This story is free to read because readers choose to support LAist. If you find value in independent local reporting, make a donation to power our newsroom today.

This archival content was originally written for and published on KPCC.org. Keep in mind that links and images may no longer work — and references may be outdated.

LA County's probation seeks to change how juveniles transition from detention to home

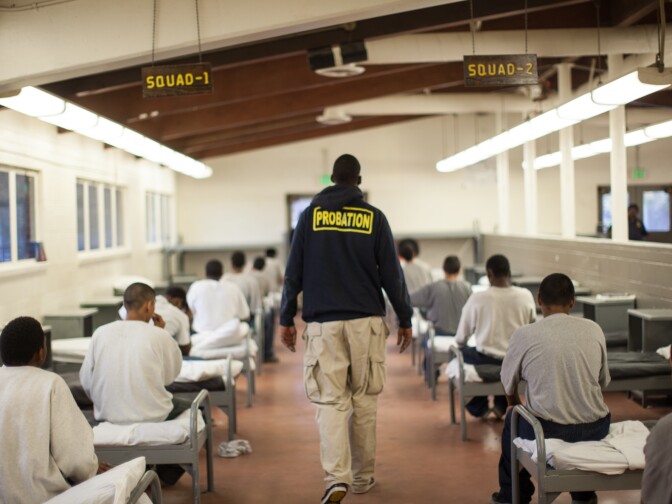

Camp Afflerbaugh’s main dormitory is a sprawl of metal beds, each one with a teenage boy sitting or bouncing. Damian, a tall and skinny 16-year-old, is resting on a bunk in the back corner. The kids are lining up for school when a large, uniformed man yells out a command. Every boy in the room instantly jumps into bed.

“He told us to 'go flat.'” Damian says. "Every day they give us commands to line it up, go flat, or to relax.”

Juvenile camp is a regimented environment — different from a lot of these kids’ homes. Going to school, regular counseling, and visits to the doctor are the norm. Damian is here because he brought an unloaded gun to his high school in Pomona. He says there was tension between two groups at school.

“I was like, 'I’m tired of this,'” Damian says. "You know, they think they’re all bad just because they’re rich and all. I’m just going to take my gun and put a scare into them."

School administrators found the gun, and Damian was sent to camp. He's adjusted well, with a practically spotless disciplinary record. L.A.’s Deputy Probation Chief Felicia Cotton says even when kids are successful in camp, once they go home, they often fall back to old behaviors.

“You’ll hear many people, and even parents that come to us and say, 'hey take this kid and when we get him back, he’s going to be perfect,'” Cotton says. "Camp is not a cure-all.”

This belief – that camp is of limited value – is a cultural shift that’s growing inside L.A. County’s Probation Department. Now, Cotton says, camp is seen more as an intervention that momentarily plucks a kid from their ecosystem and tries to give them the skills to deal with whatever caused the behavior that led to detention.

“Because the real rehabilitation comes when they get in their natural ecology," Cotton says.

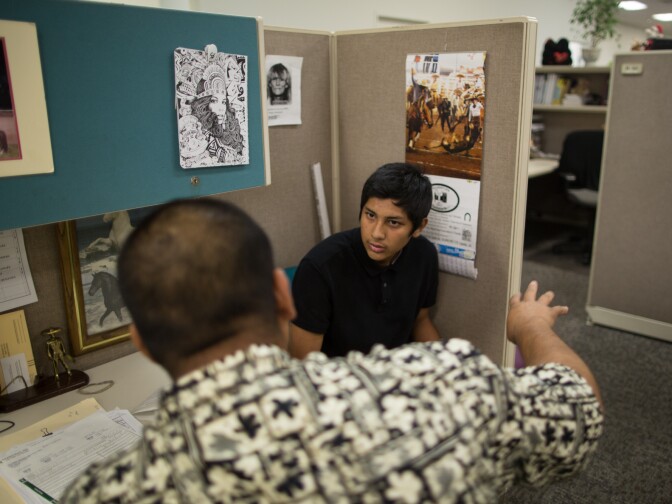

Under a policy change being implemented over the past few months, more and more attention goes into planning for life back in the community. Each child leaving camp now has a team to plan his or her transition.

Damian's team meets about two months before his release date. His probation officer is there. So are representatives from L.A.’s mental health department and county schools.

Damian’s mom, Martha, is also there. Her main concern for Damian is clear.

"He needs to go back to school," she says.

School is one of the tricky pieces of the puzzle for Damian, as it is for a lot of kids leaving camp. Whether stigma or safety concerns, most public schools don’t want students who are on probation.

The team decides Damian should try reenrolling in his old school, where he was expelled from. They also decide to send a therapist to his home, and possibly a tutor, as well as help Damian find a job. Martha, who says she waits all week for the weekend so she can visit the camp, is just ready for him to be home.

"I always tell him, 'Damian, I never cut the umbilical cord from me to you,'”she says. "He’s my baby."

A few days after Damian leaves Camp Afflerbaugh, he says he’s still adjusting from camp life.

"I couldn’t go to sleep," Damian says. "I don’t know why. I guess it’s because I didn’t want to go to sleep and wake up still in camp, you know?"

It’s his second day of school at Pomona SEA, a continuation high school that takes a lot of kids coming out of juvenile camps. Damian’s old school wouldn’t let him back in. He says he doesn’t miss it.

“It’s just people causing unnecessary drama," Damian says. "People gossiping.”

Pulling up to the new school, Martha pops out of the vehicle to talk to the school administrator. She'll return to the school three different times to take her son to various appointments. On one such run, she's driving Damian to a job interview at Subway. Martha tells her son she’s considering quitting her job to be with him full-time.

Damian doesn't want to hear it.

"That’s stupid," he says "If you do that, I’ll really be mad at you."

It's a few weeks later and Damian goes to court for his first meeting with a judge since being released from the camp. He and Martha are uncharacteristically quiet when they arrive at the courthouse. When they come out, they’re both grinning.

"It went good," Damian says. "The judge said she didn’t want to see me until next year."

If he doesn’t have any problems, he’ll be released from probation early.

"I’m not going to have a problem," Damian says.

Nobody’s really sure what happens next. If all goes well, 2014 will be the year the juvenile justice system slowly pulls out of the lives of Damian and his family.

It is KPCC's policy not to publish the names of juveniles arrested for crimes, unless they are prosecuted as adults. KPCC has agreed not to use the last names of Damian and Martha for this story.