Singer/songwriter Perla Batalla and playwright Oliver Mayer are collaborating on a new project about the iconic Mexican artist; California Light and Space artist Robert Irwin debuts a new work in West Texas; artists are going public with work at the Republican National Convention.

Artist Robert Irwin checks out the light in West Texas

With construction staff all around, Robert Irwin stands in the middle of a work-in-progress. In fact, it’s been 17 years in progress. The West Coast artist is finalizing a permanent installation for the Chinati Foundation.

Chinati, that mecca of minimalism, was launched by the late artist Donald Judd in the tiny West Texas town of Marfa. And this summer, Irwin is about to be canonized in that small circle of artists who include Judd, Dan Flavin, Carl Andre and John Wesley. There's two wings of his art installation – a stark grey building around a central courtyard. Inside, long banks of high windows filter in the desert daylight in astonishing ways.

As Irwin walks around the site, he meticulously checks if things are in order, and starts to adjust a filter on the windows.

IRWIN: You’ll notice this building is split in half. It’s a real subtle thing, but the building is two buildings. One’s a dark building. And one’s a light building. So right now I’m playing with the quality of the light.

At this point, Irwin is still making changes on-site. But he doesn’t want to overdo it.

IRWIN: Now comes those crucial [questions]: When does it become too much? Oh gosh, isn’t that an interesting idea?

These changes can be nerve-wracking, says Jenny Moore. She’s the director of the Chinati Foundation, which has already raised $5 million for the project — and changes cost money.

MOORE: Watching him make decisions on a construction site — that feels like watching an artist work in their studio. I mean, this is his studio. It’s a little bit startling at first to see him moving things around, at the level of a construction site. Whether it’s moving a wall 10 feet or tweaking the height of a window or something like that.

She’s confident in Irwin’s judgment and walks out to see his sculpture in the courtyard.

"Oh my God, I've walked this site so many times," Moore says. "To see it fully manifesting, it’s just... God, it just gets me every time. It really does."

Outside, Irwin has arranged a basalt rock column, raised Corten steel planters and Palo Verde trees, planted in rows.

MOORE: I think what we’re sitting in right now is a central part of the art itself. We’re sitting in a courtyard. And Bob has worked at gardens and exterior spaces for several decades: the Central Garden at the Getty; the master plan, including all the exterior spaces, at Dia:Beacon; the palm garden at LACMA. And he’s now in talks right now about the master plan at LACMA and its expansion. But already I think you can feel a heightened sense of space here in the courtyard.

Back inside, Marianne Stockebrand, the first director of the Chinati Foundation, watches Irwin perfecting his windows. "You know, he knows he always keeps a certain freedom for making changes up to a certain scope," Stockebrand says. "I mean, he wouldn’t start all over." (laughs)

Irwin considers the trees he just planted. Palo Verdes are found in Southern California, but here in West Texas, they’re on the edge of their frost tolerance.

IRWIN: When you look at the courtyard — the addition of the trees, which we just now put the first row. Whoosh! You know — dynamite! It really worked. So now I know I really want the second row of trees.

Irwin laughs when asked if he’d remove the trees if they didn’t work. “In an instant,” he says. This doesn’t surprise art critic Lawrence Weschler, who watched Irwin make delicate changes while building the Getty Gardens in L.A. in the 1990s.

WESCHLER: At the Getty, he had literally hundreds, probably thousands, of stones that he was moving around. Something you would barely notice, but it’s exactly the kind of thing he works on. And in that case, he was working with huge earth-movers to move boulders two inches to the side, and so forth.

Weschler was working at UCLA in the ‘70s when he first met the artist and was fascinated with Irwin’s focus on presence over image. "He happened to live in Westwood," says Weschler, "and we basically had lunch together for the next three or four years." Those three or four years of lunches turned into three or four decades of conversations. And they were compiled in a book by Weschler called, “Seeing is Forgetting the Name of the Thing One Sees.”

WESCHLER: Setting the Getty aside, he has had sensational, amazing shows over the years at different places. None of which still exist. He does now allow them to be photographed. But, none of the work, the major installations, and so forth, still exist. And this is going to be one of the unique cases.

Irwin installation at the Chinati Foundation in West Texas is the only freestanding structure devoted exclusively to his art. The artist knows he’s onto something big.

REPORTER: What’s that one feeling you get when you’re in this space?

IRWIN: Aw, well, I’m not going tell you. I’m going to let you figure it out. So far it’s going pretty good. I think I got a winner on my hands.

And with that, Robert Irwin gets back to the job at hand – creating a permanent work of art.

Robert Irwin's installation at The Chinati Foundation in Marfa, Texas opens on July 23.

Art, politics and the Republican National Convention

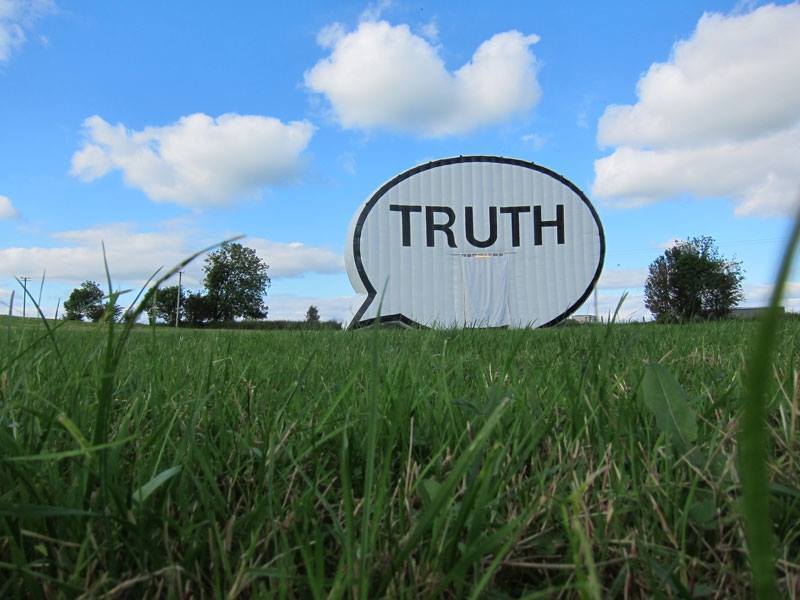

What is truth? This question will be discussed around the Republican National Convention in Cleveland this week. And we're not talking about Hillary's emails. This is a philosophical, question posed not by speakers or conventioneers inside Quicken Loans Arena, but by an art project called "The Truth Booth" that's installed nearby. And it's just one of a number of art works with political messages that are on display around Cleveland, timed to coincide with the RNC.

Randy Kennedy is an art writer for the New York Times who chronicled what types of political art are going to be displayed around the RNC this week. He laid out a few highlights for The Frame's Oscar Garza.

"The Truth Booth"

Hank Willis Thomas and some other artists have made this work that has been on the road for years now. It's this inflatable booth that looks like a cartoon word bubble that says "Truth" on in it, which is an extraordinary loaded term even before this campaign. The way it works is they invite people in and they videotape them completing the sentence, "The truth is..."

They took it to Afghanistan, they've had it in Europe, and they've taken it around the United States and recorded more than 6,000 responses to that. I think it's trying to show the complexity of what that means and it's trying to get people to talk.

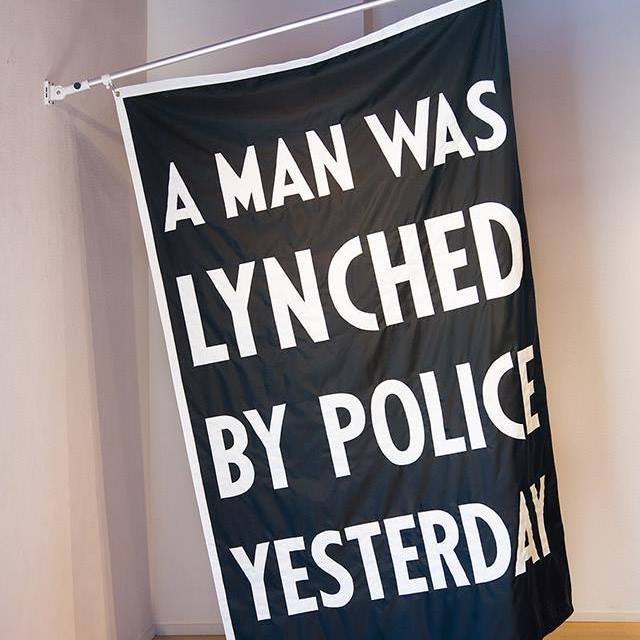

"A Man Was Lynched By Police Yesterday"

Hank Willis Thomas and an artist named Eric Gottesman, they legally formed a super PAC. The idea was to recruit artists and ask them to make new work or submit old work that is about political discourse and where we are now. Some of them are very open-ended and suggestive, some are very pointed one way or another, but a lot of them are thought-provoking.

[Dread Scott's "The Flag"] is one work in that project that is extraordinarily pointed and it's making a point about the police. It's an update on a 1930s NAACP flag. It's a black flag with capital letters on it that say, "A Man Was Lynched Yesterday," and this updates that with "A Man Was Lynched By Police Yesterday."

The artist knows it's a provocation and it's been flown as all of these tragic events have transpired around the country with police violence and violence against police.

"The American Dream Project"

Artists Nora Ligorano and Marshall Reese have taken these large word-based ice sculptures to previous presidential nominating conventions and also climate change events, and they essentially take words that have become cliché — or have become so much a part of political discourse — that they have very little meaning anymore.

The work that they'll be making and putting outside and allowing to slowly melt as a kind of performance this week in Cleveland is "The American Dream." You can look at those as a hit-you-over-the-head [message]: The American Dream is melting down, but I think it's a more complicated thing that they're up to about having people around watching this thing.

In a way, it's sort of entertaining. You're watching these words melt, which one is going to fall first, what's it going to look like? But these phrases are often: "The Middle Class," "The Economy," "The American Dream," "The Future" — these kind of abstractions that facilitate conversations.

"The American Dream Project Cleveland" will be live streamed here beginning at 12:30 p.m. ET on July 19.

'Blue House': A musical that embraces Frida Kahlo's 'female power'

In 1983, the writer Hayden Herrera published a biography of the Mexican artist Frida Kahlo. The book brought Kahlo out from the shadows of her larger-than-life husband, artist Diego Rivera.

The book also established Kahlo as a huge talent in her own right, and she was transformed into a feminist icon, spawning a cottage industry of books, documentaries, a feature film — and t-shirts and tchotchkes of all sorts that bear her image.

There also have been several stage productions about Kahlo, but the singer/songwriter Perla Batalla and playwright Oliver Mayer — both of whom live and work in Southern California — believe there is more to say about the artist, who died in 1954 at the age of 47.

Batalla and Mayer are collaborating on a play with music called “Blue House” — that’s a reference to Casa Azul — the Mexico City house where Kahlo was born and died, and in-between lived with Rivera.

The project has its roots in a 2012 exhibition of surrealist art by Mexican women at the L.A. County Museum of Art. For a performance accompanying the show, Batalla was among the musicians who were invited to select an artist from the exhibit and write a song inspired by her work. Batalla and Mayer spoke with The Frame's senior producer, Oscar Garza.

Interview Highlights:

Given her prominence in pop culture, why did you end up choosing Frida as your subject?

Batalla: We were trying to figure out which artist we would choose and Frida was the one I was trying to avoid because I felt like everyone would choose her. But as I learnined more about Frida, it [was] a no-brainer for me. I mean, she's German-Mexican; I'm German-Mexican. Her sense of art is that, as Mexicans, we see the world in a surrealist way. There is no "surrealism," it's just the way we see the world.

So that was the genesis of the play? The commission for one song?

Batalla: Yes. Then David [Batteau] and I started doing research and reading as much as we could and we said, This is not just a song. This is a musical. There's a great story here that needs to be told.

Oliver, were you daunted at all by the fact that this is somebody who's very well known and whose life has been examined thoroughly?

Mayer: Sure, there was hesitation. I figured that they got a lot of that information out there that maybe I could actually skip past. And that I could help Perla find the soul of the woman, in particular, and the man she loved and what it might be like to live in that house. The Casa Azul is a place I've never been to, but I feel like I've been there through the songs. Perla's been there. I've been in homes like that because I've been in homes with people who love each other and maybe have done each other wrong. There's something about the history and the ghosts of a place like that that I felt I could write.

But I'll tell you about this show and particularly this Frida — our Frida. I was very moved by a mashup I saw online — a photographic mashup. It was an image of Frida with the body of [poet-singer] Patti Smith. And it reminded me about her contemporary power, her female power: iconic, in your face, devil-may-care, sexual. Really interesting. And it gave me insight on Frida that I thought, I could do this. I'm hoping to be able to give that to Perla's and David's songs and to an audience so that we see someone who's really current, even possibly in the last days of her life. And even possibly at a moment where most of us wouldn't even be able to speak with the pain that she's feeling that she can still crack wise with a bottle of mezcal and a cigar and a lot of cursing, and really tell the world and tell her husband how she feels.

Perla, you've written the songs with your songwriting partner David Batteau? What was your approach going into the music? How direct did you want to be?

Batalla: Well, there really is no approach to how we do it. It's strictly the research. We start with research, reading everything we can get our hands on. I even started to paint and do art pieces. Through the research, things just pop out at us.

All three of us grew up in Mexican American households. I really had no knowledge of her until the '80s when Hayden Herrera's biography of Kahlo came out.

Batalla: We didn't either.

Then she became this icon of Chicano/Mexican-American culture here that has gone wavered a little bit, but she remains a presence. She's made that foothold here. Is that the same for you? Were you aware of her growing up?

Batalla: I think for Mexican-American women, especially, it was very eye opening to have a figurehead like Frida. All of a sudden, here's an extremely strong woman who does what she wants, says what she wants and paint what she wants. Discovering her was very powerful for me and many of my friends — not just Hispanics, but certainly for our culture, it was extremely important to have her and still is for a lot of women.

Mayer: My father was an artist so I was aware of Rivera at a very early age. I think it's a testament to how we've grown as a people, how we've grown as Americans, but maybe how the entire world's become more aware that it's not always about men. Even in Diego's own household. I think Frida had to remind him of that because he was a gigantic personage and in a lot of ways deserved all the attention he got. But he said something really powerful that I'm always reminded of in the play: he thought that her art was greater than his. And I don't think he said that in a passing way. I think he knew that she was really up to something really important, and not just for women.

This was a difficult and complicated relationship between Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo. How much of that did you want to get at in terms of the tension between them? How integral is that to the story?

Mayer: The play that we're working on now has everything to do with that battle and that love story, because I think all of the blows that each of them give in the play, and have given before the play begins, are in that house. That's why I think the title is right. I think it's probably the way a lot of us feel when we go home. We remember all the things that have happened there. Sometimes we can't forget even if we'd like to. But in their case, they were unable to part. Even when they divorced, they got married a second time.

Batalla: I also think that if you just talk about a relationship, having grown up Mexican and German, both of which are kind of strong, scary cultures ... when you get two people that have very strong opinions and have these personalities that cannot be denied, I'm sorry — there are just going to be fireworks. One thing I wanted to really express to Oliver was my need to always have that love there. She wasn't there as some victim. A lot of people [say], Oh, poor Frida. Diego was such an animal. She wanted to be there and she adored that man. I have no doubt in my mind that she adored him.

Maybe that bond in the music is perhaps best expressed in the song, "Tell Me You Don't Love Me Anymore"?

Batalla: Exactly. And "Tell Me You Don't Love Me" isn't like, Boo-hoo — tell me you don't love me so I can go die somewhere. It's, I dare you to tell me that you don't love me.

"The Blue House" will be presented Aug. 11 as a work-in-progress at the Ojai Playwrights Conference.