This story is free to read because readers choose to support LAist. If you find value in independent local reporting, make a donation to power our newsroom today.

This archival content was originally written for and published on KPCC.org. Keep in mind that links and images may no longer work — and references may be outdated.

Have SoCal's water supplies recovered? Depends on where you live

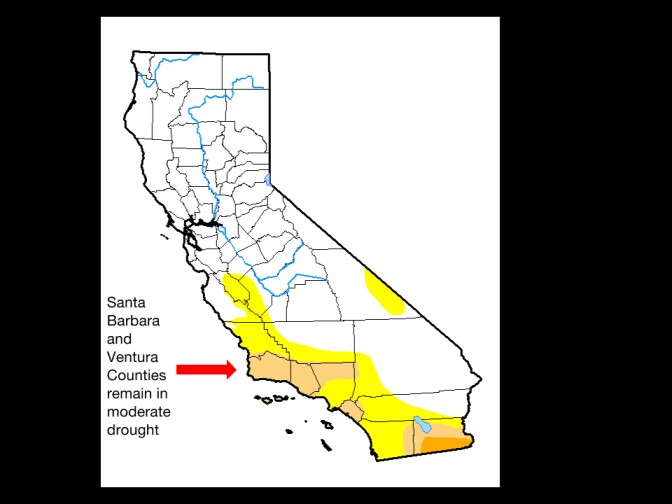

Update: Gov. Jerry Brown lifted the drought emergency for most of California on April 7.

Here in California, we've been on a roller coaster when it comes to water. After five years of crippling drought, the Golden State had one of its wettest winters on record. So what has all the rain and snow meant for our water supply in Southern California? It depends on where you live and where your water comes from.

Imported water

About thirty percent of Southern California's water comes from far, far away: Lake Oroville, a giant reservoir in the Sierra Nevada about 80 miles north of Sacramento.

It travels here through the State Water Project, an approximately 700-mile long series of canals, pumps and pipelines that begin at Lake Oroville and end in various reservoirs throughout Southern California.

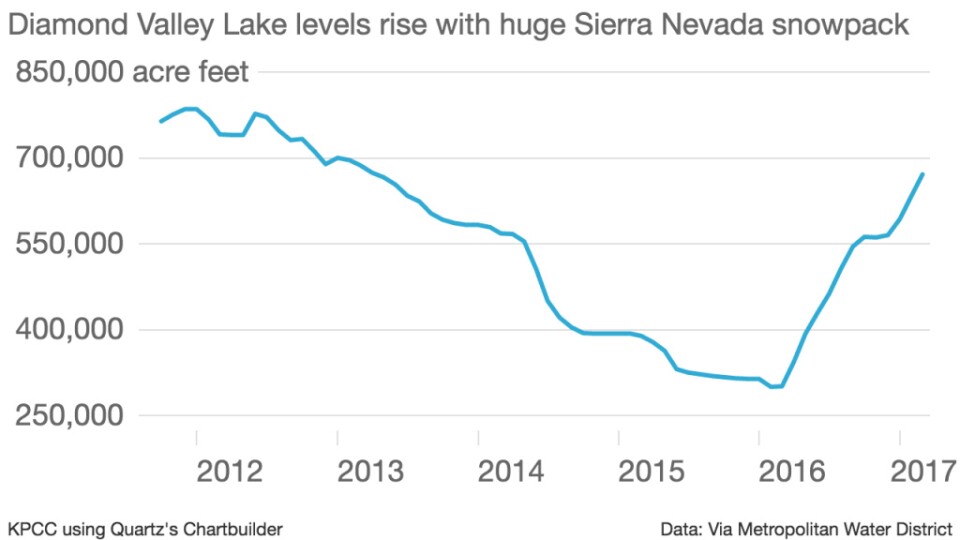

The largest of those is Riverside County's Diamond Valley Lake. It holds enough to supply 400,000 families for a year.

It's an odd lake – it gets hardly any water from surrounding streams, and is almost entirely fed by imported Sierra Nevada water. That means the amount of water in the lake is much more dependent on Sierra snowpack than how much it rains in Riverside County.

During the worst of the drought, water levels in Diamond Valley Lake dropped precipitously. The California Department of Water Resources almost completely turned off the spigot of the State Water Project, delivering just five percent of what water agencies, like the Metropolitan Water District, which operates Diamond Valley Lake, requested. But then, it started raining and snowing in the Sierra Nevada this winter, and the lake bounced back. In the last year, the amount of water in Diamond Valley Lake has doubled.

Metropolitan also gets water from the Colorado River. Because of the wet winter in the Rocky Mountains, water supplies there are looking better than they have in the past three years. The city of Los Angeles has its own aqueduct that taps the Owens River watershed in the eastern Sierra Nevada. The city expects to get nearly 80 percent of its water from the aqueduct this year – three times as much as last year.

Diamond Valley Lake is pictured in satellite photos from March 2016 and 2017. The lake doubled in volume in that time. (Credit: Lakepedia)

Groundwater

Many communities in Southern California supplement imported water by tapping local aquifers. At nearly 170 square miles, the Main San Gabriel Groundwater Basin, which supplies drinking water to 2.2 million people in the San Gabriel Valley, is one of the largest.

The basin is like a large, underground river that flows from the mountains down to the Puente Hills. Perforated wells tap into water-saturated gravel and sand.

During the drought, groundwater levels in the basin fell to their lowest level ever in October 2016. And they haven't bounced back yet – the basin is up just 11 feet from its low point.

That's surprising, given how much it rained this winter in Southern California – it was the wettest since 2005. Tony Zampiello, the head of the Main San Gabriel Basin Watermaster, says it's because the watershed is so dry. The San Gabriel Mountains are acting like a sponge, soaking up rain and snowmelt before it can run downstream and percolate into the groundwater.

"When it first started raining, I started to sleep. And then when I saw how little we were getting, I went back to insomnia again," Zampiello said, taking a big swig of coffee.

It's not just groundwater – local reservoirs around Southern California are still recovering from the drought.

Surface water

Lake Casitas is one of those reservoirs. Tucked into the Ventura County's hills, the lake supplies water to residents of Ventura and Ojai, as well as many farmers and rural residents.

Unlike Diamond Valley, Casitas is fed solely by local streams and rivers. And it's been hurting in the drought. The lake is at just 44 percent capacity, even after winter rains raised the lake level by 15 feet. That's because this little patch of California is still in drought.

Cities like Ventura and Ojai rely entirely on local supplies of water like Lake Casitas. They can't sip from the Sierra Nevada water that flows through the State Water Project the way so many other Southern California cities can. And that makes them vulnerable.

Ron Merckling, resource manager with the Casitas Municipal Water District, worries that all the news coverage of the near record snowpack in the Sierra Nevada is sending the wrong message to his customers, who he says need to keep saving water.

"It's our job, our mission, to make sure we do not run out of water," he said. "That cannot happen. That is not an option."

Santa Barbara County is also considered to still be in drought, albeit a "moderate" one. The city of Santa Barbara continues to be squeezed by the water deficit because it relies largely on the Lake Cachuma reservoir for its water supply. The lake is about 35 feet below capacity. Residents of Santa Barbara are still required to use 30 percent less water than before the drought.

Lake Casitas in Ventura County is pictured in satellite photos from March 2016 and March 2017. The reservoir relies exclusively on rainfall to fill it. Ventura County saw above average rain this winter, but Lake Casitas is still only at 44 percent capacity. (Credit: Lakepedia)

What's next?

California just followed the worst drought in state history with one of the wettest years on record. Some water supplies have rebounded, but others are still very stressed. Water managers want their customers to know: it's no longer a drought emergency, but it's also not a water free for all.

"If you can live without the water in the last five years, then there's no reason why you can't live without that much water going forward," said Tony Zampiello.

He said psychologically, coming out of a drought is like ending a diet.

"Everybody kind of feels like [they] deserve a little extra dessert or whatever, but you can't do it."

That's why he doesn't even like the word "drought." To him, it enables an unhealthy cycle of cutting way back on water use, then bingeing as soon as it starts to to rain. Instead, he says what's needed is a healthy lifestyle in synch with the limits of the region's Mediterranean climate. He calls it the California way of life.

Special coverage: 'Drought to deluge'

This story is part of a full day of special coverage examining what the wet winter has meant for our water supply. Check out the full coverage Monday, April 3 on...

Morning Edition: While a healthy snowpack will be good for imported water sources to Southern California, that’s not necessarily the case for local sources of water. Reporter Emily Guerin explains.

Take Two: Host A Martinez talks to state and local water experts about the lessons we’ve learned from the recent cycle of dry to wet and what that means for how we manage water going forward.

AirTalk: Host Larry Mantle takes listener calls on whether the wet winter has caused you to rethink water conservation.

All Things Considered: Host Nick Roman takes a look at how the sudden change from parched to lush backcountry has affected local wildlife and habitat.