From The Frame's vaults: actress and writer Zoe Kazan was speaking about rampant sexual harassment in Hollywood months before the Harvey Weinstein floodgates broke; singer and performer Lizzo on her wild year that started with a fateful appearance on Samantha Bee's show.

Sexual harassment on set is ‘the status quo,’ says Zoe Kazan

Zoe Kazan is not afraid to address the political with the personal, as an actress and a writer.

This year she stars in “The Big Sick” opposite Kumail Nanjiani, playing his real life wife Emily V. Gordon. Their cross-cultural love story seems particularly poignant at a time when fear of "the other" can drive people to the extreme. And Kazan addresses the fragility of the environment in her stage play “After The Blast,” which just closed at Lincoln Center. In the story, the planet’s few survivors have been forced to live underground.

Zoe Kazan has worked in the entertainment business for a decade now, but with her parents being filmmakers, she’s been adjacent to the industry her entire life. Her dad, Nicholas Kazan, wrote “Frances.” And her mother, Robin Swicord got an Oscar nomination for writing “The Curious Case of Benjamin Button.” Together they adapted the Roald Dahl book, “Matilda.” Zoe's grandfather, Elia Kazan, was also an actor and filmmaker. And her life partner is the actor Paul Dano. Naturally, Zoe Kazan has a unique vantage point on Hollywood now and in the past.

In her conversation with The Frame's John Horn, Kazan opened up about the big topic of the day — the pervasiveness of sexual harassment and abuse in Hollywood and beyond. To hear the complete conversation, click the play button at the top of this page or get The Frame podcast via Apple Podcasts. Below are some of the highlights.

Interview Highlights:

On the long history of sexual harassment in Hollywood:

The history of our industry is a history in which women have been sexually harassed, raped, coerced, treated like objects ... treated as if we're not perennials — treated as if every season they need to plant a new crop of bulbs. Those bulbs are women and once you cut those flowers, there's no more use for the plant. Even the fact that we have a concept of a casting couch that people use colloquially is meaningful. The sexual harassment that I had described in experiencing in [The Guardian] is the tip of the iceberg in terms of what I've experienced.

I just did this wonderful project in Nebraska and I have a close girlfriend who's also an actress call me while I was there and say, Who is weird on set? Who are you having to avoid? She meant who's sexually harassing you. I said, No one. I'm having the cleanest experience. It's so remarkable. But the fact that's a question we call each other and ask ...

On everyday instances of harassment:

Someone was asking me, Have you ever experienced someone touching you in inappropriate ways? And I [said], If I started counting the number of times that a man on a movie set put a hand on the small of my back to guide me to set ... which he never would do to a male actor — I can't even count those times. I will say it's not across-the-board. I've worked with unbelievably respectful and professional men. Some of the greatest mentors in my life have been men. I feel unbelievably grateful to them. I don't mean to throw every single person under the bus. But it's the status quo.

On her interview with The Guardian and the risks of speaking out about harassment in the industry:

I felt very vulnerable giving that interview. When [the writer] asked me about sexual harassment, I was very careful about what I said, partially because there's a way in which women, when they speak out, [are] turned into targets. I didn't want to do that to myself. In some ways, I still don't. I still am not willing to say the names of the people I think have been most egregious to me, partially because I just don't want to bring their denial down on me.

On her dissatisfaction with Netflix and other studios who knowingly hired alleged sexual predators:

When these allegations started coming out against Harvey Weinstein, who I have no personal experience with ... everyone had heard. I have to say, everyone knows. Louis C.K., Kevin Spacey — these are names that, for years, we've heard whispers and stories. You want to look away with some of them. I certainly did with Louis C.K. But you hear them. When I hear Netflix say, We're not going to be in business with Kevin Spacey anymore. I love Netflix. I watch them almost daily. It really ruffles my feathers because I think, if you didn't want to be in business with a sexual predator then you should have never hired him in the first place. The thing that has changed is that suddenly it has become verboten to be in business with people who are being accused of sexual predatory behavior. That's the only thing that's changed. I'm not saying they should keep working with these people, I just find the sanctimoniousness with which they're washing their hands of this situation very hypocritical.

On the pervasiveness of the problem:

I had a lot of fear when these allegations came out against Harvey Weinstein, that people were going to treat him like the exception rather than the apotheosis of the problem. These women who've come out — women and men who've come out since then about other people — are real heroes because they are making it impossible for us to say it is just Harvey Weinstein.

On blaming agents and managers for enabling a culture where sexual harassment and abuse can take place:

I wouldn't point a very strong finger at the agents and managers to be totally honest because — maybe I should — it's the whole system. There's a whole system that allowed Harvey Weinstein to do this for 20-plus years. Yes, some of it is agents and managers, but it's also money people, PR agents and the paying public. We live in a patriarchy. It's not just in the film industry that sexual harassment occurs regularly. The whole world is set up in a way where women are not protected, where we are disbelieved. The fact that there are so many rape kits that have gone untested, for instance, is in a very casual way the most literal example of people turning a blind eye ... To point a finger at any one person and say, Oh that manager sent that woman to that meeting — you might as well point a finger at every single one of us.

On her steps for bringing about change:

I think one of the defense mechanisms that I have developed — sexual harassment starts really young, right? I remember being very small and adult men treating me in an inappropriate way. Especially thinking about, as I started to go through puberty, fathers of friends that I went to school with hitting on me at parties, not realizing that I was the same child they had coached on swim team four years beforehand. It's a very complicated thing.

I do think that I have developed, in response to it, a kind of gameness. Like, I'm going to laugh at your joke. And there's a way in which you learn [if] they put their arm around you, you slap their wrist in a flirty way and move away because you don't want to get in more trouble. There's a way that I have used tactics like that to get through uncomfortable situations. I don't think I can explain to men that you could be raped at any moment. I really can't explain what it feels like to know that you are physically small, that men are historically dangerous to women and to feel that you want to get through the world safely. So I think immediately about my own behavior, which is probably another way of victim shaming, to be totally honest. I think maybe the next time I don't reprimand in a kind and flirtatious way, maybe next time I reprimand in a real way.

Honestly I think that it's largely on the men in our industry and, frankly, in our world, to start examining their own behavior, talking to each other about what's acceptable and what's not. You know, I don't think it should all be on women.

To hear this entire conversation, click the play button at the top of this page. To get more content like this, subscribe to The Frame podcast on apple podcasts, Spotify or wherever you get your podcasts.

Lizzo wants to 'make the world a little bit better' with her music

The singer-songwriter known as Lizzo is getting ready to take her pro-woman, body-confident empowerment music on the road, which includes a Nov. 8 show in Los Angeles at the Fonda Theater.

She performs with a core girl group that includes her DJ, Sophia Eris, and two dancers who she calls "the big girls." Sporting unitards, they do coordinated choreography behind Lizzo while she belts out her music, dressed in a stylish leotard, no less.

Her song "Good as Hell," which appeared in the film, "Barbershop: The Next Cut," was a big hit last year. Samantha Bee invited her to perform it on "Full Frontal" the night after the 2016 election. She opened her performance with a rendition of "Lift Every Voice and Sing," also known as the "Black National Anthem."

Though the song was a last-minute addition to her performance, Lizzo says she'd been thinking about singing it for awhile:

I have been thinking about "Lift Every Voice" for a while. My old manager asked me months earlier, Would you ever sing the national anthem at a football game or ... a basketball game? And I told him, Yeah, I'll sing the national anthem, but I'm going to sing the "Black National Anthem." And I said that initially not as a joke — everything I say kind of comes off like half-joke, half-dead serious. And I said that ever since and I've been thinking about it.

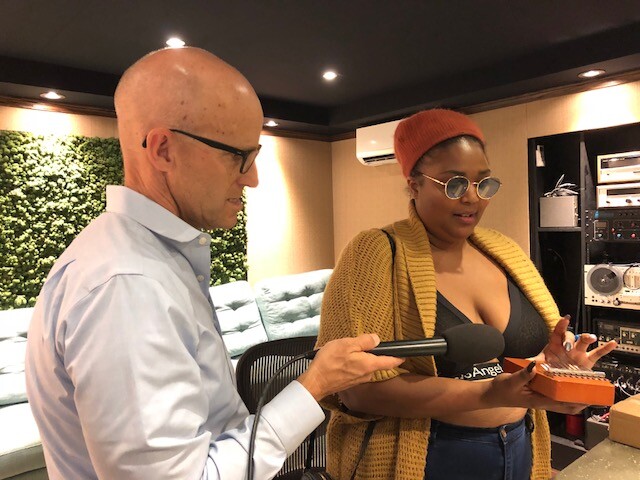

The Frame recently visited the recording studio where Lizzo makes her music, up a winding road not far from Dodgers Stadium. After showing us around the studios and the back garden, we settled in for a chat.

Click the play button at the top to hear the conversation. Below are some highlights.

INTERVIEW HIGHLIGHTS:

How do you cast dancers? Because your dancers don't look like people you see dancing in most shows. They look like ordinary folk.

Well, you know, everybody's ordinary to somebody. And I'd like to think that the big girls are pretty extraordinary. I think that they're more of a "spectacle" than the size two, super-buff dancer that you see. I want the women who dance on stage with me to be an extension of me, to be my dream. They dance like how I think I dance in my head. And I want them to be an example for anyone who doubts bigger women, who think that they can't be flexible, who think that they can't be spectacular and sharp.

I was thinking about this driving over here — that if someone were to watch your show and not hear anything, that what you were saying by who you are and the way you're performing on stage says as much about who you are and what you have to say as your lyrics do. Do you buy into that?

I think that's pretty cool. I With a lot of people who have an impact like that, it's never really intentional. Like, I didn't say, OK, being pants-less on stage is going to be this statement. I just don't like wearing pants on stage and I think I have really nice legs.

It's the era of the individual. I think that we've been kind of homogenized and put in boxes and socially taught that certain boxes are who we should be. I think the desire to be an individual is starting to flourish and I think that's why people catch on to me.

I want to ask you about something that happened almost exactly a year ago. You went on Samantha Bee's "Full Frontal." It was the night after the presidential election and you began your performance by singing "Lift Every Voice and Sing," which is also known as the "Black National Anthem." Was that something you planned to do? Why was that the right song at the time?

We had months and months and months of planning for that. The girls were wearing suits because we were going to have a whole montage of women in power suits and we had so much planned to celebrate women and the first female president, you know? We were on the plane flying to New York and I was watching the election on the back of someone's [seat] and I went to sleep and I woke up in New York in a Trump presidency.

And then Samantha came in my dressing room — she was crying, she was so devastated — and she said, What do you want to do? And I said, We're going to continue to do "Good as Hell" because, first-off, I have a job to do. And also part of that job is to uplift people. So when I thought of "Lift Every Voice," I asked her, Can I do anything? Can you see if [the rights are] clear? Can I sing this on television? And they just were like, We don't even care if you can't. And they did the research and said, You can. And then I was like, Okay, horns, just play this one note and I'll sing over that.

I realize there's two things you can [do]: watch history happen or choose to be a part of it. And instead of ignoring it, I chose to engage in it.

How much of your music and your art and everything you believe in is about empowering other people to live up to their potential and do what they can do to change the world? You're not telling them what to do, but you make them feel as if they have the opportunity to do that.

I think that's the reason why I am doing this. A couple years ago, I decided to dedicate myself to positive music because if I'm going to do this, I might as well make the world up a little bit better. But I never want to tell anyone what to do because I don't want anyone preaching to me. I'm not a preacher, I'm a musician and I'm a singer. So what I love is when people listen to my music they put on a Lizzo suit or a Lizzo mask or a Lizzo mindset or mind frame and they feel emboldened. But the reality is my music is what I'm going through and created to help myself.

I wrote "Good as Hell" a year ago to help me, now I'm performing it on stage. I'm so sad all day and then I get on stage because it's my job and as I'm singing "Good as Hell" sometimes, I'm just like, Oh, I wrote this for me! And I think that's super important. It's helped. I mean right now we're at two million views and I heard almost 10 million streams, which is massive for me. All those millions of people are being helped, but I wrote it for me.

I want to ask about your musical education, about the whole idea of growing up in a world in which Pentecostal gospel music was where your ears and eyes were opened — that there was a different way of using music to say something that was important.

I used music as a vessel into religion into Christianity. And then I used religion, the Pentecostal church, as a vessel into spirituality. And then I realized spirituality and music came back full circle. So I realized that music is transformative and all of my songs are a vehicle for change, for self-reflection, a vehicle for self-care, self-love. It's important and I think that it was instilled in me as a child. I continue to have little Eureka! moments when people tell me what my song has done for them. The last time I heard something that I was completely floored was last year in Austin when I play South-by-Southwest for NPR. Someone came up to me and told me that they were transitioning from male to female and when they listened to "Scuse Me," it helped them during their transition.

Because when I [sing], Look up in the mirror, oh my god it's me, she would look in the mirror during her transition and see this person and would be shocked at who she was becoming — sometimes excited, sometimes unsatisfied and wanting more. But mostly just appraising herself and praising herself. And that for me was, like, Yo, people are taking this music and traveling so far with it. They're flying with it and that's why I continue to do it.

To listen to John Horn's full interview with Lizzo, click on the player above.