The filmmaker's new documentary is a look at how almost all aspects of our lives are somehow intertwined with the Internet; NBC's TV ratings for the Olympics are down, but online streaming is way up; indie director So Yong Kim's latest is "Lovesong."

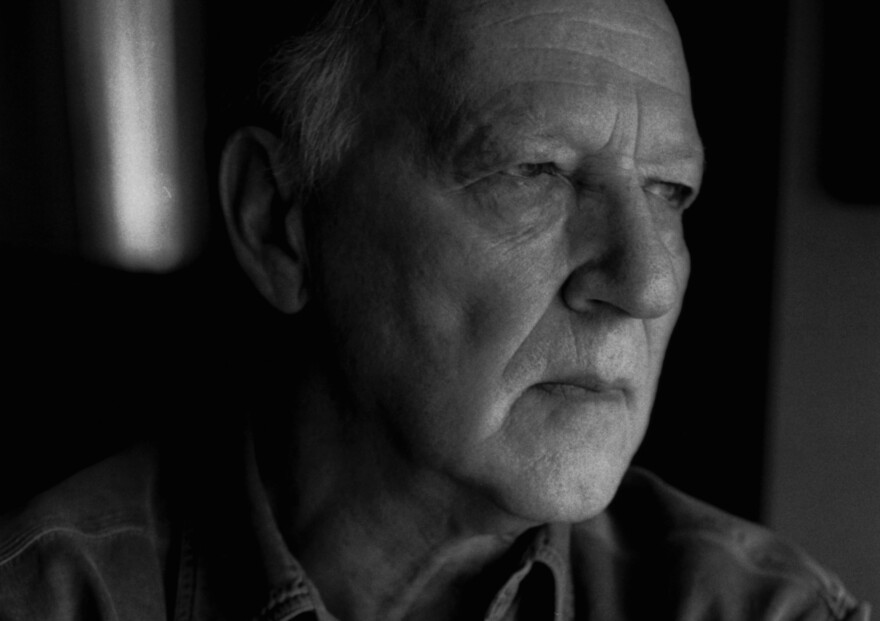

Werner Herzog takes on the internet: 'People do not read text in context anymore'

Filmmaker Werner Herzog’s new film, “Lo and Behold, Reveries of the Connected World,” is a contemplative look at how almost all aspects of our lives are somehow intertwined with that thing we once knew only as the World Wide Web.

In his 10 chapter project, Herzog traces the beginning of the internet and the first communication between computers at UCLA and Stanford universities, and asks scientists today to envision where the internet might take us in the future.

Ironically, Herzog is somewhat of a luddite when it comes to modern communications. He doesn’t own a cell phone, doesn’t use social media and only uses email when he has to. But his innate curiosity is infectious, and you can’t help but contemplate both the dangers and the wonders of our connected world along with him.

When he stopped by our studio recently, we asked him how he approached such a broad subject.

Interview Highlights:

What kind of research did you do before making "Lo and Behold"?

I didn't do any research. I came with a huge amount of curiosity and I came with a bucket list of things that fascinated me — artificial intelligence, video game addiction, tweeting thoughts. I mean, recording thoughts with a potential of tweeting them without a laptop in between.

Straight from your brain, more or less.

Straight from your brain, which is in a way possible. You can actually identify... you're sitting next to me and you're reading a book. With an MRI you could identify you are reading this book in Portuguese not in English because the grammatical structure of Portuguese somehow has it's own structure and it's own pattern. So there's a lot of types of events out there. Hacking, it's on and on and on. And I was totally fascinated by it, but I did not do any research.

We're speaking one day after a small electrical glitch grounded Delta's airplanes. Part of your story in the film is how perilous our dependence on technology is. And I suspect you would guess that these kinds of events are not rare occurrences, but they could continue to happen in greater magnitude?

Correct. What we overlook quite often is that the internet is very vulnerable. Vulnerable, let's say, in terms of hacking. Vulnerable in terms of, let's say, a solar flare which may wipe it out completely for a given amount of time. And then some computer glitches. What we should really reflect upon is disentangling some essential things from the internet. The crazy thing is that, for example, on the International Space Station, when I make a phone call from one end of the modules to the other — only something like 70 feet of distance — they call each other and it goes via internet.

It's routed back to the planet.

Yes. That's very strange and shouldn't be like that. And when the internet is down, you cannot even buy a hamburger anymore. You cannot flush your toilet anymore. No water would come from your faucet because the water supply is somehow organized through the internet. No phone calls, no communications, no radio, no government websites. You cannot renew your driver's license and you can't call the police. The police even wouldn't find you because they go on GPS. So it's a kind of an alarming scenario and we have to try to find ways to disentangle ourselves.

Given all that you've learned in making this film, outside of the use of technology, did it change the way that you look at the world? Do you have canned vegetables in your closet now in case the internet goes out? What did it do to change your way of living?

No, I don't have any survival supplies. And I don't have a cell phone. I'm not as vulnerable as others because I live a life that is, of course dependent on the internet in basic provisions like electricity and so on, but I'm not really, as a cultural being, connected to the internet.

What do you think are the dangers, as far as understanding the world and the way in which people get and filter and rank the quality of information that they're getting?

There's a problem. Deeper critical thinking probably comes by doing some real thinking and it comes through reading books not reading just tweets. Of course, for example, I run my own film school, a wild, guerrilla style film school called the Rogue Film School. I tell everyone who applies, you have to read. Read, read, read, read, read, read. If you do not read, you will probably become a filmmaker anyway, but a mediocre one at best. All the great filmmakers — look at Terrence Malick. He reads voraciously. Coppola reads. Errol Morris reads. Joshua Oppenheimer reads all the time. So the great ones all read.

But we're in the middle of an incredibly important election right now in the U.S. and people don't read. What does that do in terms of the quality of debate?

I do believe that there is an innate intelligence in the electorate. There's no innate intelligence, for example, in matters of the media. And I'm speaking...about tweets and things like that. I do believe that there's an intelligence that is beyond a collective intelligence, that is beyond the polls. This is why I believe the American voters will take a good look at the choices.

The internet, social media and streaming movies has been hugely important to your career. What are your feelings about how it has helped audiences discover and consume your work?

It's only very recent. My most recent film, a film on volcanoes, will go directly to Netflix. Of course what we are witnessing is a shift in distribution systems. The distribution system that we have so far for movies functions only basically through the big studios. The so-called arthouse films have vanished and the distribution systems for it have vanished. I never wanted to be arthouse films and I think I never was, but the system is somehow crumbling and new forms are emerging on the internet. I welcome it. I welcome it, although Netflix has disadvantages. You have films disappear like in a black hole. You're not sitting in a theater and you have the ripple effect from laughter coming from the first rows and rippling all the way to the last row behind you. You don't have that. You don't know how many people saw it, what age groups. It's not disclosed, I regret. One day I hope all these systems like Netflix, Amazon and whatever is out there will release figures and will release more details to the filmmakers to know what is the nature of my impact.

Identity theft is an illusion because the self does not exist.

— Werner Twertzog (@WernerTwertzog)

You mentioned earlier about the Werner Herzog imposters that are out there on social media. What are your thoughts about a guy like the English professor, William Pannapacker? He's created a Twitter account called @WernerTwertzog. He has more than 40k followers and he's tweeting fake Wernerisms, celebrating your birthday and things like that. Do you find that flattering, a little strange or both?

I must confess, I never heard of that one, but why not? If it's intelligent satire, it's fine. However, we have to be a little bit cautious on the internet. People do not read text in context anymore. They read it literally. I'll give you one example: there was a letter to my cleaning woman. Within less than a line, you could tell it was an outright satire. It was very nicely written and went viral and almost everyone believed that it was Werner Herzog, somehow in a diatribe against his cleaning woman. Only two hundred voices... noticed that the writer of this had outed himself. It says, 'Werner Herzog's letter to his cleaning woman' by Scott something. So it's right there. It's in front of your eyes but they cannot read context. They cannot understand that this is satire. It was actually good satire and I enjoyed it.

People watch any movie like this with certain biases. Some people look at this movie and feel that it's really optimistic. Some people look at it and feel pessimistic. Are you yourself optimistic about the internet and our future or are you worried about where it might all take us?

I would say, it's hard to speak about optimism or pessimism. It's the same thing like, are we optimistic because we have electricity? Or are we pessimistic? I would be pessimistic once they strap me on an electric chair. Then I would recalibrate my optimism about electricity. (Laughs) Is it going to fry me or not in seconds? But, I think the dangers we are encountering is not only based on the internet, we are just a little bit more — massively more — vulnerable.

But at the same time, what we have to look out for is how do we treat our planet. How do we organize our systems of connectivity and life together on this planet? I did some filming in Ethiopia for my volcano film and there are scientists who just excavated fossil remains of early Homo sapiens from about a hundred thousand years back. I asked one of them, do we have another hundred thousand years. They're very doubtful. What is interesting is that one of them explicitly speaks by looking at what is coming at us and how we are behaving. Within a thousand years from now, there will be a very critical phase and we better learn from our mistakes quickly.

'Lovesong': Another intimate film from director So Yong Kim

So Yong Kim is a director who’s known for making rather intimate and quiet indie films that focus on the human condition.

Such is the case for her latest film, which marks her fourth outing behind the camera. It’s called “Lovesong” and it’s about two friends whose relationship is transformed when they go on a road trip. The film recently made its L.A. debut at the Sundance Next Festival.

The Frame’s James Kim recently spoke with the director about how she got into filmmaking, her personal inspiration behind the movie, and why she's attracted to making intimate films.

INTERVIEW HIGHLIGHTS:

Getting into filmmaking:

I didn't really choose filmmaking as a career path, per se, I feel like it kind of chose me. My first degree was in business so I had to learn about money [laughs]. That was the requirement from my mom. She said that she would pay for my college education if I study business for four years, and she promised me that afterwards I could do whatever I wanted. So it was my ticket to freedom.

My partner, Brad [Rust Gray], was going to film school and was making his first feature. And I watched him and helped him on that film, "Salt," which was made in Iceland. I thought, I could do that, and I started to write and started to make films.

The real-life inspiration behind "Lovesong":

As I'm getting older you kind of reflect on some of the regrets you might have in your life. I also wanted to explore a love story, because to me, doing love stories are exciting and it's fun. It kind of renews your belief in life in a way.

To me, "Lovesong" is a fun story in a way. I think people might think, Wow, I wouldn't call "Lovesong" a fun, romantic story, but I wanted to go into relationships between friends: What is that boundary, and when does that get muddied, and how do you get through that so that you could still be friends? I think those kinds of boundaries are very difficult to navigate, especially when you're young.

I had a relationship in college with a best friend that was kind of muddy and [I] didn't know where it could go.

Bringing her personal life into filmmaking:

Filmmaking is also about learning about myself and trying to understand more deeply. I think that's just part of our existence.

I was born in South Korea and I grew up on a farm with our grandparents. I think just growing up with them in the fields and orchards made me very melancholic at an early age. But my family immigrated to Los Angeles when I was 11, so I'm also a product of Los Angeles. I feel like I'm trying to capture a certain element of that melancholia in my films.

I think intimacy is the key that I try to create between the viewer and my characters because I think that's the most important aspect of storytelling in film.