Here's a sample from the last year, to remind you why Off-Ramp is unparalleled in bringing you the people, places, and ideas that make Southern California a great place to live ... and worth supporting at kpcc.org!

Remembering Chuck Barris and his tribute to Le Petomane in 'The Gong Show Movie'

Barry Cutler is an actor and Off-Ramp commentator who lives and writes from a desert hideaway. Chuck Barris died Tuesday at the age of 87.

In the late 70s, I was working with Paul Reubens (soon to be much better known as Pee-wee Herman) and a group of other wonderfully talented people in a traveling children's theater company. Paul and I enjoyed improvising together and he was always offering up wonderful suggestions which I was too lazy to take him up on.

When he became a member of The Groundlings' workshops (his launching pad for Pee-wee), I didn't want to waste $35 a month on it. When he invented any number of ridiculous characters and acts to perform on Chuck Barris' "The Gong Show," pitching it as a way to earn an AFTRA day-player's rate, I was too lazy to invent a single act. And, besides, I was too talented for that crap.

Later, when I was given an opportunity to audition for "The Gong Show Movie," I was either less talented or thought the movie would be less crappy. I was not especially looking forward to meeting Chuck Barris. He seemed to me a silly ass who fed his audience garbage. So I was I surprised to meet a very sweet, gentle man.

Barris told me he'd always wanted to do a biopic about the great French farter, Le Petomane - a real-life performer who could take air in, and expel it out, to great effect. He's why Mel Brooks' Governor in "Blazing Saddles" is Governor William J. Le Petomane.

Barris had read a lovely and loving book written by the great flatulist's son and had attempted to get the rights to do the movie. The family, learning of Barris' rather tawdry reputation, refused to allow it, fearing he'd make a mockery of a man (real name, really: Joseph Pujol) who once presented private entertainments to the royalty of Europe.

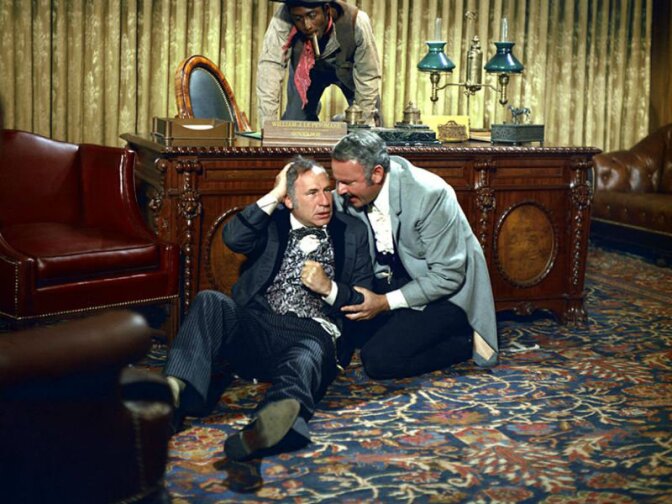

So, not using Le Petomane's name, Barris was going to put the act in his upcoming "The Gong Show Movie" and he cast me as the French farter. It was a small role with me performing -- miming really, since my bowels had no such talent -- several of Le Petomane's tricks. Blowing out a candle at 20 paces. Impersonating a dialogue between a grandmother and her grandchild. All the usual anal tricks.

The Gong Show Movie #3 by NilbogLAND

Once the movie was shot, Barris arranged for a world premiere at the Chinese Theatre. And he went all out. The stands in front of the theater were filled with fans. Everyone in the cast was lined up around the block, each with their own limo. Army Archerd stood on a platform, microphone in hand, prepared to interview each of us for our adoring fans.

When I arrived, I was accompanied by my lovely, blonde, French farter assistant, Sena. When we stepped up to be interviewed by Army, he had no idea who the hell we were and made a point of that. However, he was very politic, asked us a few forgettable questions, and moved on to -- I think -- Steve Garvey.

After the screening, we were all limo'd over to a disco place on Sunset for a big cast party. It may have been the worst movie I was ever in, and I've been in some real, how do you say?, stinkers. But it may have been the most fun.

And, while I can't deny that I never learned to respect the product Chuck Barris offered the public, I learned to respect the man. He was an intelligent, kind gentleman. And, what the hell, he did write

. And that was fun.

Meet the last surviving member of Norco's pioneering veterans wheelchair basketball team

70 years ago, inspiration struck in Southern California that enriched the lives of countless veterans with spinal cord injuries. It was wheelchair basketball, which improved the vets’ physical and mental health, and helped tell their story at a time when disabled people were usually hidden away.

Listen to the audio to hear my conversation with David Davis, who has the story in the latest edition of Los Angeles Magazine, and Jerry Fesenmeyer, the last surviving member of The Rolling Devils, a team of paralyzed vets from the U.S. Naval Hospital in Norco.

Fesenmeyer, now 90 and living in a small town in Texas, was paralyzed by a Japanese sniper bullet near the end of World War 2. I asked what his treatment was like, and he laughed. "Let's put it this way, almost non-existent."

If Fesenmeyer had suffered a spinal cord injury prior to World War II, he likely would have died either from the trauma itself or from infection. The few paraplegics who survived in those days were shunted off to hospitals and ordered to remain flat on their backs. Then came penicillin and improved surgical techniques, both of which vastly increased the survival rate of the severely wounded. And long-term treatment began to change, too—albeit not right away. After peace was declared and Fesenmeyer was brought stateside, he landed at the U.S. Naval Hospital Corona in the Riverside County town of Norco, some 50 miles east of downtown. “In the beginning they didn’t know how to take care of us,” he says. “They believed if you had a spinal injury, you weren’t supposed to get out of bed for a year. I laid in that goddamn bed just rotting away.”

That scenario was changing, though. Doctors were developing a revolutionary, if counterintuitive, way to rehabilitate paralyzed vets: through exercise and, in particular, wheelchair basketball. The sport was born in Southern California and later helped launch the Paralympic Games, which celebrate their 56th year this September in Rio. Fesenmeyer was among the pioneers. At 90, he’s the last surviving member of the Rolling Devils, one of the first organized sports teams for disabled athletes. The Devils sold out arenas and transformed not only the public’s perception of paraplegics but paraplegics’ perceptions of themselves.

-- David Davis, Los Angeles Magazine

Jerry is typical of the Greatest Generation: the most he'll admit about playing wheelchair basketball is that it "got him out of bed." But it also gained him his first wife - a high school girl who came to a game in Corona - and for the public, it was an important wake-up call that people in wheelchairs are people with lives to lead.

LA Mayor Bowron's role in the Japanese American internment

December 7, 1941 was "a date which will live in infamy," but just two months later FDR himself was responsible for an infamous date. He signed signed Executive Order 9066 on February 19, 1942, forcing 120,000 Japanese Americans from their homes.

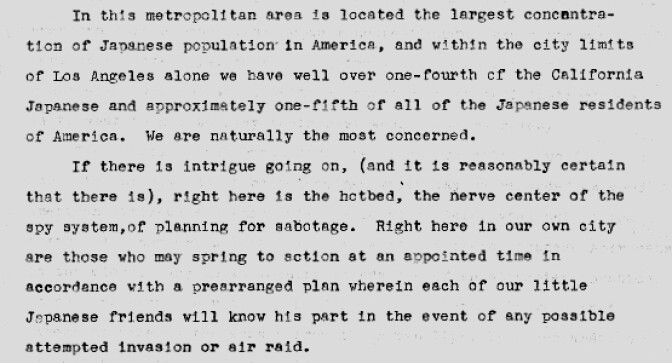

To mark the 75th anniversary of the order, LA City Archivist Michael Holland tells us the story of Mayor Fletcher Bowron's support for the criminal mistreatment of so many of his city's citizens.

Certainly, some way should be devised for keeping the native-born Japanese out of mischief. I feel that this could be handled on the theory that the burden is upon every American-born Japanese to demonstrate his loyalty to this country, to show that he really intends for all time, in good faith, to claim and enjoy one citizenship rather than dual citizenship. Since the question to be determined is whether there is a mental reservation in his declaration, it would, of course, take considerable time to make the necessary investigation, possibly as long as the war would last, and during the period of such inquiry, while the question of loyalty may be in doubt, so long as there may be a possibility of an American-born Japanese having hidden in the secret of his mind an intention to serve the Mikado as a loyal subject of Japan, when and if such occasion should arise during all of this period the American-born Japanese might be well engaged in raising soy beans for the Government.

— LA Mayor Fletcher Bowron, 2/5/1942, KECA Radio

World War 2 made LA into the metropolis it would become. People came here in droves for work in the defense industry and many of them stayed for the weather and lifestyle. But that success story has a very dark side which we are still grappling with, and some of the proof is in the LA City Archive.

The archive contains radio speeches Mayor Fletcher Bowron made every Thursday night. Alas, there are no audio recordings of these speeches, but there are paper transcripts that let us recreate what they might have sounded like. (Listen to the audio player to hear actor Christopher Murray read excerpts from Bowron's radio speeches.) In many of them, Bowron supports the Japanese Internment and details how and why it would be carried out.

Bowron was elected in 1938 to replace the corrupt Frank Shaw, and instituted reforms to restore confidence in local government. He used the radio as a bully pulpit to call out other politicians who were resistant to his agenda. He was re-elected in 1941.

Then came the attack at Pearl Harbor, which bred a special hatred towards the Japanese living here in Southern California, many of them American citizens by birth.Los Angeles was at the center of the war effort, with the Ports of LA and Long Beach, oil refineries, and the factories producing the materiel needed to defeat the Axis Powers. In mid-January, 1942, Mayor Bowron had been told about a plan to intern local Japanese, supposedly to protect the home front and the defense industries from spies and saboteurs. His radio speech of January 29th mentioned the first part of the plan.

A few days ago, we dropped, at least temporarily, from the city payrolls all employees of Japanese parentage. This was done without violating the legal rights of anyone.

Not everyone approved. Clifford Clinton, of Clifton’s Cafeteria fame and one of the men behind Bowron’s election, wrote a letter of protest that reads, in part, "We should not permit hysteria and indignation to serve as a substitute for hard work and hard thinking. We should build up public morale by taking intelligent and humane action, not undermine it by yielding to the hysteria of a witch-hunt."

An unnamed Pasadena realtor also protested, writing, "Sometimes I wonder how genuine our democracy is. If by democracy we mean freedom and liberty for the white man, let’s say so and promptly subjugate all others so Hitler cannot divide and conquer. But it’s not that kind of America: let’s publicly reinstate these citizens."

But dissenting voices – and a report from the Office of Naval Intelligence -- were ignored. Bowron’s background as a judge was on full display as he defended the internment in his weekly radio address.

I have merely pointed out a legal theory that native-born Japanese never were citizens under a proper construction of the provisions of the United States Constitution. If they never were citizens, nothing could be taken from them and their position is different … (they) are in a class by themselves.

The theory he cited was a dissenting Supreme Court opinion from the 1890’s. He went on to express his preference that Los Angeles would never again have a large concentration of Japanese.

But many internees did return ...

It appears that within the next 3 months, 10,000 Japanese will be brought back to us from the relocation centers.

... and started up their lives all over again. A few reclaimed their homes and businesses, but most couldn’t.

The case for justifying the internment camps was never successfully proven. The U.S. Government no longer considered Southern California in danger from sabotage in mid-1943 and started to release the internees. The Supreme Court ruled against indefinite detention of U.S. citizens in December 1944. Six city employees were photographed with Mayor Bowron when they returned to city service in January of 1945.

Bowron was mayor of Los Angeles until 1953, and until Tom Bradley, was our longest serving mayor. After he left office, he became director of the Metropolitan Los Angeles History Project.

Fletcher Bowron died in 1968 at the age of 81, but before he did, he made several public apologies for the treatment of the Japanese citizens of Los Angeles.

Michael Holland first told this story in Alive!, the LA City employee newspaper.

The Japanese American National Museum in Little Tokyo will be marking the 75th anniversary Executive Order 9066 on Saturday, from 2-4p, with a Day of Remembrance.

Surf and turf wars: Co-founder of Surf Punks remembers localism battles of the 60s and 70s

Maybe you've been following the saga of the gang that controls surfing on Lunada Bay on the Palos Verdes Peninsula. After years of inaction, it looks like the gang will finally have its illegal beach fort demolished.

In 1976, a group called The Surf Punks captured the essence of surf localism with their songs "My Beach," "My Wave," and "Punchout at Malibu:"

Now that surfing's caught on

There's less waves to go around

I'm a fool to stay in town

A fool to stay in town

Now it's the goons in the water

That are bringing on a slaughter

Gonna be a punch out at Malibu

A punch out at Malibu

The co-founder of The Surf Punks is now in his 60s and lives in Oregon, in part because surfing here is "done."

He's Dennis Dragon, and he grew up immersed in the ocean off Malibu, and immersed in music: his dad was Hollywood Bowl Orchestra maestro Carmen Dragon, his mom was an opera singer, his brother and sister-in-law were The Captain and Tennille, and Dragon produced "Love Will Keep Us Together" and many more hits.

In fact, the hit records gave him the dough to set up the recording studio where he and Drew Steele made music.

I talked with Dragon about the scene in 1976; about Valleys, dummies, and shoulder hoppers; bird poop in your eye; and whether they made a difference. Listen to the audio for our in-depth conversation and lots of music.

RIP Formosa Cafe: Hollywood watering hole, creative touchstone for generations

The Formosa Cafe on Santa Monica Blvd had been in decline for a long time. The drinks and food were pretty universally reviled. It was run down. The feng shui was way off and weird. It had started to look and feel like one of those open air tourist bars on Hollywood Blvd.

But you didn't go there for the food or the drinks. You went there because the Formosa was woven into the fabric of Hollywood History. Or, as crime writer Denise Hamilton says, "when you're sitting in those red banquette booths and getting sloshed because everyone from Frank Sinatra's to Orson Welles' to Marilyn's fanny has warmed that exact leatherette and sipped from those exact highball glasses with the red maraschino cherry, and therein lies the magic."

But for the time being, you'll have to warm your fanny elsewhere, because the Formosa closed last week.

As Chris Nichols reports in LA Magazine, there is hope for a rehab:

“My goal is to find someone that wants to bring back the history,” said Gabe Kadosh, vice president of leasing firm Colliers International. “This is not going to turn into a Sharky’s or something." Kadosh has assembled a group of candidates who have rehabilitated historic buildings and crafted elaborate theme bars, including the Houston Brothers of La Descarga and No Vacancy, Jared Meisler and Sean MacPherson of the Pikey and Jones Hollywood, and Bobby Green, Dimitri Komarov and Dima Liberman of the 1933 Group, who recently restored the Highland Park Bowl and the Idle Hour. “Those are the kind of caliber of people I’m talking to,” said Kadosh. “They have a history and a nostalgic feel, and they can bring it back. I think these days people want an experience.”

But in the meantime, I met Denise outside the Formosa ...

... to talk about the Formosa's role as a cultural touchstone, a creative shortcut, and the inspiration so many have drawn from it ... like Curtis Hanson, who filmed this scene in "L.A. Confidential" there:

Denise says the Formosa was a Hollywood elite watering-hole, "Today if you want to see movie stars, they are cloistered away behind gates in Malibu or in restaurants where the hoi polloi can't get reservations." This is what made the Formosa so magical, she says. "The Formosa was one of these very old Hollywood eateries where it didn't cost a fortune, you didn't have to be famous to get in ... and you might see Cher, Bono, or Jack Nicholson."

The Formosa also appeared in the hit film musical "La La Land," with Emma Stone and Ryan Gosling, and Denise says "When you see that montage and you see the lit up neon sign. You don't have to say anything else. Everybody knows that is one of the quintessential, archetypal places."

Listen to the audio player for much more of our conversation.

Commentary: Rest In Peace Juan Gabriel, the greatest songwriter of his generation

Editor's note: Singer Juan Gabriel died Sunday at his home in Santa Monica. He was 66. KPCC education correspondent Adolfo Guzman-Lopez remembers the star for who he was: the greatest songwriter of his generation.

As we begin to unpack the meaning of Juan Gabriel's life and work, I’m reminded of all the things Juan Gabriel was: songwriter, singer, queer icon, borderlands product, and a very proud Mexican. Here, he musicalizes a tribute speech to the great singer Lola Beltan:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yAHac9GqaP0

"Long live your music, your freedom, your sky, your earth, your sea, your sun, your moon, and all your stars." Then Juan Gabriel sings the refrain “Que Viva Mexico” 11 times.

Juan Gabriel was a craftsman, like Carole King or Paul Williams.

He had a deep knowledge of the ranchera and mariachi formulas, enough to twist the lyrics and marry them to the music to the point where no other arrangement seemed right, like the popular Broadway lyricists.

Here’s a good example, "Tu a mi ya no me interesas," which means "you don’t interest me anymore."

It's one of my favorites, sung by one of Mexico's greatest ranchera singers, Lucha Villa — just one example of how many of Mexico's great singers covered Juan Gabriel’s songs:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Nvm2XyAL_p4

"I want you to understand, what I'm about to tell you, and I hope you understand me, that I don't mean to hurt you, It turns out I don't love you anymore, Don't ask why, Even I don't understand, but believe me it's the truth, Why? Don't know, I don't know why you don't interest me anymore..."

Back in the mid 1970’s, my mom and I traveled a lot between San Diego and Tijuana. We spent a lot of time in music-filled Tijuana taxis and buses late at night. Those were good years for my mom and me. She was happy and we listened to songs like "No Tengo Dinero" and "El Noa Noa," which was named after a nightclub from Juan Gabriel's early years. Today, they bring those good times back.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=om_NAcmskKs

I'm remembering a particular moment in a Tijuana bus at night with my mom. I couldn't have been more than 6 years old. As ballads kept coming out of the radio, I remember thinking: "Juan Gabriel, Julio Iglesias, Lucha Villa ... love, love, love."

"Why does everybody keep singing about love? Why are all the songs about love?" I asked my mom.

"That's the most important thing to sing about," she said.

And Juan Gabriel was one of the best at it.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KwvJDe0zMBU

How Leon Russell helped me meet my mom

Off-Ramp intern Rosalie Atkinson on the death of Leon Russell and his place in her life. Russell died Sunday at 74.

I'm a teenager. It's five o'clock and a glow from kitchen lights is spilling out the open front door, guiding my feet up the 4 stairs into my childhood home. Like most nights, I enter to find my mom, Tanya, dancing in front of the stove.

"Stranger in a strange land! Whoaaa-ooooh!" She sings at me, squinting, spinning around our kitchen.

She points at me and I join in. Together we sing, "Stranger in a strange land!" as I dip a finger into a pot of pasta sauce, a cloud of garlic and tomato sauce harmonizing alongside us.

I don't reflect on these moments much because nothing's changed: I know if I were to walk in the door somewhere around dinner time, I'd still find her singing these love songs to her pots and pans. But with the death of musician, songwriter, and fixture in our lives, Leon Russell, I'm forced to issue a letter of gratitude for what his music did to my life.

On Sunday night, in his Nashville home, Leon joined Heaven's band peacefully in his sleep. A member of session musician collective "The Wrecking Crew," Russell quietly tied together albums of the heavy-hitters in American music history: Bob Dylan, George Harrison, B.B. King, Herb Alpert, and so many more. His first commercial success came after writing "Delta Lady," popularized on Joe Cocker's 1969 self-titled album. From then, Russell's songs went on to be performed by the Carpenters, Willie Nelson, the Temptations, and Amy Winehouse.

He was a proud cornerstone of the Nashville music scene, and Leon's experiences in music transcended racial barriers. His music danced across rock, blues, country, pop, and gospel. This versatility helped him build his entirely unique sound; not afraid to bellow crushing minor notes, or screech out twangy ballads through quivering vocal chords. This is the sound wafting through the background of my childhood and memories of my mom that make those moments so important to me now.

Leon Russell was different, unclean, unencumbered by success, unlike so many highly decorated, popular artists. I can remember sitting at the dinner table, tracing the outline of his gray top hat on the cover of Leon Live, watching my mom.

Last summer, I saw Leon perform in Oakland with my mom. We squished into a tiny table at the end of his giant, white grand piano, and watched him as he used his cane to meander to his bench. Without looking at the keys, his hands found their place, his voice found amplication, and my mom and I found joy.

I can still see it today: During Leon's biggest hit "A Song for You," I turn to my mother and I mouth the words, "I love you in a place, where there's no space or time. I love you for my life, you are a friend of mine."

A Song for You (1971) by Leon Russell

After the concert, we hang around the stage door. Eventually, Russell and his entourage emerge and mingle with fans. Many drunken baby-boomer's asking him about working with Elton John, asking to try on his stark white cowboy hat, ambition strikes me and I push through them, with my ticket in one hand and my mom's hand in the other, and I manage to get some important words out:

"Leon, my mom is a huge fan and she played your music for me growing up and now I am a big fan too. Will you sign our tickets?"

Almost animatronic in his movements, he looks at me, and he looks at my mom, then says, "Well gee, I appreciate that. I'll sign 'em right now. You got a camera? Let's take a photo."

Without Leon Russell's music, I wonder if I'd ever have really met my mom.

Before my mom had my brother and me, and she got the moniker "mom," there was a woman who loved vinyl records, who loved Southern rock, and who deeply loved Leon Russell. He introduced me to her spirit and allowed me to share something meaningful with her, besides genetics. He shared with me the woman that slept dormant in her, to be awakened by the sentimentality of a certain album or vocal twang.

For these reasons and more, I will miss you, Leon Russell. But I will always thank you more.