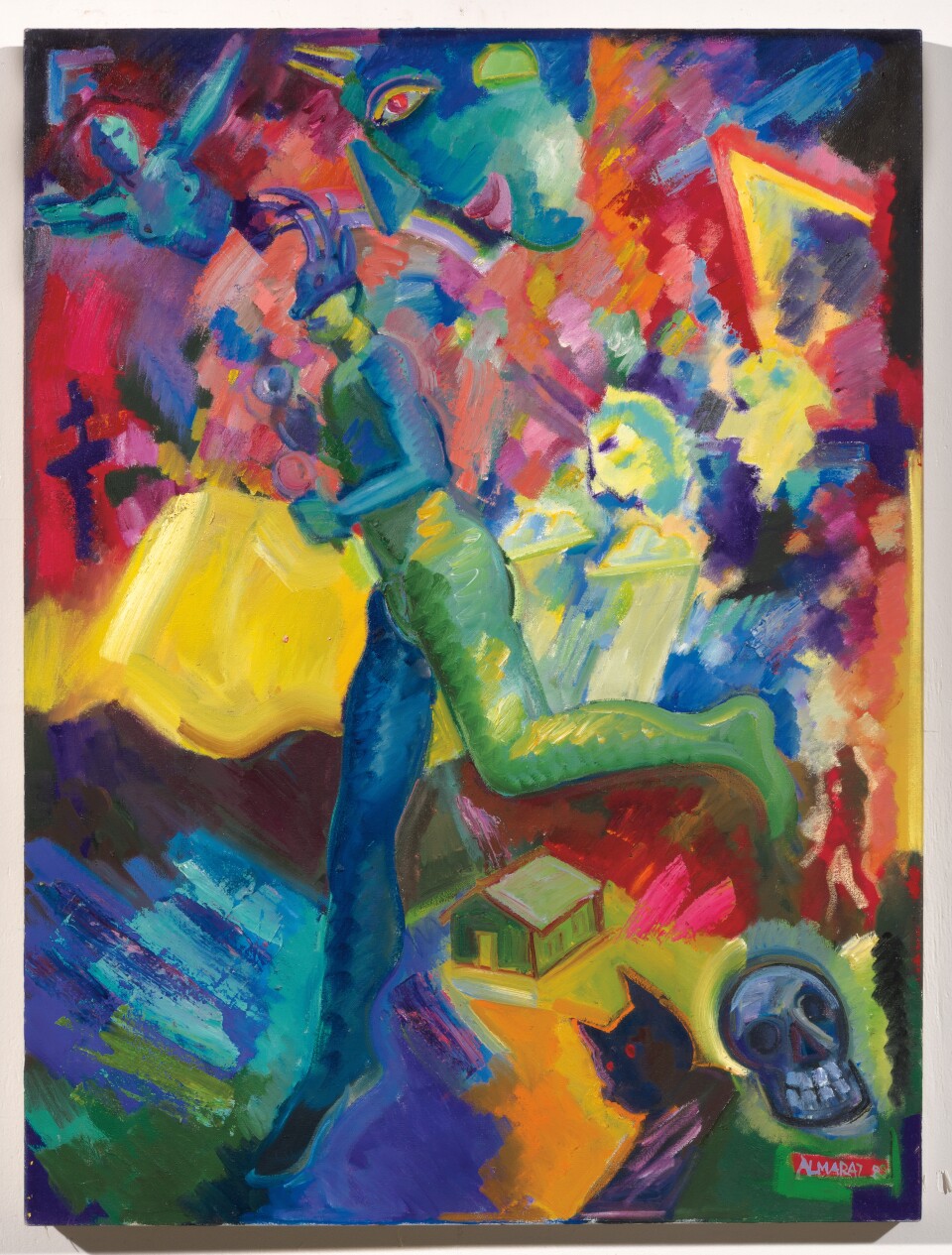

The late L.A. artist Carlos Almaráz is the subject of a new exhibition at the L.A. County Museum of Art; filmmaker Gregory Monro spotlights Jerry Lewis' directing career in "The Man Behind the Clown;" playwright Gretchen Law remembers comedian and activist Dick Gregory, the subject of her play, "Turn Me Loose."

Carlos Almaráz's art was steeped in the dualities of sexual and ethnic identity

Los Angeles has a rich history of contemporary visual art. Names like Ed Kienholz, John Baldessari, Bettye Saar and Ed Ruscha come to mind.

But the city’s Chicano art history deserves its own place in the story of L.A. art. Much of that work grew out of social causes — like the anti-war movement and the fight for farmworker rights.

In 1973, the artist collective Los Four was formed in L.A. The members were Frank Romero, Beto de la Rocha, Gilbert Luján and Carlos Almaráz. In 1974 their work was shown at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art — the first time Chicano artists were featured at a major museum.

Los Four eventually dissolved and Almaráz went on to make work that was less overtly political and more personal. By the time he died in 1989 from AIDS, his work was being acquired by private and corporate collectors. Now, his work is being featured at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art in a show that is part of Pacific Standard Time — the region-wide showcase of Latin American and Latino art in L.A.

Last week, The Frame's guest host, Steven Cuevas, visited LACMA to talk with the curator of the Almaráz show, Howard Fox, and also with theater artist and filmmaker Richard Montoya, who is making a documentary about the painter.

Interview Highlights:

On Almaráz living on the border of multiple identities: Mexican/American, bisexual:

FOX: One of his paintings, titled “Europe and the Jaguar,” I was really entranced by that because it showed a half-man half-jaguar — a symbol right out of Mesoamerican mythology — juxtaposed with a classical female nude, right out of European old master paintings. And between those two promenading figures, there’s this dapper young man, in a blue suit and a blue fedora. I realized, intuitively, that this was a self-portrait of the artist paying homage to the Mesoamerican mythology, modern and traditional European art. A lot of people thought you could not combine them successfully, that the juxtaposition would be too much of a clangorous rupture. But Almaráz embraced those traditions in a really interesting hybrid way.

On his role in Los Four, the Chicano art-collective:

MONTOYA: The idea of the collective was really in our hearts. We had our Che Guevara posters, Cuba, we talked Marx, we talked Mao. It was a movement that demanded to know how militant you were, how Chicano you were, how authentic you were. It wasn’t the place to explore one’s gender or spirituality. Carlos was one of the first, but not the only artist, to retreat from that — for much more personal and private work, exploring gender for example. That’s a heartbreak for a Chicano artist such as myself. But the good news for me, the thank you I feel I owe to Almaráz is that he leaves the movement, but that he leaves the art and the conversation in a better place than where he found it.

On whether Almaráz would embrace or resist the title of “Chicano artist”:

FOX: Carlos said, I’m an American artist [who] also happens to be a Chicano. So he acknowledges the heritage, he embraces it, but he does not typify himself, he does not specify or pigeonhole himself.

MONTOYA: I’ve never felt that Chicanismo was something that needed to be transcended. Or that we grow to a greater appreciation of art. For me, his genius is taking the best of all these things, and I felt that Howard [Fox] wasn’t taking any of that away. There’s a moment in the show, in a room that carefully looks at the gay aspect of Carlos’ life. That’s super important to so many of our transgender kids, our LGBT youngsters, our undocumented kids. He was an immigrant. Each one of those things has tremendous value. It’s not just that we’re in an “Oscars-So-White” town. The battle now moves into the large museums and into the theaters as well. We’re keeping it up because Carlos is kind of shoving open a door for us. And now that we’re in, with help of the curators and the third-tier allies, we’re in a tremendously exciting time. But there can be no let-up. We must continue to push forward.

'The Man Behind the Clown' shows Jerry Lewis as more than a comic

Most people know Jerry Lewis as a comedian and actor, but he was also accomplished behind the camera.

In the documentary, “The Man Behind The Clown,” French filmmaker Gregory Monro takes a look at Lewis’ struggle to be taken seriously as a director.

The film premiered at the 2016 Telluride Film Festival. The Frame host John Horn spoke with Monro then about why he chose to focus on this part of Lewis’ career.

INTERVIEW HIGHLIGHTS

On shifting the focus of his documentary:

I explained very quickly that I was focused on him as a filmmaker, rather than a comic. He is both, but I'm more interested in this because I think that, here in America, people don't have Jerry Lewis, the filmmaker, in mind. The author, the director, the producer, the technician — he was all that. So I was really focused on this immediately. I hadn't had to convince him, actually. He was okay with this. He's very grateful that someone could tell his story with that point-of-view, of him mainly having struggled with the fact that he became a filmmaker. That was also the beginning of his struggle in the United States.

On Lewis' quote, "The American critics are full of s---. They have no idea what I'm doing. They never have.":

He has always been, from my point of view and maybe his, misunderstood in the United States. More by the film critics, than the public. He had a tremendous success here at the box office. But as far as the critics, I think they didn't get the fact that Jerry Lewis becomes a filmmaker. He's not only a comic, he's all that. He's a complex artist, but he's a great artist.

On visiting Lewis at his home in Las Vegas:

I had no questions, I had only pictures to show him. So I brought pictures from France and I wanted him to react to the pictures. From there we could start our conversation. Of course, these are the pictures from a big part of his life. I showed him photos of his father, of Dean Martin. I like the pictures of Jerry Lewis with a camera, a 35-millimeter camera. I really like that one. I think he says, "That's the love of my life." He was in love with filmmaking. He was such a great technician; he knew everything on the craft.

On Lewis inventing the "video assist":

That's a monitor which allows you to [see] what you just shot [on film]. For a director and actor, it also allows him to watch what he is doing. Today, everybody uses that. But Jerry Lewis was the first to use this.

On Lewis' appearance in Martin Scorsese's "The King of Comedy":

He's not acting, actually, in that movie. Jerry always say he didn't do anything, he just said his lines and that's it. But the critics, they responded to that. Frank Krutnik, the film critic in the documentary, says it very well. He said, "The critics reacted as if they've never seen Jerry Lewis before." Meaning comedy is not sufficient, comedy is not serious. You're not a great actor when you're a comic. That's a pity because you are a great actor when you're a comic because it's a lot of work.