The Institute of Mental Physics, founded near Joshua Tree as a sort of utopian society, happens to be the largest single collection of buildings designed by architect Lloyd Wright, the son of Frank Lloyd Wright. ... There have been many exhibits of Roy Lichtenstein’s work. But our critic says The Skirball Center’s new show stands out because it pairs the pop artist’s work with the comic book illustrations that inspired it, and they deserve the share the spotlight.

The Institute of Mentalphysics : A seeker and a famous son build a city in the High Desert

"With their oblique angles, rubble stone masonry and long low lines, these structures settle into the desert like shards of heavy quartz exposed by recent floods." -- Architectural historian Eric Davis

On 420 acres on the outskirts of the unincorporated town of Joshua Tree, a vast complex of odd, angular buildings bleaches in the High Desert sun. It’s the Institute of Mentalphysics, also known as the Joshua Tree Retreat Center.

The Institute broke ground August 23, 1946, and is equal parts a mystery and a dream.

The dream began with Edwin J. Dingle, a British expat, naturalized American, wayfaring adventurer, and spiritual seeker. Dingle was an eyewitness to China's Boxer Rebellion and to the revolution that overthrew China's emperor a decade later. He wrote the first book on the founding of the Chinese Republic, and in 1910, travelled to Tibet and stayed for nine months. Expensive maps and almanacs based on his travels became the standard reference books on China for decades.

Dingle relocated to California. He withdrew from public life for six years, and then re-emerged as "Ding Le Mei," architect of a new philosophical movement: a non-denominational hybrid of Christian and Tibetan mysticism called "The Science of Mentalphysics."

Dingle wasn't the only one who saw California as a place for new beginnings. In Los Angeles, another man for whom the Institute of Mentalphysics was also searching. He was Frank Lloyd Wright, Jr. and struggled for years to make a name for himself in architecture, to step out of his father’s shadow. He eventually dropped the “Frank” to try to differentiate himself from his overbearing, visionary father.

His father was a globetrotter with signature works in LA, Tokyo, Manhattan, Chicago, Scottsdale. But California wasn't just Lloyd's home, it was his canvas: his major creations were all built within a 75 mile radius, with Riverside California at its center.

The largest concentration of Lloyd Wright’s work is at the Institute of Mental Physics, and the story of how they came to be - and whether Frank Lloyd Wright Sr. had a hand in designing the buildings there - is the subject of this new audio work from Off-Ramp contributor R.H. Greene, “Elevations: Frank Lloyd Wright Sr. and Jr. in California’s New Age.”

Even in unfinished form, the Institute of Mentalphysics remains one of Lloyd Wright's signature achievements. They suit the Mojave plateau they were built to inhabit as though they were born there.

Lichtenstein and his inspirations, finally, side-by-side at the Skirball

What was the lowest profession in America 60 years ago? Bartender, drug-dealer, whore ... newspaper reporter?

It was comic book artist.

Ever since Superman’s 1938 debut, the comic book flooded the basements of American literature. Superman, Captain Marvel, and Captain America won World War 2 a thousand times over and followed US soldiers all over Europe. But by the mid-50s, comics were seen as a lurid threat to youth: A prominent shrink condemned them as the “Seduction of the Innocent.” Comic books disgusted decent Americans.

And then along came Roy Lichtenstein, who died in 1997 and is the focus of a new exhibit at the Skirball Center. He turned the very spirit of comic books into the cutting edge of the avant garde.

An art-loving public frustrated by a decade of abstract impressionism and one-color canvases eagerly lapped up Pop – especially Lichtenstein’s version -- with its commercial dot shadings and dialogue balloons, agreeably evoking the comics of people’s childhoods. The style was both adventuresome and nostalgic … adventuresome in that it was fraught with comic-book sobbing girls and exploding airplanes, nostalgic despite the way it framed the over-familiar with satire.

The Skirball’s new show, “Pop for the People,” has a lot of virtues, but to me, the prime one is how it opens the connection between Lichtenstein and the comics illustrations that made his work possible. The source-material comics that Lichtenstein exaggerated into his most successful early work are also on display here, where they belong.

This includes the work of people like Irv Novick, whom Lichtenstein encountered as a soldier in Europe, and whose later “All American Men at War” comics were among those Lichtenstein riffed on to produce such early, influential works as “Whaam,” a lithograph of a fatal fighter-plane duel with a four-color hard-edged explosion.

Jazz was just as important an influence. Lichtenstein, who seriously studied sax in his later years, often said so. One need no more critique Roy’s version of “Whaam” in favor of the original than put down Coltrane’s version of “My Favorite Things” in favor of Rogers & Hammerstein’s. Of plagiarism charges, Lichtenstein said, “My art always reflects the art of others.’’ The comic artists he riffed on — many of them never originally identified by their publishers — did not complain. “These are riffs on a theme,” his wife Dorothy said. Later he would even riff on great artists.

Lichtenstein himself said, “The purpose of my art is to show you there might be value in certain things that might be considered valueless.” Instead of digging further into the metaphysics of the human subconscious like the abstract impressionists, he dug into the subsoil of American culture, where he struck the vein of comics, advertising, magazine illustration and exalted them all into art.

He invites us to live in this art. There is a lithographed living room complete to the finest detail; and an Oval Office. They are giant comic panels we could exist in. The most effective of these is an actualization by Skirball artisans of Lichtenstein’s version of Van Gogh’s picture of his “Bedroom at Arles.” It’s reproduced in all its bright yellows and blues in three dimensions, so you can walk into it and even stretch out on Van Gogh’s bed.

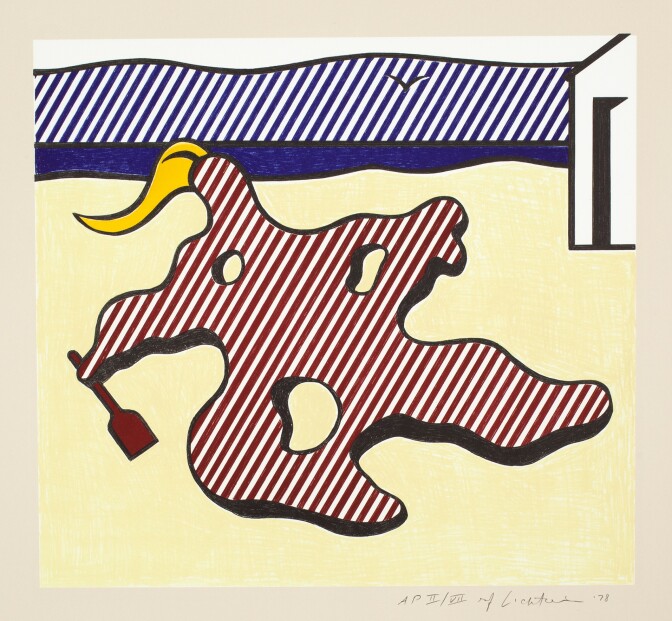

Not all of his riffs on great painters work as well. “Nude on the Beach” seems simply a parody of a parody; the Picasso-inspired bulls imbibe of Picasso’s force without yielding Lichtenstein’s own. On the other hand, the successive magazine covers of a campaigning Bobby Kennedy and a hand holding the smoking gun that killed him have not lost an iota of their power over the past 48 years. The punch of the assorted Lichtenstein dry goods—frocks, shirts, dishes, shopping bags et al, has faded badly, though. These objects have a yard sale look about them.

Most of Lichtenstein’s work originates as reproductions - prints, lithographs and silk screens - and are, in effect, a collaboration with another half-dozen skilled artisans, which is why the role of Los Angeles’ Gemini workshop is so properly stressed in this show. They were a partnership, they enabled him, and he pushed them to expand their technology past it limitations. For the giant Living Room interior, Gemini had to totally revamp its presses to accommodate this interior blue fantasy very much the size of a large wall. All things considered, it’s surprising that the working partnership is recorded as so amiable—even joyous.

But this also makes Lichtenstein, as critic Robert Hughes once put it, “The paragon of the commercial artist,” to the extent that his art can be said to be manufactured, rather than created.

As far as I know, Lichtenstein did not object to this characterization. He very well might have seen himself as a great artist who was also commercial. Just like his key inspiration, the humble, stirring comics of his youth.

"Pop for the People: Roy Lichtenstein in L.A." is at the Skirball Cultural Center through March 12.

Song of the week: "The Ruins" by: Phillip Glass

This week's song of the week comes from Philip Glass. It's Act 3 Scene 3 of his opera Akhenaten, which is being staged by LA Opera.

Here's the Opera's synopsis: In ancient Egypt, Akhnaten ascends to the throne along with his bride Nefertiti. He has a vision for his people, a vision that abandons the worship of many gods for just one: the Sun God who reigns supreme. Akhnaten's bold attempt to alter the course of history with a single revolutionary idea ultimately leads to his violent overthrow. I would have said, "spoiler alert" but it's opera. It always ends badly.

Akhnaten has one more performance at LA Opera on November 27. It's sold out, but who knows? Tickets might free up closer to the day.

Pio Pico: A life as big as the 2-time governor's needs 2 graves

"What are we to do then? Shall we remain supine, while these daring strangers are overrunning our fertile plains, and gradually outnumbering and displacing us? Shall these incursions go on unchecked, until we shall become strangers in our own land?" -- Pio Pico

Rags-to-riches-to-rags stories are common in the fabric of Southern California history. They're"quintessential," says Carolyn Christian of the Friends of Pio Pico.

Pio Pico, the last governor of Alta California under Mexican rule, was a revolutionary who at one point made the missions forfeit their land. He also bet tens of thousands of dollars on horse races, but at the time of his death, couldn't afford his own grave.

Pio de Jesus Pico was born on May 5, 1801 at the mission San Gabriel Arcángel. California in this era had a tightly stratified caste system with indigenous people at the bottom, Mestizos (Mexicans with European blood) in the middle, and Spanish rancheros at the top, making up a mere 3% of Alta California's total population, according to historian Paul Bryan Gray. Pico himself came from Spanish, African, Native American, and Italian descent, but thanks to his father's service in the Spanish army, he had the potential to be part of the landowning class.

(Pio Pico, 1858. UC Berkeley, Bancroft Library)

"The elite became the elite because they were the descendants of the original soldiers sent to California in 1769," says Gray. "The way things worked was that if you had an ancestor who did military service, or if you did military service yourself, you would get a land grant."

Eligibility was important, but availability came first. The Catholic Church controlled most of California's arable land through the missions. By the 1830s, upheaval was fomenting throughout the ranchero class, who were eager to expand their holdings by secularizing the mission lands for use by civilians. Pio Pico found himself at the head of a small rebellion and met the anti-secular Governor Manuel Victoria in combat at the Battle of Cahuenga Pass on Dec. 5, 1831.

Victoria was one of the very few injured in the battle, and didn’t return to his post. Pico "was elected to the Assemblea, what we'd call the state Assembly today," says Gray. He held office for 20 days in 1831 until the Mexican government pushed him out. The popular movement of secularization had taken hold though, and Pico and his brother Andres secured massive tracts of land in the San Diego and San Fernando areas, and after the Mexican-American War, in the San Gabriel Valley.

Pico married his wife, Maria Ygnacia Alvarado, in 1834. The two never had children together, but adopted two daughters. Carolyn Christian says that Pico fathered these children with other women, and legitimized them through adoption. Maria Ygnacia was the niece of Juan Bautista Alvarado, the Monterrey-born governor from the north who held office from 1836 to 1842. When Alvarado was succeeded by Mexico’s Manuel Micheltorena, Alvarado and Pico joined forces with another former governor, Jose Castro, in an uprising that culminated in the Battle of La Providencia in 1845.

Governor Micheltorena was overthrown and Pico retook the governor’s mansion, this time with Mexico’s blessing. One year later, the United States declared the Mexican-American War, and Gray says Pico accomplished little in this time. Pico had written about the increasing throngs of settlers from the Southern states coming to California leading up to the war:

"What are we to do then? Shall we remain supine, while these daring strangers are overrunning our fertile plains, and gradually outnumbering and displacing us? Shall these incursions go on unchecked, until we shall become strangers in our own land?"

"Pio Pico actually left California, went down to Mexico, and there are a couple stories why," says Christian. "Some people say he was a coward and he was running away. Other people say, no, he was going to down to Mexico to get reinforcements to come up and fight the Americans. The other reason why people think that he left is because if you have a head of government, and they're captured, you have a lot of negotiating power. So if they're gone and they can't be captured, that helps from having something leveraged against you."

Mexico ceded California and the rest of the Southwest with the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in February 1848, signed at the Cahuenga Pass — the very site of both of Pico’s rises to governance. Pico returned to Los Angeles the same year.

"When he returned to California, he announced, 'I'm back, I'm governor of California.' And of course he was immediately thrown in jail," laughs Christian. Pico was bailed out by William Workman, says Christian, and became a proud member of the new Californian society. He was elected to the L.A. City Council, but never took office, says Gray. He continued building up a fortune in land holdings and gained a windfall from cattle raising because of the Gold Rush's high beef demands.

Maria Ygnacia Pico died in 1854, but Pio Pico would live on for another 40 years. In the 1860s and '70s he had two more children — sons — and in 1870 he made his last grand business venture: The Pico House. It was L.A.'s first three-story building and luxury hotel, with 33 suites, designed by architect Ezra Kysor, and still stands at El Pueblo de Los Angeles. Pico lost the hotel to the San Francisco Savings and Loan Company in 1876.

(L: Pico House, est. 1870, 400 block of LA's Main Street. R: Merced Theatre, erected 1870, L.A's first playhouse. Konrad Summers/Flickr Creative Commons)

Pico’s resources dwindled swiftly in the 1880s. His ranch was damaged by floods, he gambled away as much as $25,000 on a single race, and his son and translator Ranulfo was murdered for leaving a woman at the altar.

"He never bothered to learn English, so he couldn't read the deeds and mortgages and other documents given to him," says Gray, and Christian adds, "There was a lawyer by the name of Bernard Cohn, who actually swindled a lot of the Californios out of their land. He did it by presenting them with what they thought were loans, and they were actually signing over their ranchos... It went all the way to the California Supreme Court." Gray calls this the last in a long string of risk-taking by the ex-governor, "and as a result he lost all his land in Whittier and finally died in total poverty because of his negligence."

Pico died on Sept. 11, 1894 at 93 years old. He was buried at the first Calvary Cemetery, L.A.'s original Catholic cemetery, which was founded in 1844 and condemned due to massive disrepair in 1920. Pico and Maria Ygnacia Alvarado were interred in an above-ground tomb with cast iron markers, and at one point Alvarado's skeleton was grave-robbed and left strewn some 50 feet away, according to the L.A. Downtown News. The cemetery and most of its occupants were relocated to Calvary's current location in East L.A. in the '20s.

(Pico Family tomb at Old Calvary Cemetery. LAPL/Security Pacific National Bank Collection)

Cathedral High School now occupies the site the original Calvary Cemetery stood on. Pio Pico was moved not to East L.A., but to the Workman-Temple Homestead in what was known as Rancho La Puente. Pico had granted William Workman massive land tracts for serving in the Mexican military during the Mexican-American War, and when his great grandson Thomas Temple found oil on his family's property, Workman's grandson Walter Temple built a mausoleum for friends and family — which is Pio Pico's final resting place.

Visit Pio Pico's tomb at the Homestead Museum, which is giving a special presentation and tour at the Walter P. Temple Memorial Mausoleum on Sunday, Oct. 25.

The social worker who rescued Taylor Orci from child abuse

With the Los Angeles County Department of Child and Family Services on the hot seat once again after another child it was monitoring was killed by a family member, Off-Ramp commentator Taylor Orci remembers the County social worker who rescued her.

I was standing outside my fourth grade classroom when my teacher told me to lie.

A few days before, my teacher had asked me if anything was wrong. Creative writing was my favorite subject, and a disturbing story I had written about vampires had led her to ask me if I was having problems at home. I was.

I told her about not having enough food to eat, seeing body parts I shouldn't have been seeing. I told her about my favorite hiding spots in my house where I'd go when I felt like my life was in danger — under the wicker loveseat because it made me feel like I was at a tea party.

The answers gushed forth. I mean, why wouldn't they? The TV always said to tell a trusted adult if something was wrong, and Mrs. Palmer was an adult I could trust — after all, she made sure my clay cheetah didn't break in the kiln that one time during arts and crafts.

And now I was standing outside the classroom where I confided in her, next to my dad who'd shown up without me knowing. Both of their faces looking down on me with equal parts worry and disapproval.

"Tell your teacher you made this up," said my dad.

"I made it up," I told my teacher.

"Tell your dad you're sorry," said my teacher.

"I'm sorry," I told my dad.

"She has a wild imagination," my dad said.

"Oh I know, what stories!" said my teacher.

And then my dad took me home and we never spoke of it again.

Until a few months later a miracle happened.

I was playing handball outside with my next door neighbor when a man in a white car with the county seal of Los Angeles drove into our cul-de-sac in La Verne. Our tranquil suburb was what Vernon Howell used as a kind of test kitchen for his Branch Davidians before he went down in a blaze of glory in Waco as David Koresh. We were full of secrets.

The man had a black mustache and asked if my dad was home. I told him he was. I thought he was his friend. I was 9; I thought all men with mustaches were friends.

My neighbor and I kept playing handball as the sun turned the sky colors that matched my bright purple handball. I had almost forgotten there was a man in my house until he came out with my dad. I saw the look on his face, the same combination of worry and disapproval he had before. I knew this man wasn't his friend.

"Sweetheart, this man wants to ask you some questions," my dad knelt down and looked me in the eyes so intensely I thought I would shatter into pieces. "And whatever you do: tell him the truth." I waved goodbye to my next door neighbor and told him I'd see him tomorrow. I didn't know I wouldn't see him for three years.

The man took me to my room and explained he was a social worker. He told me a family member had told their therapist about my situation and the therapist called the county and sent him. He asked me to tell the truth.

I remembered my dad telling me the same thing, and where telling the truth got me the last time I did it. And despite my better judgment, I told him everything I had told my teacher months earlier. Then he told me to pack my bag because I was going to live with my mom and stepdad.

Driving to my mom's house, I felt so grateful for that man with the mustache. I had become so used to not trusting adults, but this social worker proved you could in fact trust some adults — just not all of them.

I wanted him around all the time to make sure I didn't get hurt. I asked if we could keep in touch. I had a pen pal that lived in Oregon so I knew I was good at it. He said thank you, but that wasn't possible. I remember sitting in the backseat of his county-issued vehicle, which to me was as good as a prince's white horse, knowing my life was about to change. I just didn't know how.

I know I had one of the good experiences, I know there are many more that are tragedies upon horror stories. I just hope more stories will end like mine, and not like the ones that become headlines… about children with no adults to trust, kids who try to save themselves, over and over again.