Come with us to the sign spinning championships in Vegas ... Easter Eggs in animated films ... Brains On, the science podcast for kids ... the Griffith of Griffith Park was a very nasty man ...

The World Sign Spinning Championships: How one company turned street ads into a competitive sport

It’s probably happened to all of us: you pull up to a red light at a busy Southern California intersection. Your eyes wander to the street corner and there's a guy with a sign advertising some local tax place, burger joint or loan office. Then, all of a sudden, he’s spinning the sign behind his back. He does a backflip, then throws the sign into the air. Just when you think it’s about to land in traffic, it falls right back into his waiting hand — and you’ve nearly missed your green light. What you’ve just witnessed is the work of a company that’s changing what it means to be a human billboard: AArrow Sign Spinners.

When company founders Max Durovic and Mike Kenny started working in sign spinning, a form of on-the-street marketing, they were teenagers. They worked outside a San Diego housing development. They weren’t even called sign spinners, but "human directionals."

“We were just bored!” Durovic says. “I think the first day Mike and I worked across the street from each other, you know, it was like, ‘Who can spin it faster, who can throw it higher?’”

Boredom and a competitive nature created something between the two friends. They taught each other how to spin the sign behind their backs, then throw and catch it. That summer in San Diego, with the 1998 X Games just down the street, an extreme sport and an advertising company was born.

“We really tried to make it more extreme and more fun and spice it up, and it really started to work. Clients came to us and said that their traffic was increasing,” Kenny said.

In their first years at college, Max and Mike founded AArrow Sign Spinners, a self-described guerrilla marketing company based in North Hollywood. Today, over 2,500 AArrow employees are spinning in 35 cities and 11 countries. Last year, the company had a revenue of $9.1 million.

“We’ve placed ourselves as the professionals,” Kenny says. “So, anyone else that’s out there and is spinning signs on their own, or is trying to start their own company, we go to them and say, ‘Hey, AArrow should be the home for anyone that really cares about sign spinning and really cares about doing this the right way.’”

To spin signs the AArrow way, employees must learn from the "tricktionary" — a book of hundreds of very specific and copyrighted tricks that only AArrow-certified "spinstructors" are allowed to have.

Why all the secrecy?

“It’s our spintellectual property,” Durovic says.

Almost all AArrow spinners are male, and almost all of them start spinning in their teens. Since sign spinning only makes advertising sense on heavily trafficked street corners, most employees come from urban centers. The AArrow founders are very much aware of this.

“I think youth unemployment is something that faces every area of this country, and that if we can solve that, that helps reduce teen pregnancy and crime rates,” Durovic says. “So, spinning signs is probably a much better thing to be doing on that street corner than anything else.”

Sign-spinning to stop crime may seem like a stretch, but not to some of their oldest employees like Mike Wright of San Diego, who’s been with AArrow for 10 years.

“I was never living on the street, but I was living in a bad part of San Diego. I mean, meth dealers and everything—a meth fire happening right next to our house,” Wright says. That fire forced Wright and his mom to abandon their home when he was 16 years old.

“Thanks to AArrow, I was able to get a first check; and me and my mom, we got right out of there, we moved,” Wright says. “If it wasn’t for AArrow, we’d pretty much be doing the same thing.”

Wright says he loves to spin signs, not as a job, but as a culture and a sport. Which may have something to do with the World Sign Spinning Championships.

Every year since 2007, AArrow CEOs and employees meet, this year in downtown Las Vegas, for the World Sign Spinning Championships. One hundred and ten AArrow employees from around the world, who all won their regional competitions, are here to spin for the title and $1,000 cash prize.

For the AArrow founders, the global competition is something they’ve dreamed of since day one.

“From the very beginning, I think it was all about the competition for us,” Kenny says.

“Definitely,” adds Durovic. “The NBA, the NFL — we wanted to run a sports league.”

Amid deafening chants of “AA-RROW!” the spinners prepare for a weekend marathon of sign-spinning. There are two rounds, and spinners compete twice in each. They are judged on style, energy, technicality, foot placement, audience interaction and other criteria. And that’s all before the finals.

Only five make it into the final round. Mike Wright is one of them. But there is one competitor who, literally and figuratively, stands head and shoulders above the rest: Kadeem Johnson.

Johnson, who is over six feet tall, moved to the U.S. from Jamaica when he was a kid. By his late teens, he was living with his family in Tampa, Florida, and in need of a job. His brother showed him videos of AArrow sign spinners and told Kadeem they were always hiring.

Six years later, Johnson is a two-time winner of the World Sign Spinning Championship. But he is hungry for more.

“I’ve already won twice, but I want to win three times,” Johnson says, with a determined and excited energy. “I want to win again. I want to be the Michael Jordan. Like, Michael Jordan has six rings, let’s get seven, right?”

Johnson laughs. He knows that if he wins today, he’ll be the first sign-spinner in history to win the championship three times. He knows a win today will make him a legend within AArrow. Suddenly, he turns serious.

“Next year, I don’t care who wins. But this year, I need that — I need that number one spot,” Kadeem says.

As the sun sets on Fremont Street, the final round starts. Johnson is the first up.

With Katy Perry’s “Roar” in the background, Johnson throws his sign in the air and it returns right to his waiting hand. He does a handstand with the sign between his legs, and then gets on the ground, pulling out break dance moves he learned as a kid while spinning a sign in one hand. His best trick, however, is his presence — he exudes confidence and positivity, with a beaming smile and eye contact that makes his one-minute set a true Las Vegas show.

And it makes Kadeem Johnson a three-time champion.

After being announced the winner of the 2016 World Sign-Spinning Championship, the crowd swells in applause, and his fellow spinners rush the ring to hoist Johnson in the air. There are cheers, there are chants, but the spectators are already being pushed aside to make room for a clean-up crew. The AArrow banners come down and the ring disappears. Within a matter of minutes, the street returns to the foot traffic, and the spinners disperse.

There isn't a whole lot of time to celebrate. They all have to work on Monday.

Gagosian show from Alex Israel, Bret Easton Ellis 'cynical, lazy,' critic says

In the LA Times, David Pagel criticizes the new offering at Gagosian Gallery, a collaboration by artist Alex Israel and writer Bret Easton Ellis:

What looks good from the driver’s seat doesn’t necessarily look good up-close and in person. Just about every one of their 16 images, which range in size from 6- to 14-feet on a side, would be better as a billboard. - LA Times

Mat Gleason, of Coagula Curatorial, told Off-Ramp the work would be better not as roadside billboards, but as roadkill.

"I wish Bret Easton Ellis had just done this as a stand-up comedy act. The one-liners might have worked; maybe they're rejects from Saturday Night Live's series The Californians. The whole thing just reeks of laziness and cliche."

For Gagosian, which Gleason says is "obviously the number one gallery in the world relative to its size, its scale, and its scope," Ellis, the podcaster and author of "Less Than Zero," provided pithy lines that echo LA cliches:

- I’m going to be a very different kind of star.

- In Los Angeles I knew so many people who were ashamed that they were born and not made.

- Somewhere in the empty house Jenn could hear The Eagles singing Hotel California, its deep and hidden meanings revealing themselves in waves.

Then Israel matched them with stock images of Southern California - the downtown skyline, a foggy Malibu scene, etc., as Gagosian's website explains:

The city of Los Angeles is both background and subject in the respective oeuvres of Israel and Ellis. For Israel, the American dream, as embodied by the Los Angeles mythos, remains affecting and potent. Channeling celebrity culture as well as the slick appearance and aspirations of the entertainment capital, Israel approaches his hometown with an uncanny coupling of local familiarity and anthropological curiosity. His work alludes to both California cool and calculated brand creation, embracing cliches and styles that exude the hygienic optimism endemic to the local scene.

"It's pathetic," Gleason says, "that Gagosian has stooped to undergraduate jargon. Alex Israel is an anthropologist?!"

Since Israel and Ellis are both natives who presumably know LA is richer and far more nuanced than the caricature they present, I asked Gleason if maybe this is an ironic, meta commentary on the people who hold these beliefs about LA?

"Commentary can't be this calculated. Here's the thing. You have wealthy art collectors moving to Los Angeles and they're not immersed in Los Angeles as we know it. They're clinging to the stereotypes of Los Angeles as they know it. It sounds like I'm just being cranky, but you actually have to be bold now to give any criticism to this work because there's the whole insider notion that 'Oh, you just don't get it.' I get it completely."

Listen to the audio for my readings from the art, and more of Mat's take(down).

Song of the week: "Ee Chê" by Anna Homler and Steve Moshier

This week's Off-Ramp song of the week is called “Ee Chê" and it was recorded in the early 1980s by artist and singer Anna Homler and composer Steve Moshier. It's the first track off their project "Breadwoman, and Other Tales" re-released last month on RVNG International. It's a strange record with an even stranger story.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_kaDdFrI6n4

Homler is a visual and performance artist and was of L.A.'s Otis College of Art and Design when, driving around Malibu and Topanga, she started writing songs in an invented language. When she performed the songs, she created a new persona: "Breadwoman."

Breadwoman was an ancient cowled figure with loaves of bread where her face would be. Check out the documentary on the recordings:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ssf7fR5bfeU

A short master class on music writing from New Yorker critic Alex Ross

Alex Ross, music writer for The New Yorker, joined me in the Off-Ramp studio to talk about the artcraft of music writing.

Ross is probably responsible for more of my iTunes purchases than any other writer. Invariably, when I read his pieces, I buy the album.

Ross has a way of getting to the emotional core of the music he's writing about:

To hear the entire corpus is to be buffeted by the restless energy of Bach’s imagination. Recently, I listened to around fifty of the cantatas during a thousand-mile drive in inland Australia, and, far from getting too much of a good thing, I found myself regularly hitting the repeat button. Once or twice, I stopped on the side of the road in tears.

— "The Book of Bach" by Alex Ross in The New Yorker

And Ross has a deft hand at explaining technical music terms so that the novice can see how music works:

We can all hum the trumpet line of the “Star Wars” main title, but the piece is more complicated than it seems. There’s a rhythmic quirk in the basic pattern of a triplet followed by two held notes: the first triplet falls on the fourth beat of the bar, while later ones fall on the first beat, with the second held note foreshortened. There are harmonic quirks, too. The opening fanfare is based on chains of fourths, adorning the initial B-flat-major triad with E-flats and A-flats. Those notes recur in the orchestral swirl around the trumpet theme. In the reprise, a bass line moves in contrary motion, further tweaking the chords above. All this interior activity creates dynamism. The march lunges forward with an irregular gait, rugged and ragged, like the Rebellion we see onscreen.

— "Listening to Star Wars" by Alex Ross in The New Yorker

Listen to the audio for the full interview, including music excerpts that illustrate what we're talking about.

5 classic Easter eggs from your favorite animated movies

On Easter Sunday, little kids will be searching under bushes and inside closets for hard-boiled, chocolate, and marshmallow Easter eggs. But Off-Ramp animation expert Charles Solomon says animation fans can find Easter eggs every day of the year — provided they know where to look in their favorite movies.

"The beauty of these films is we try to layer them. We try to make them very thick … you know, like a very good deli sandwich. So that audiences won’t just watch it once and then forget about it. They’ll go back and look at it again, and again, and again. And every time they look at it, they see something else; they spot something new." —Disney Animator Tom Sito

For animators, an Easter egg is an in-joke, a caricature, or some other surprise hidden in a movie. Disney animator Eric Goldberg says the practice goes back at least to the 1930s: "You can look at 'Ferdinand the Bull,' for example, from 1938, and there’s a scene where all the characters are caricatures of staffers. There’s Ward Kimball, there’s Art Babbitt, there’s Freddie Moore, and at the end, the matador himself is Walt Disney. If Walt can take a joke, then so can we."

(Walt Disney himself was caricatured in the 1938 short "Ferdinand the Bull.")

1. In the classic Warner Brothers cartoon "Rabbit of Seville," the cast is listed on a sign at the entrance to the Hollywood Bowl: Eduardo Selzeri, Michele Maltese and Carlo Jonzi. That is: producer Eddy Selzer, writer Mike Maltese and director Chuck Jones.

Watch "Rabbit of Seville," set at the Hollywood Bowl, complete with crickets!

2. At the end of "One Froggy Evening," the demolished building whose cornerstone holds the box with the singing frog is named for sound effects artist Tregoweth Brown.

(In this scene from Warner Bros.' classic "One Froggy Evening," great sound effects are timed to occur as the Easter egg pays tribute to the short's Foley artist.)

3. When animation artists are designing minor characters for a film, it’s easy and fun to draw family members, the boss, or the guy in the next cubicle. In "Aladdin," Disney animator Tom Sito was assigned to animate himself.

Sito is Crazy Hakim, the discount fertilizer dealer seen at the end of the song “One Jump Ahead.”

John Musker, who co-directed "The Great Mouse Detective," "The Little Mermaid," and "Aladdin," calls Easter eggs “the spice in the soup.”

(L-R: Co-directors John Musker and Ron Clements always put themselves in their movies, as in this scene from "Hercules.")

But despite his success, he doesn't always get his way. "In 'Aladdin,'" Musker says, "when Jafar was opening the Cave of Wonders, he originally said, 'Rasoul Azadani!,' which was the name of one of our layout supervisors; he’s Iranian. And one of our creative executives said, 'No, no. You can’t put his name in the film.'”

4. Easter eggs can also serve as homages. Brad Bird put his mentors Frank Thomas and Ollie Johnston, the last of Disney’s “Nine Old Men,” in both "The Iron Giant" and "The Incredibles."

The trick is to place Easter eggs where they won’t distract regular audience members, but where fans can find them and get the reward.

5. The “Rhapsody in Blue” segment of "Fantasia 2000" is a whole basket of Easter eggs. If you single-frame through the sequence where a crowd pours through the revolving door of a posh apartment building — named The Goldberg — you’ll see caricatures of director Eric Goldberg, his wife Susan, other artists who worked on the film … and a bustling bearded character who resembles a certain animation critic.

(A scene from Disney's "Fantasia 2000." That's Charles Solomon on the far right. Animator Eric Goldberg is the small man wearing a bow-tie whose head is obscured by the purse.)

Listen to our bonus audio for exclusive interviews with Tom Sito, John Musker and Eric Goldberg as they talk about Easter eggs and the art of animation.

Editor's Note: In the first version of the audio segment, Rabe used an excerpt of "Long Hair Hare," instead of "Rabbit of Seville." We regret the error.

Happy 120th Griffith Park, but your founder was a jerk

Griffith Park, one of LA’s most beloved spots, turns 120 on Dec. 16. Too bad its namesake was an alcoholic, murderous misanthrope who thought the pope was plotting against him.

Here's the story, from Robert Petersen, who hosts and produces the podcast The Hidden History of Los Angeles.

Griffith J. Griffith was born poor in Wales in 1850. He migrated to the U.S. and moved to San Francisco where he made a fortune in mining. He moved to Los Angeles in 1881 and bought Rancho Los Feliz – a tract that included present day Los Feliz, Silverlake, and part of the Santa Monica Mountains. He married the daughter of a prominent family and started referring to himself as a colonel.

He was an odd man, condescending, long-winded, and unpopular. They said of him, "He's a midget egomaniac, a roly-poly pompous little fellow.”

Unable to charm his way into the hearts of Angelenos, he then tried to use his wealth. In 1896, Griffith gave the city of LA the biggest Christmas gift it had ever received. He donated more than 3,000 acres of Rancho Los Feliz to the city for use as a public park. This became Griffith Park.

But soon Griffith started drinking – as much as 2 quarts of whiskey every day – and arguing religion with his wife. Tina was staunchly Catholic. Griffith was Protestant. And he came to believe that his wife was conspiring with the Pope to poison him and steal his money.

And then in 1903, things came to a head.

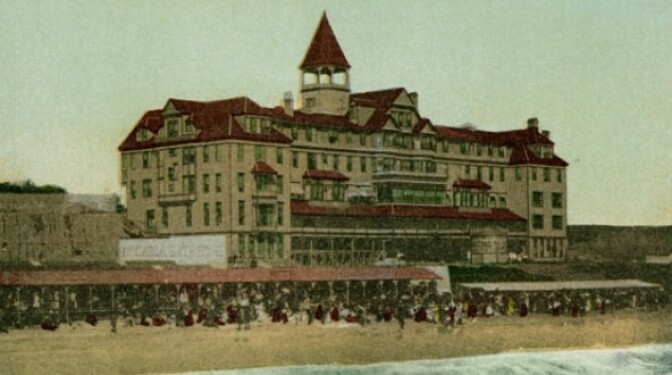

Griffith and his wife, Tina, were vacationing with their 15-year-old son at the presidential suite of the Arcadia Hotel - a seaside resort in Santa Monica.

During their stay, Griffith kept insisting on changing plates and coffee cups with Tina — to stave off any attempt by the Pope, or his wife, to poison him. Then on the last day of their vacation, Griffith entered their bedroom with Tina’s prayer book in one hand — and a revolver in the other.

According to a 1904 article in the Los Angeles Times, He ordered Tina to get on her knees and said: “Remember I am a dead shot.”

He handed Tina her prayer book and ordered her to swear her truthfulness.

Tina described it to the Times:

“He told me to take my prayer book and get down on my knees; that he had some questions to ask me. I begged him to please put the pistol away. Oh, I begged him to please put it away. I saw that I was in the hands of a desperate man, so I asked him if I might have time to pray. He said I might, so I knelt and raised my eyes and prayed.”

Griffith then pulled out a card with a list of questions on it. The Colonel asked the questions as he held the pistol over his wife kneeling before him:

Griffith: “Did you ever know of Briswalter being poisoned in your house?”

Tina: "No, he was not poisoned; he died of blood poisoning brought on from a sore foot. He —"

Griffith: “That will do. Have you been implicated with or do you know of anyone having given me poison?”

Tina: “Why, Papa, you know I never harmed a hair of your head.”

Griffith: “Have you ever been untrue to me?”

Tina: “Papa, you know I never have.”

Griffith took aim with the pistol and started pull the trigger. But just as he pulled the trigger, Tina jerked her head to one side and the bullet struck her in the eye but did not kill her. Bleeding and blinded, Tina jumped out the window and landed on a wooden piazza roof one floor below. She landed next to the window of the couple who owned the hotel and they pulled her to safety. They also called the sheriff.

Griffith was put on trial for attempted murder. His defense attorney argued that Griffith was the victim of “alcoholic insanity” and the jury convicted Griffith of the lesser charge of assault with a deadly weapon and he was sentenced to the maximum sentence possible — 2 years and a $5,000 fine.

His wife filed for divorce and a judge granted her request in less than 5 minutes, arguably the fastest divorce in L.A. history.

After a two-year prison term at San Quentin, Griffith returned a sober and somewhat more humble man, intent to mend his broken reputation. But most Angelenos didn’t want to have anything to do with him.

Before his death, Griffith attempted to rehabilitate his image once again by giving to the city – this time money to build a public observatory and theater in Griffith Park. Some in the city wanted to turn down the money, not wanting to accept anything from a social pariah. But ultimately, the money went to the city after Griffith’s death by way of a trust. The Colonel died in 1919. The Greek Theatre was completed in 1929. The Griffith Observatory was completed in 1935.

Griffith Park, Griffith Observatory, the Greek Theater — all of these L.A. landmarks owe their existence to the Colonel.

And through these gifts to the city, his name has been rehabilitated. Today, the name Griffith is associated with some of the most beloved landmarks of our city. And the near murder of his wife is long forgotten.

Griffith Park, Griffith Observatory, and the Greek Theater, more places where you can find the hidden history of L.A.