With "Logan Lucky," Soderbergh returns to the big screen with a new strategy for indie filmmaking; Disney decides to go its own way with plans to launch two streaming services; a new virtual reality experience puts you into flatline mode.

The macabre VR experience Angelenos are dying to try

While Virtual Reality has been "the next big thing" for a while now, not everyone is trying to crack the gamer market. In fact, one company has launched a new VR experience that veers towards the more spiritual side, simulating a so-called near-death experience (NDE). The Frame contributor Collin Friesen tried it out and lived to tell about it:

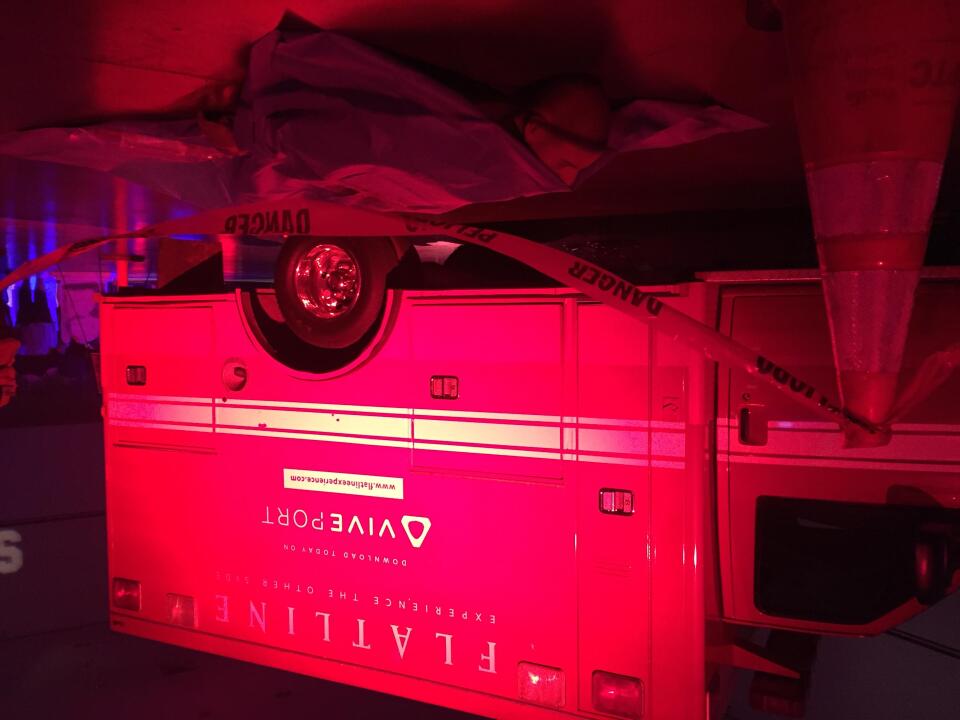

In the West Wing of the Los Angeles Convention Center recently, a massive line formed to step into the back of an ambulance for the “Flat Line” VR experience. It stretched well beyond the decorative corpse under the tarp and the decapitated clown tableau. The experience debuted at the recent Scare LA gathering – think Comic-Con, but for Halloween.

Once inside, co-creator Julian McCrea sat me on a gurney.

“We’re going to make sure the headset feels snug,” he tells me as he adjusts the goggles and headphones.

And like that, we’re off … I suddenly have the point-of-view of a woman who suffered a miscarriage and was basically left to die in a hospital bed. Not to be graphic, but when you look down there’s blood seeping through the blanket. And I’m hearing her tell her true story. Well, an actress telling me the story, as I’m sucked into a very realistic vortex. It has all the usual tropes of the near-death ride … a bright light, a feeling of calm, some scary bits — but more like just being shot down a cool tunnel.

That demo wraps up with a commentator of your choice. You can pick a doctor, scientist or a spiritualist, explaining their concept of what happens with a near-death experience. Either there’s a heaven or your brain is just messing with you. And that’s it. Six minutes later, Julian McCrea taps me on the shoulder and I’m back in the world of the living.

Now, it’s a little cheesy, with the waivers and the VR tech wearing medical scrubs, but the experience does stick with you. And the smell of the ambulance and the feeling of being locked in does a bit of a number on your rational brain. One of the first people in line was Fawn Quinn, who snuck over from another booth to give it a shot.

“I won’t lie. I had butterflies when I went in. I’m definitely glad I did,” she tells me after she climbs out of the rig.

The concept started 16 years ago when McCrea’s partner, John Schnitzer, heard a story from a friend about his near-death experience, and started to wonder how best to share it. McCrea says advances in virtual reality have finally made that possible:

“That story we are trying to tell about what happens to you, is better if it’s happening to you, or in first person, so that’s why narratively we went down that road.”

There’s no game here. You’re not killing aliens, or driving a Porsche through the Alps, or even trying to cheat death. This is a thinking – dare I say it – quasi-spiritual ride. And McCrea says they’re not only going for the young thrill seekers, but also that elusive NPR demographic, like the kind that listens to Krista Tippett’s high-minded show, "On Being."

"If you’re a thinker, a person who reflects," says McCrea, "you can come into 'Flatline' [thinking], I now know something more than I did. So I think that’s the right audience.”

Ted Dougherty is a VR director and theme attraction consultant. He liked the ride, but agreed that finding the audience will be the challenge:

“On the outside, it seems like it’s going to be macabre. At the end of the day it was an uplifting story, so I’m not sure this is the perfect thing for a Halloween type of situation. But these types of attractions can be monetized, so the possibilities are definitely there.”

This is only the pilot, but McCrea's company will be coming out with five other episodes, available for purchase on most gaming platforms. That will make it not only the first semi-serialized near-death VR experience, but the first time in history that Krista Tippett fans have been singled out as a gaming demographic.

To hear the story click the play button at the top of the page.

If 'Logan Lucky' succeeds, Steven Soderbergh just might upend the studio system as we know it

You might recall that Steven Soderbergh announced his retirement from filmmaking back in 2013, citing the “horrible treatment” of directors by the people who finance films.

After a stint directing all 20 episodes of “The Knick” on Cinemax, Soderbergh is back on the big screen with the film "Logan Lucky," out on Aug. 18. It’s a heist film set during a NASCAR race that stars Channing Tatum and Daniel Craig.

It’s the first feature to be released under Soderbergh’s company, Fingerprint Releasing, in collaboration with the distributor, Bleecker Street.

"Logan Lucky" is very much an experiment in a new way to finance, produce and distribute studio-level films without, well, a studio. (One note about Hollywood lingo that you’ll hear Soderbergh use: the phrase “P and A” refers to the cost of prints and advertising when releasing a film.)

When I met with Soderbergh recently in New York, I wanted to know what spurred him to take a break from filmmaking, and why "Logan Lucky" was his chance to step back in:

Interview highlights:

On pursuing television:

At the time I wasn't sure what my relationship to movies was, and also the business had stopped being fun — most of it. If one or both of those situations changed and my feelings shifted, I would step back in. It was never something I felt would be permanent.

As it turned out, I had a great time working in television and working on projects with other people. But in the fall of 2014, the "Logan Lucky" script came into my hands and it coincided with some conversations I'd been having both with Dan Fellman, who used to run distribution at Warner Brothers, and [the National Association of Theater Owners] — just sort of free form conversations about what was going on in the film business, in regards to distribution. It became clear to me that we were nearing a point where it was possible to take a movie, that for all intents and purposes is a studio film with movie stars in it, and wide release it without the studio, in a way that didn't really exist before. When the script came in, I started accelerating those conversations and saying, OK, I think I have a project. Can we talk seriously about what that would look like?

On the release model:

It's important we frame what our metric of success is because it's very different than what the studio metric for success is. What I'm hoping is that [through] Fingerprint, the company I formed to be the lead on this in conjunction with Bleecker Street and Amazon — who bought all the non-theatrical rights — that I can open up this path for a certain kind of filmmaker who wants to make a certain kind of film to reach a wide audience. There are plenty of good, small, independent distributors out there. This model is designed for wide release movies.

On this release model vs. a studio system:

I've had the luxury, since the beginning of my career, to be able to control the content of the films I've made. Even when I haven't contractually had those rights, I've been protected by producers. I've never had a battle about the cut of one of my own films. But I've had a lot of discussions and debates about how films are distributed and promoted. This is an opportunity to test a couple of theories and also to take advantage of some technology that didn't exist even four years ago, in terms of targeting people with specific types of advertising. When you spend a lot of money spraying out some advertising ... probably a significant percentage of the people that you're reaching really don't have any interest in your movie and never are going to. So, I've always wondered: Can't we figure out a way to stop reaching people who don't want to hear from us? And now with the sort of data-mining you can do, you can start to get more surgical.

On pre-selling the film, to avoid box office lulls:

This is a model that's been around for a long time ... this independent model of pre-selling to cover the negative, and in this case, selling the non-theatrical rights to cover the costs [of advertising and making prints]. The only thing at risk for any of us is the time it took to make the film because everybody worked for scale. But there's nothing to recoup, we're zeroed out when the movie opens.

On tracking the film's profits:

It's very transparent. The money goes right from the theaters into an account that everybody will have a log-in and a password. You can literally watch whatever money goes from the theaters into this account. It's completely clear and simple. That's the way I think it should work. Compared to most businesses of its size, Hollywood's actually remarkably transparent. And the amount of data that they turn over to the guilds every year is significant and very granular. The interesting thing about the guilds is, since the studios don't share information with each other, we get all the information from all the studios. We have a snapshot of the entire industry that even the studios don't have. So it's actually, I believe, a fairly straightforward, economic engine.