Filmmaker (and self-professed troublemaker) John Waters spits some wisdom about living life by your terms and offers his advice for young people in his new book, "Make Trouble," based on his 2015 commencement speech at Rhode Island School of Design; A look at the women of the real and the fictional 'Silicon Valley'; Summer blockbusters hitting theaters sooner and sooner and what actually defines a summer movie is rapidly changing.

Think there's a lack of women on HBO's 'Silicon Valley'? It's just reflecting real life

HBO's satire "Silicon Valley" has returned for its fourth season and, with it, the five guys who comprise the fictional tech start-up Pied Piper.

The two female venture capitalists are also back as regular characters, but aside from them, the presence of women is still pretty sparse. But how accurate is it to the real Silicon Valley that the show satirizes?

To find out how the gender politics in the HBO comedy compare to the real tech world and how they compare to Hollywood, The Frame contacted two women who are in a position to know a thing or two.

is the executive editor of Recode, host of the podcast "Recode Decode" and a consultant on the series.

is an actress who plays Laurie Bream, one of the venture capitalists on the show.

They spoke with the Frame's Darby Maloney about the women of the real and the fictional Silicon Valley and if women have it better in Hollywood.

To hear the story click the blue play button at the top of this page.

ON THE RATIO OF WOMEN TO MEN IN HBO's "SILICON VALLEY" VERSUS THE REAL TECH WORLD:

SUZANNE CRYER: They've taken a fair amount of heat for the amount of women on the show. But the reality is, with two women in series regular jobs on the show, they are already far outside of the norm of Silicon Valley.

KARA SWISHER: I've been covering Silicon Valley since the dawn of time. Since the early 90s. So I think it's perfect. I think they really do - you know what they do? It's sort of gentle mockery but it's based in fact. There's always sort of a smart woman around - and should be more smart women around, but there aren't as many because it's dominated by men.

ON THE CHARACTER OF VENTURE CAPITALIST LAURIE BREAM:

SC: Laurie Bream is different than most female characters that you'd see on TV because she's completely analytical. The way the character was written was very, very specific. And when I read it I thought, I'm not going to do my hair for this audition. I'm not going to wear makeup. I'm not going to wear clothes that show my body. And I am not going to make eye contact with anyone that I'm reading with, or the camera. Because I felt that she was a certain kind of person - and you can draw what ever conclusions you want about that. She doesn't like to be touched. She doesn't like to look at people. But I was scared because I thought, Well they're either going to hate this or it'll be what they're looking for.

It's extremely, extremely hard for a woman to go into an audition in Los Angeles and allow herself to not present herself in her best light. It's very hard to go in without makeup and hair. Even when you're playing a beaten-down housewife on CSI: Miami, you still use every hair piece in your bucket and 17 pairs of false eyelashes.

ON THE ACCURACY OF THE GENDER DYNAMICS IN “SILICON VALLEY”:

KS: The way male characters talk about women is dead on. They're a little bit objectifying them, at the same time they're sensitive to their objectifying language. So they're aware of what they're doing but it happens just the same anyway.

SC: Part of the way that [Laurie Bream] is the way she is on the show is that she's wired that way. And part of it is, she has created a protective wall around herself, to insulate herself from some of the inherent sexism that she knows she's going to meet. So I think some of it is calculated on her part.

KS: You know one person came up to me recently and said, How do you get more women in tech? I'm like, Hire them. How about that? It's something the community talks about and then does nothing about. So it, in a lot of ways I suppose it's better than most of the world, where they just ignore it completely. They give a lot of lip service to diversity and then when the numbers come out, they're exactly the same. Mostly white, mostly men.

ON WHETHER IT’S BETTER TO BE A WOMEN IN HOLLYWOOD OR SILICON VALLEY:

SC: It's much better for us in Hollywood than it is in Silicon Valley. I mean Silicon Valley is really - there's such a small percentage of women. When you look at a big action film - if you compare action films, they're like Silicon Valley, where there is one chick smiling and waving on the side while the men are driving the tanks down the road. But I do think that the level of scrutiny that you're subjected to is very similar. Female VCs and female founders of companies in Silicon Valley, they say a lot of times it's enough for a guy to be hip and daring to get himself funded. But women have to create a profit stream and have to create so much more of a projection of, like, a solid business. That's scrutiny and that lack of faith is certainly felt by all actresses. Most of women in Hollywood feel that they do need to present themselves to be sexually attractive all the time because god help you if you look over thirty.

"Silicon Valley" airs Sunday nights on HBO. To get more content like this, subscribe to The Frame podcast on iTunes.

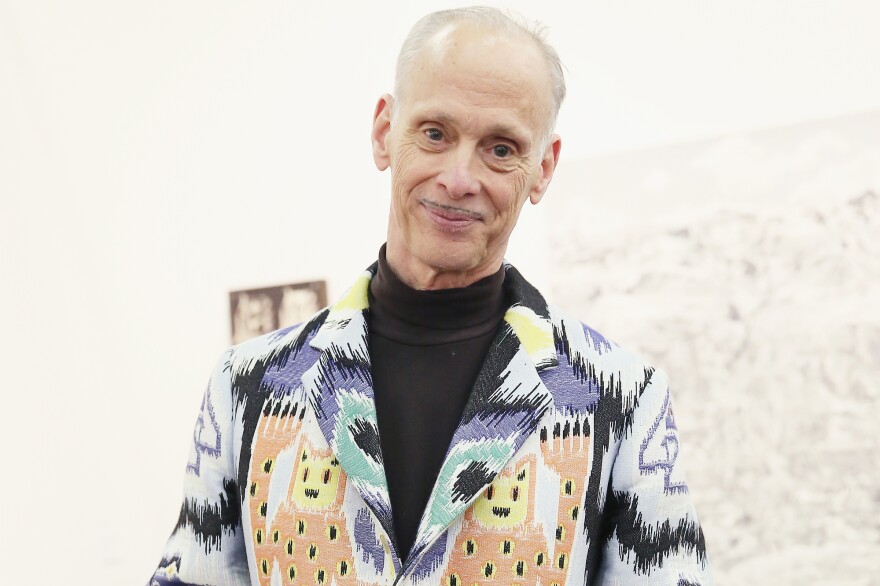

Filmmaker John Waters on 'Making Trouble,' the NEA, and bad reviews

Filmmaker John Waters has been called a lot of names in his long career — “The Prince of Puke,” “The People’s Pervert,” “The Pope of Trash" — and he’s embraced them all.

From his controversial early films like “Pink Flamingos” and “Desperate Living,” to more mainstream movies like “Hairspray” and “Crybaby,” Waters is known as a trouble-maker.

In a commencement address Waters gave in 2015 at the Rhode Island School of Design, his advice to the graduates was to go out into the world and make trouble from the inside:

from

on Vimeo.

That speech has been turned into a new illustrated book called "Make Trouble." Waters spoke about it with The Frame's John Horn.

Interview highlights:

On how his early education set him on a rebellious path:

My interests were discouraged in school. In sixth grade, I went to a very good private school, and I did learn there. I learned how to read and write. If I had quit school in sixth grade, I would know as much as I know today and would have made one more movie. By the time I got to college, I was so bored and angry. I did get thrown out for marijuana — one of the first busts ever. But it wasn't the college's fault. I don't think any college then would have let me make "Pink Flamingos." I think today they most certainly would. I think times have completely changed. There are schools for weird children now. There wasn't when I was young.

On getting interested in contemporary art:

My parents were very supportive, but my parents very much believed in good taste. So I learned those rules. And I always said, You can't break the rules if you don't know them. But I grew up in the '50s, and the '50s was a terrible time. I was rebelling from the conformity of everywhere. I didn't really think about things and was not interested in things that other people my age were. That didn't really bother me. I remember when I first went to the Baltimore Museum of Art and I bought this little Moreau print in the gift shop. I took it home, and I was like 12-years-old or something. All the other kids were like, Ew, that's ugly! I thought, Wow, contemporary art has this great power! I was interested always in the wrong thing as far as authority was concerned.

On preparing for his 2015 speech at RISD:

I listened to one or two [commencement speeches] for one reason: to see how long they should be, because I had no idea. Whatever everybody else did, cut it [by] five minutes because graduation speeches a lot of times are boring and too long and too well-meaning without any humor. They didn't ask you to be Gandhi, they asked you to inspire the students. So I tried to be very practical in my speech to give inspiration to students — maybe the ones that had the hardest time graduating. The ones that took six years instead of four, or were in rehab for one of those years, or got thrown out and came back in, or had to switch colleges, or barely passed. There's all kinds of graduates and the damaged ones were who I was speaking to.

On his advice to young artists to wreck what came before:

I mean that in a very positive way. By wrecking something, it's always reinventing. All modern movements in art and music wrecked what came before, in a way — and surprised the cooler generation that was one step ahead. That's how you get ahead. Don't get on your parents nerves. Get on the kids two years older then you in school that are the coolest ones. Make them nervous and that way you come up with something new and funny and you become the new leader.

On dealing with bad reviews:

I built a career on negative reviews. That was at a time when that was possible. Today, all film critics are too hip to give you that ammunition. There are no more Rex Reeds, the ones that come out and give you terrible reviews that are hilarious, that you embrace and that all your fans love because they can't stand his reviews in the first place. Today, when you're young and you get a bad review, you're just glad somebody noticed. You've never been reviewed before. Bad reviews hurt much more later in your career. That's when you've already done stuff and you've been working for years and it's much harder to accept. You should never react to a negative review, because as soon as you write a letter to the editor, the original critic gets to answer that. They always get the last word. So if you don't like the heat, get your head out of the oven — or whatever that expression is — because you're always going to get negative reviews. That's part of show business, a life of praise and rejection, and you can't control it.

On the Change.org petition to make him head of the National Endowment for the Arts and his views on government funding for the arts:

Well I'm certainly for it. I always wonder when I'm in Europe, How do all these great feel-bad art movies get made? How could they possibly get financed? They lose money. The reason is because the government pays for them. Can you imagine the government of America supporting a Todd Solondz movie or a Harmony Korine movie? But they should! So I would have free movie stamps, I would give budgets to the most obscure independent films that need the help. Somehow I don’t think Donald Trump’s gonna ask me, but I have lots of political advice I could give.

To hear the full interview with John Waters, click the blue player above.