I think that's partly why I'm in theater and why I'm a writer — I was able to internalize all of that angst and all of that frustration and I had to live with it for a long time.

I want to talk a little bit more about that, about the idea of being isolated and growing up in Nebraska as a gay teen. We talked five years ago when the show premiered at the Berkeley Repertory Theater, and here's something you said to me: "There were no Internet chat rooms, no gay celebrities who were out. I look back on that time in my life and my heart was always heartbroken."

[laughs] I wish I could say I feel differently, but that's really true. I think part of the human condition is isolation in one way or another, and I think in that particular time for a gay teen in the Midwest, the isolation was pretty acute.

There was no representation on television and there was no Internet, so you weren't able to log on and see other people like [yourself] at all, and there weren't cellphones, so you couldn't communicate in that way.

I honestly felt like I was the only gay kid in my town — which wasn't true, I now know — and I thought that I was probably the only gay kid in my state, which of course is not true. But that sensation was pretty potent at that time. In retrospect, it was a beautiful breeding ground for art, but also for desperation. [laughs]

Even though this play isn't autobiographical, it's based largely on some of the emotional experiences you went through at the time, and it's also important that Matthew Sweet's record was a rescue for you in some ways. So how did those two things, your experiences growing up as a gay teen in Nebraska and Matthew Sweet's album, coalesce into this show?

There's a moment in the piece when the two boys are driving in a car, and one has given the other a tape of the album and he asks, "Did you listen to it?" The other one says yes, and he says, "I love music a lot. It's the only thing that keeps me from..." — and he doesn't finish the sentence. I feel like that kind of answers the question that you're asking.

I remember making a mixtape for a certain boy who was straight as could be, very nice, and I put all of these songs on the tape and thought, I hope he hears what I want him to hear. Later, when I thought back about wanting to write something about that time in life — which I think everyone goes through, gay or straight — the horror of not knowing what to say to somebody, [wondering] do they feel the same way you do, and how will they react if you say it out loud ... that album automatically starts playing in my head when I think about that time.

It took me a long time to figure out that these boys can use those songs to communicate with each other, so it's perhaps interesting for two boys to be sitting in a car, singing a song with the lines, "I'd sure love to call you my girlfriend," and hope that the other one is understanding that they actually mean that. But you have plausible deniability: it's just a song on the radio and I'm just singing it, so I don't actually mean what you think I mean, but I really do. [laughs]

I want to talk about one of your most recent shows, called "Kansas City Choir Boy," which debuted at a small theater in New York earlier this year. You not only wrote it, you performed it opposite Courtney Love. How did that collaboration come about, and what's next for that show?

My husband is an agent and he has been working with Courtney for the last couple of years, so I got to know her personally. And for whatever reason we really hit it off and we just have this great friendship. I wrote this piece called "Kansas City Choir Boy," and the Prototype Opera Festival in New York wanted us to do the show.

We had a wonderful Australian actress named Meow Meow who was originally going to do the part, but scheduling didn't work out so I asked, "Well, who can play this part?" You have to look at this character, and the only requirement is that, the second you look at them, you know they're destined for something that none of the rest of us will ever be destined for. They need to wear their destiny on the outside.

And [my husband] said, "What about Courtney?" And I said, "Well, obviously, Courtney Love is the perfect person for this part, but would she want to do a tiny, weird performance in a basement with 80 seats?" I asked Courtney and we had this long conversation about it, and she was like, "Let's do it."

She was flawless in the show, worked so hard, and is really great. We're doing it in L.A. at the Kirk Douglas in October. It's a string quartet, a chorus of six girls, me, Courtney, techno beats, a weird piano that I play ... it's wild.