You shouldn't modify the word “unique,” but if you could, you could say that singer Baby Dee is one of the most unique performers you’ll ever encounter ... The Day-Lee Foods World Gyoza Eating Championship ... Rabe wades into the LA County Arboretum's Baldwin Lake, which is in big trouble ... Film historian R-H Greene takes a new look at a long neglected late film by Orson Wellles, “Chimes at Midnight,” now in the Criterion DVD collection.

You haven't got a box big enough for singer Baby Dee

Since Baby Dee was born in Cleveland in 1953, she's been a tree surgeon, a church organist, and a street performer - she used to play her harp while riding on a custom built tricycle. She didn't make the first of her eight albums until she was almost fifty, and she's helped launch successful careers for several of her collaborators while avoiding mainstream fame and fortune herself. In her music, you can hear ancient church music, Weill and Brecht, silly raucous drinking songs... and beauty, heartbreak, and longing.

There are a lot of other interesting things about Baby Dee, who opens for Swans at the Fonda Theatre Friday, Sept. 2. But you can Google them. In our interview, I wanted to get at the heart of her music:

How did growing up in Cleveland proper, not the suburbs, affect your music?

I grew up in the sort of nice/ugly part of Cleveland. The West Side, steel mill side of Cleveland. And not in the suburbs. It would have had a huge effect on my life. Because the street life where I grew up was really very rich and vivid. It had a huge effect on me. I think it had a lot to do with why I became a street musician for a while. I just like the idea that wonderful things can happen on the street with just regular people, with strangers. I fell in love with that idea as a child.

How did being a street performer for so many years shape how you perform and make records now?

The street thing turned me into a bit of a carny. I became a little bit rough around the edges, sort of show-bizzy scruffy bargain-basement way. That's still kind of in there somewhere.

When I did my act I never stood in one place. I don't like to think of people walking by. I don't do that. My act was very mobile and I used to go after them. I would target people and then like dive-bomb them with a stupid song and get a couple bucks out of them. But I had a kind of breakdown slash epiphany and then I changed. I was a church organist for many years and I liked the quietude of that, and so my life has been one of real extremes.

What music were you hearing as a little kid in Cleveland?

As a little kid, my grandmother used to play the piano. All these old ballads like "Too-Ra-Loo-Ra-Loo-Ra," "This is the Army Mr. Jones," all these old chestnuts. Not that I so much admired them, but there was something in the forms of them that I took on. But I didn't even admit to being influenced by that stuff until pretty far out. I kept that secret.

I guess everybody's embarrassed by their homey little stuff. But there's stuff in there I don't like. All those great American songwriters that everybody loves, I kinda don't. It's just terrible but I'm not crazy about those things. The sappy, sentimental songs, like Irving Berlin? I can't stand anything Irving Berlin wrote.

What's the story behind "The Earlie King?"

The Erlkönig (Early King) was a poem by Goethe, the great German poet. It's an old story, a legend, and the story is that he's a being who seduces small children to their death. He comes and he steals their life away. It's really horrible. Really spooky.

Who rides so late through night and wind?

It is the father with his child.

He has the little one well in the arm

He holds him secure, he holds him warm.

"My son, why hide your face in fear?"

"See you not, Father, the Erlking?

The Erlking with crown and flowing cloak?"

"My son, it is a wisp of fog."

There was an untimely death in my family before I was born. My parents lost a child, and it made my father a little crazy but in ways he didn't realize. So it came up in our piano lessons that we had to play this song (set to music by Schubert) and my father became fascinated with it, without realizing this song was basically about him and this experience of losing a child. And he always wanted me to play it for him.

But of course as a child I knew what was going on, so it was a very strange thing - the child playing the creepy death song for the father, the father who's oblivious. That's what my song is about.

Daddy, can you hear me?

It's got so hard to speak.

I'll kiss your bristly cheek

and go with the Earlie King.

Up from the table,

my brother's tiny soul

all gone, swallowed whole,

taken by the Earlie King.

-- Baby Dee's "The Earlie King"

For much more with Baby Dee, including her infectious laugh, why she moved to The Netherlands, and how to say the name of her town like a real Dutch person... use the audio player above to listen to my in-depth interview.

Bringing back the Arboretum's sludge-filled Baldwin Lake

In its best years, the LA County Arboretum and Botanic Garden's Baldwin Lake was a gem. It ran 12 to 15 feet deep and served as a prime filming location for decades—if you've seen "Marathon Man," "Fantasy Island" or 1932's "Tarzan the Ape Man," you've seen the Arboretum on the silver screen.

But if Tarzan and Jane tried to swim in Baldwin Lake today, they'd get slimed. Errol Flynn and his men in "Objective: Burma!" would lose to the Axis. And "The Creature from the Black Lagoon" would flail around for a few seconds, toppled over, and be savaged by carp.

I put on waders and tramped out as far as I could before my feet started getting stuck in deep, non-toxic muck. It felt like I was wearing concrete overshoes.

If the lake was healthy, that would never have happened. But Schulhof says the lake is now down to an average depth of 30 inches, and suitable only for the carp that thrive there with the dozens of abandoned pet turtles.

The lake is filling up from the bottom with sediment and because of the drought, it's also drying out from the top.

It wasn't actually all that healthy before the drought - the sediment has been building since the 1950s - but as you can see in this old "Visiting with Huell Howser" video, it least it looked good when the rains kept it full.

Visiting with Huell Howser at the Arboretum

Baldwin Lake is named for EJ "Lucky" Baldwin, who owned the land - the Baldwin Ranch - the Arboretum stands on. He built the lake in the 1800s. His great great great granddaughter Margaux Viera is a member of the Arboretum board and a member of the Save Baldwin Lake Task Force, which is raising money and awareness.

"It's extremely important," she says, to restore the lake. "A lot of my family members are not alive anymore, and we feel it is our purpose to help preserve and conserve what Lucky Baldwin created here, and the lake was his crowning jewel. Without this lake being restored, the Arboretum cannot possibly be what it was meant to be."

But it's a huge task, and an expensive one. Viera won't even venture a guess at the total cost.

The Arboretum is making the case that the lake is important not just to the Arboretum, but to the health of the surrounding environment. "For this part of the San Gabriel Valley, the Raymond Basin aquifer has been an essential resource for centuries," says Schulhof, the Arboretum's CEO.

"Now, the lake is the collection basin for 155 acres of suburban Los Angeles. So this lake becomes an important part of the larger watershed."

Under one plan, storm runoff from those neighborhoods would run through a filtering wetland at the park, then - much cleaner - into the lake, which could recharge the aquifer. But first, the lake would have been dredged of its sediment.

It won't be cheap, and it'll take a while. Schulhof he expects to fund the restoration through a combination of government funding and donations from the public. After all the studies are done, Viera says the actual physical work of restoring the lake could take five years.

The good news: Schulhof says testing shows the sludge is safe to use as a rich fertilizer on the grounds of the arboretum. "But our immediate task is to get a grant from the state water board and hire the engineers who can determine the best course of action."

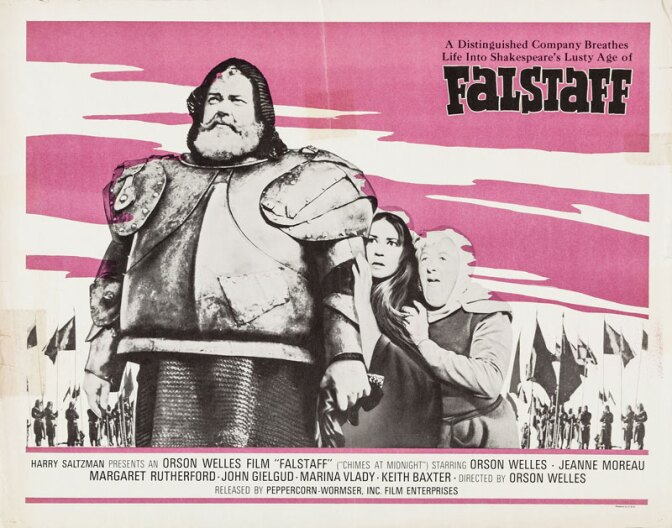

With Blu-Ray release of "Chimes at Midnight," it's time to re-evaluate Orson Welles' legacy

In 1962, Orson Welles gave an interview to the CBC in Paris. One question brought him up short.

Interviewer: Does the word "home" mean anything to you?

Welles: Oh yes...

Interviewer: And when you think of it, where do you think of it?

Welles: Now that's a problem...

Interviewer: No such thing for you?

Welles: No.

"Home" had ceased to be a clear concept for Welles 14 years earlier, when he left the US at the start of the McCarthy era and established himself in Europe. He directed six films there. All were fascinating. Each went all but unseen in America. And so a myth took hold: Welles the washout, who peaked at age 25 with "Citizen Kane," and never lived up to his promise.

Two new Criterion Blu-Rays demonstrate the depth of Welles' European achievement. "Chimes at Midnight" and "The Immortal Story" were the last two narrative films Welles completed as a director.

Welles made "The Immortal Story" in 1968. It's a haunted fairytale about the creative process adapted from a story by Isak Dinesen. Notable for its painterly compositions and uncharacteristically static camerawork, "The Immortal Story" is Welles' only completed film with a sex scene in it. It's also his only narrative shot entirely in color.

If "The Immortal Story" is a chamber piece, 1965's "Chimes at Midnight" is an opera.

A remarkable Shakespearean mashup, "Chimes" is an epic summation of Welles the artist on a canvas as broad and alive as "Citizen Kane." Welles was originally a theater prodigy. As a schoolboy, he co-authored a series of Shakespeare books that became standard schoolroom texts. Welles adored Shakespeare, but he didn't revere him. On stage or onscreen, he attacked Shakespeare's plays, tearing them apart line by line, then reassembling them for new purposes.

"Chimes at Midnight" combines the two "Henry IV" plays, "The Merry Wives of Windsor," "Richard II," "Henry V" and passages from Holinshed's "Chronicles" into a new tragedy, centered on a comic character: Sir John Falstaff, a role Welles was born to play: a pleasure seeking force of nature who mentors an English crown prince in the ways of hedonism.

In an extra on the DVD, Welles' Prince Hal, Keith Baxter, explains the deep psychic links between Falstaff and Welles: " The similarity between Falstaff and Orson Welles--not just the physical appearance, the greediness, the loving of food and wine. But more than that. He was always looking for a buck. He had to duck and dive. And I think the identification was peerlessly exact."

"Chimes" is Welles' most confidently directed film. In its celebrated central sequence, a long and horrific battle scene begins with the pomp of mounted heraldry and ends in mounds of men, bleeding into battlefield mud. Welles does something here that isn't in the original source material. He deconstructs the myth of heroic violence.

John Gielgud -- a great stage actor mostly ill-served by movies -- play's Prince Hal's long-suffering father, the doomed usurper Henry IV. When Gielgud recites the tormented king's most famous monologue ("Uneasy lies the head that wears a crown..."), Welles -- a king of camera movement -- simply holds his actor in a perfectly composed profile, and lets him speak. Geilgud's Henry IV is quite possibly the finest Shakespearean performance ever committed to film. But it's Welles -- a far more problematic actor in other contexts -- who gives "Chimes" its beating heart.

Welles was the son of an alcoholic father, who like Falstaff, introduced his brilliant child to a worldliness beyond his years. Like Falstaff, Welles' father was rejected by his son because he had to be. And like Falstaff, Richard Welles died before he and the boy who loved him could make amends. Late in life, Welles wrote an article about his dad for Paris Vogue. In it, he unfairly says he "killed" his father by rejecting him.

On Criterion's Blu-Ray, experts and eyewitnesses including actor and Welles biographer Simon Callow strive to describe the devastating impact of Falstaff's wrenching close-up when Hal shuns him. "There is something quite extraordinary in Welles performance at that moment," says Simon Callow, actor and Welles biographer. "He expresses something so unexpected! Which I'm not sure I even understand, but I acknowledge its authenticity completely. Which is that when Hal banished him, Falstaff is suffused with a kind of loving admiration of him. As if to say, `That's my creation. I taught him to be a man, I taught him to be a king. And he was in tears, himself."

Was Welles grieving his father here? Was he forgiving himself? Is this the drunken Richard Welles acknowledging his son's call to glory? This one moving and mysterious close-up affirms Welles' greatness as auteur and actor. If you subscribe to view of Welles as essentially a tragic artist, "Chimes at Midnight" isn't just a consequential Welles film. It's the essential one.

Song of the week "Feel You" by Julia Holter

This week’s Off-Ramp Song of the Week is singer/songwriter Julia Holter's “Feel You,” from her 2015 album Have You in My Wilderness.

Holter is an LA native and a graduate of Cal Arts, with four albums to her name so far.

What’s she been up to lately?

She composed the score for the upcoming movie “Bleed For This,” executive produced by Martin Scorsese and staring Miles Teller. She’s playing FYF Fest this Sunday in Exposition Park. And she talked about her music on KPCC's The Frame on Friday.

What it takes to win Little Tokyo's annual Gyoza eating contest

For the past 10 years, professional eaters have gathered in downtown Los Angeles' Little Tokyo to stuff their faces full of Gyoza.

It's the Day-Lee World Gyoza Eating Championship — a contest held near the end of Nisei Week in Little Tokyo where professional and amateur eaters are invited to eat as many pork and cabbage stuffed potstickers as they can.

It's also the site of a world record: It belongs to Joey Chestnut, called "the greatest eater in history" by Major League Eating. In 2014, the California native ate 384 gyoza in just 10 minutes.

This year, things kicked off with an amateur competition open to locals. Christian Miyamae took first place in one of the contests, eating 34 gyoza in 2 minutes.

For his victory, contest organizers sent Christian home with a 12 pack of beer — Sapporo, of course. Members of the Los Angeles police and fire departments faced off, too — firefighters beat-out the LAPD: 170 to 145.

But how did the professionals stack up?

Major League Eating’s Matt Stonie returned to Little Tokyo to reclaim his 2015 title.

“I’m sweating right now," Stonie said "It’s hot out here today. It’s a 10 minute sprint up there."

He won $5,000 and a trophy for eating the most once again — 323 gyoza.

Want to try it yourself? Eat hundreds of Gyoza at your own risk, but here's a tip: Stonie says the best way to stuff yourself is to use gravity to your advantage by jumping up and down.

When the contest returns next summer, maybe you can be a gyoza eating champion, too.

Review: Huntington's 'Blast' is the backstory to Getty's 'London Calling'

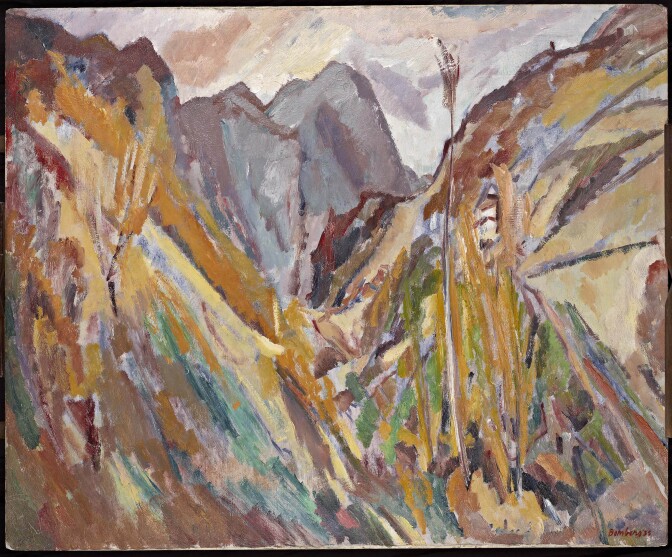

Off-Ramp commentator Marc Haefele reviews "Blast! Modernist Painting in Britain, 1900-1940," at the Huntington Gallery through November 12. "London Calling" is at the Getty Center through November 13.

In England in the decade after World War 2, a third of the housing was bombed out; shops were empty. Food and even clothing were tightly rationed. As the old Empire vanished into thin air, the nation hovered on the edge of economic collapse. But from this stressed, sad, grayed-out culture came an unprecedented outpouring of great art.

The Getty Museum just opened a new exhibit called “London Calling,” featuring six artists from England’s post war era. And across the county, the Huntington has a new show called “Blast," which showcases a dozen pictures by predecessors, mentors, and teachers of those six “London” artists.

The Getty’s display offers more spectacle, and of course it includes Freud and Bacon, the two most famous British artists of our time. On the Getty’s streetlight posters you see Lucien Freud’s “Girl with a Kitten”— the cat somehow content in a stranglehold, the girl’s attention diverted into the middle distance. The geometry is loose, but Freud’s attention to detail is achingly fastidious. 10 years later, these aspects reverse—Freud’s fussiness is now a studied blotchiness, the shapes more massive and real, as he reaches toward the incredible physicality and presence of his last great nudes.

Francis Bacon spoke of his art as “sensation without the boredom of its conveyance,” and many think he intended to shock and appall. The Bacons at the Getty are relatively sedate, stressing his mighty shaping technique, his figurative genius, his startling color sense.

There’s also R. B. Kitaj, who’s been called the greatest historical painter of our time. He’s almost blissfully figurative with his wedding, his refugees; his tributes to the murdered Rosa Luxemburg and Isaac Babel riding with the Red Cavalry; something like Chagall if he’d apprenticed with Breughel.

Frank Auerbach and Leon Kossoff -- still painting today in their 80s and 90s – are more expressionist, but still invoke the plain, battered surroundings of a weary metropolis. And Michael Andrews wrapped up his short career with pure landscape, pictures literally infused with the sand and dirt in his paintings.

Go see “London Calling” at the Getty first, then head to the Huntington, to see a dozen recently acquired or loaned prime British paintings from before World War 2, some of which strongly influenced the Getty painters.

There’s pioneering modernist David Bomberg, with whom both Auerbach and Kossoff studied. You can see in their work Bomberg’s bold use of layered paint and colors, and a leaning toward abstraction.

There’s Stanley Spencer, whose powerfully emotional work with its combining of plants, humans, and animals foreshadowed themes of Lucien Freud.

Walter Richard Sickert is represented by one of his placidly unsettling "ennui" studies. He’s the Godfather of most modern English painting, and in his later years revised his style in keeping with the younger generation he sometimes mentored.

There is the sardonic "Cubist Museum" of Wyndham Lewis, who carried the avant garde torch in British painting until he lost faith in modernism and found equal fame as a novelist.

And there’s a fine, subtle portrait by Gwen John, the only woman painter in either of these shows.

It’s 28 miles from the Getty to the Huntington, but you should make the trip to see “London Calling” and “Blast.” Together, they provide a rich, continuous century’s span of English figurative art we’ve seldom seen here.